Scientists found rare isotopes that hint Earth was once struck by a stellar explosion.

An extraordinary new study suggests that a dying star may have exploded near Earth roughly 10 million years ago—and that our planet still bears the traces of its blast. Published in Nature Astronomy, the research analyzed deep-sea sediments containing rare radioactive isotopes that likely came from a nearby supernova. Scientists say the discovery offers new evidence that Earth has been touched by cosmic forces powerful enough to alter its atmosphere—and perhaps even its evolutionary history.

1. Clues Were Found in Deep Ocean Sediments

Researchers discovered traces of an isotope called iron-60 in ocean crust samples drilled from the Pacific and Indian Oceans. This radioactive element doesn’t form naturally on Earth—it’s produced in supernovae, the explosive deaths of massive stars.

Because iron-60 decays relatively quickly, its presence on our planet means the debris must have arrived within the last 10 million years. The samples act like a cosmic fingerprint, preserving a record of an ancient stellar event.

2. Iron-60 Is the “Smoking Gun” of a Supernova

Scientists consider iron-60 the telltale signature of a nearby supernova. The isotope forms when a star runs out of fuel and collapses, unleashing a blast so intense that it forges new elements and ejects them into space.

Previous detections of iron-60 in seafloor crusts hinted at at least two separate cosmic events. The new findings strengthen the case that one of those explosions happened close enough to dust Earth with its radioactive ash.

3. The Supernova Likely Occurred About 10 Million Years Ago

By comparing isotope decay rates and sediment depth, researchers dated the event to around 10 million years ago. That’s relatively recent in astronomical terms—well after the extinction of the dinosaurs but before modern humans evolved.

The blast likely occurred about 150 light-years away, close enough for particles to reach Earth’s atmosphere but far enough to avoid catastrophic damage. Still, such a nearby explosion would have showered the planet with cosmic radiation for thousands of years.

4. The Explosion May Have Affected Earth’s Climate

Some scientists suspect that radiation from the supernova could have influenced atmospheric chemistry. Increased ionization in the upper atmosphere might have thinned the ozone layer or altered cloud formation patterns.

While evidence remains circumstantial, the timing coincides with known cooling periods and ecological shifts in the Miocene epoch. It’s possible that the blast subtly reshaped Earth’s climate, ecosystems, and even rates of mutation among species.

5. Cosmic Dust from the Blast Still Falls to Earth

Even millions of years later, researchers believe faint traces of the supernova’s debris continue to drift into the solar system. Tiny iron-60 particles have been found not only in ocean sediments but also in Antarctic snow and lunar soil.

This steady “cosmic drizzle” supports the idea that Earth is still passing through the outer edges of the blast wave—a silent reminder of an ancient cosmic encounter that continues to leave its mark.

6. The Source May Have Been a Star in the Scorpius-Centaurus Association

Astrophysicists have pinpointed a likely source region known as the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association, a cluster of young, massive stars about 400 light-years away. Several of its members would have gone supernova around the right time.

Computer simulations of stellar evolution show that at least one of those dying giants could have been close enough to Earth to deliver the isotopic signature scientists now see in sediments.

7. Earth Was Likely Exposed to a Cosmic Ray Surge

A supernova releases enormous quantities of cosmic rays—high-energy particles that can penetrate planetary atmospheres. When those rays reach Earth, they can increase radiation exposure and trigger chemical reactions in the stratosphere.

Models suggest that such a wave of radiation may have lasted for thousands of years, possibly influencing genetic evolution by slightly increasing mutation rates across species. However, scientists emphasize there’s no evidence of a mass extinction linked to the event.

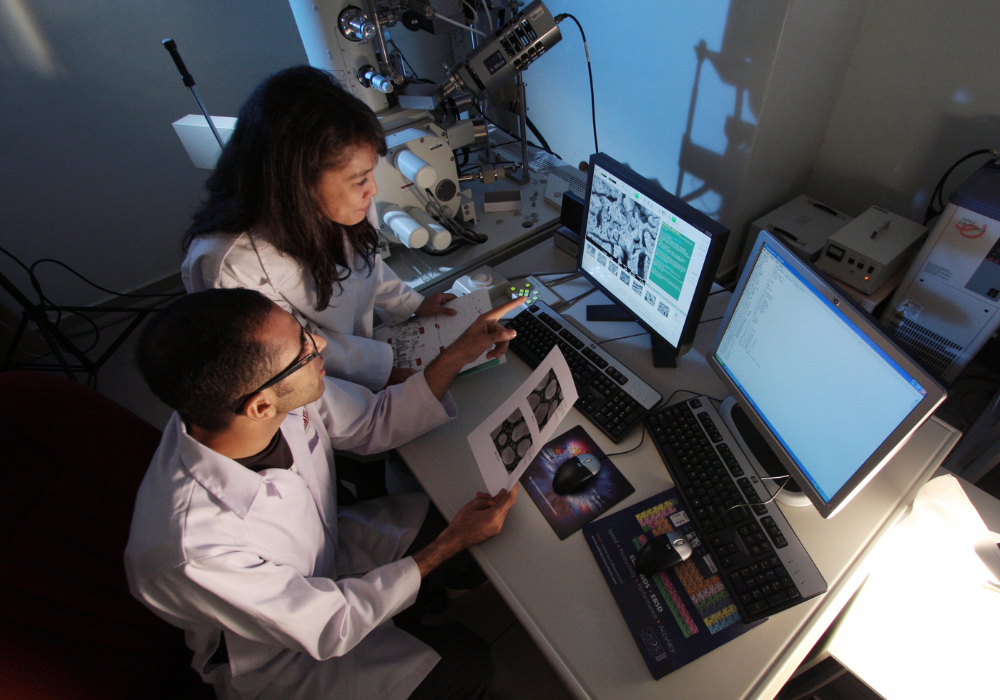

8. The Discovery Was Made Possible by Precision Dating

The research team used accelerator mass spectrometry, a technique that can detect individual atoms of rare isotopes like iron-60. By combining isotope counts with detailed geologic timelines, they reconstructed when and how the debris settled on the seafloor.

This method offers one of the most precise ways to trace cosmic events in Earth’s geological record—essentially allowing scientists to read ancient supernova “fallout layers” like pages in a cosmic history book.

9. Other Isotopes Support the Supernova Hypothesis

Alongside iron-60, scientists also found traces of plutonium-244, another isotope produced only in supernovae or neutron star mergers. The combination of these two rare elements strengthens the case that the signal isn’t contamination or coincidence.

The isotopes appear in matching time layers across different parts of the world, confirming that the source was extraterrestrial and global in scale.

10. Similar Events May Have Happened Before

Earth has likely experienced multiple nearby supernovae over its history. Some researchers propose that periodic bursts of cosmic radiation from such events may even shape long-term biological and climatic cycles.

Fossil evidence suggests certain extinctions and evolutionary bursts roughly align with these intervals. While still debated, it’s possible that supernovae have played a quiet, recurring role in the story of life on Earth.

11. Scientists Are Now Hunting for the Supernova’s Remnant

Astronomers are searching the sky for the leftover “bubble” of gas and dust that would mark the source explosion. Some believe it could correspond to faint x-ray or radio features near the Scorpius-Centaurus region.

If confirmed, that remnant would offer a direct link between the stellar corpse and the isotopic traces here on Earth—an interstellar cause-and-effect story spanning millions of years and hundreds of light-years of space.

12. The Findings Remind Us How Connected Earth Is to the Cosmos

For scientists, the discovery underscores a profound truth: our planet isn’t isolated from the wider universe. From starlight to cosmic dust, Earth continually interacts with its galactic environment.

If a nearby supernova really did sprinkle our world with stardust, it’s a reminder that every atom of life—including us—exists within a cosmic ecosystem. As one researcher put it, “The stars don’t just light up our skies—they shape our history.”