From mummification to the weighing of the heart, ancient Egyptians saw death as a sacred journey to eternal life.

For the ancient Egyptians, death was not an end—it was a transformation. They believed that life, death, and rebirth formed a continuous cycle governed by divine law and cosmic order. From elaborate burial rituals to sacred texts like the Book of the Dead, Egyptians prepared meticulously for the afterlife, ensuring the soul could navigate the challenges awaiting it beyond the tomb. Their complex beliefs, rituals, and monuments reveal not only their fear of death but their profound hope for immortality in a world shaped by gods, balance, and eternal renewal.

1. Death Was Seen as a Transition, Not an Ending

Ancient Egyptians believed that life continued after death in another realm. Death marked a change of state, where the soul—composed of multiple parts—journeyed toward eternal life with the gods. This view made preparing for death a central focus of Egyptian religion.

Because existence after death depended on moral conduct and ritual precision, people of all classes sought ways to preserve their bodies and honor the gods. Through these preparations, Egyptians hoped to achieve ma’at—the divine balance essential for eternal harmony.

2. The Soul Had Many Parts, Not Just One

Egyptian spirituality divided the soul into several components, including the ka (life force), ba (personality), and akh (immortal spirit). Each played a different role in ensuring the deceased’s continued existence.

The ka needed offerings of food and drink, while the ba—often depicted as a human-headed bird—traveled between the living world and the afterlife. When reunited through proper rituals, these elements became the akh, an eternal being that could dwell among the gods.

3. Mummification Preserved the Body for Eternity

Because Egyptians believed the soul needed a physical home, preserving the body was vital. The process of mummification took around seventy days and involved removing internal organs, drying the body with natron, and wrapping it in linen.

Priests performed sacred rites throughout the process, often invoking spells from the Book of the Dead. These acts symbolically transformed the deceased into a divine form, ensuring the spirit could recognize and reinhabit the body after death.

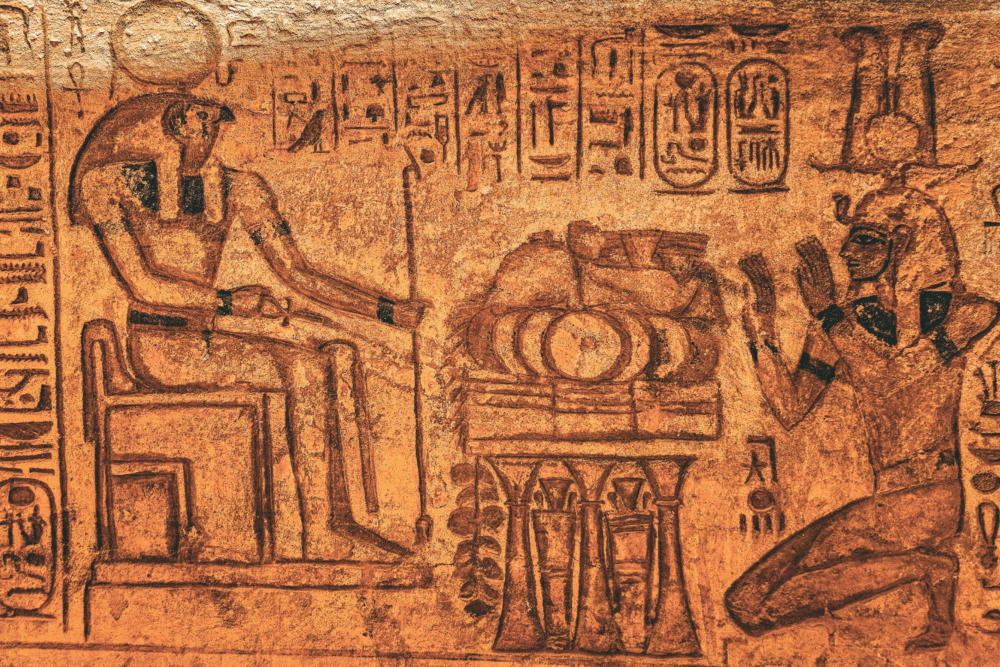

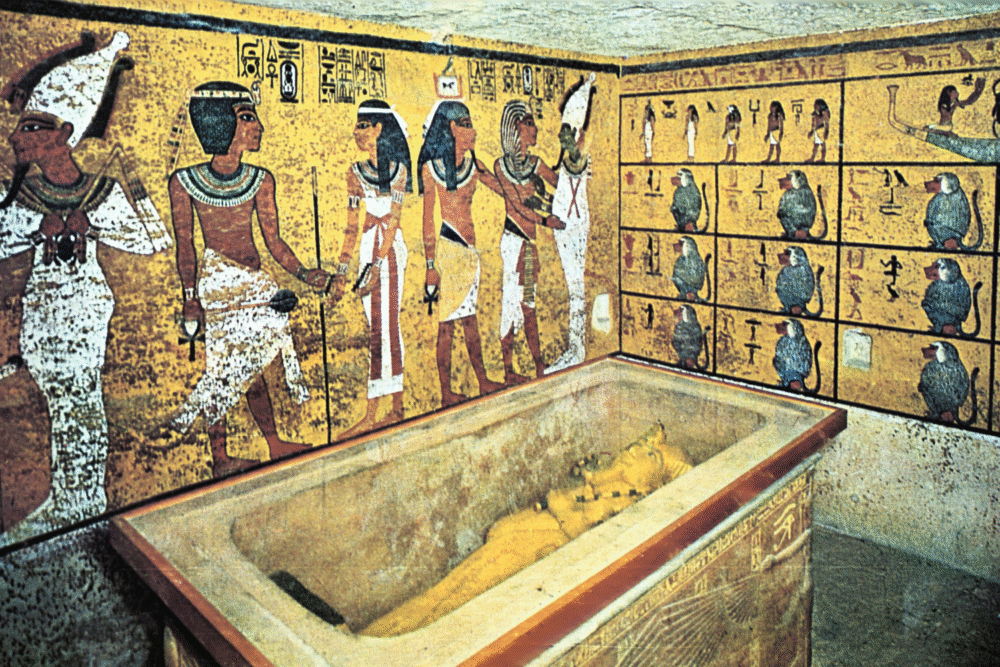

4. Tombs Were Built as Gateways to the Afterlife

Tombs were not just burial places—they were portals connecting the physical and spiritual worlds. Early Egyptians used simple pits, but over time, these evolved into mastabas, pyramids, and elaborately decorated rock-cut tombs.

The walls of these tombs were covered with prayers, spells, and scenes depicting the deceased enjoying eternal life. The architecture and art served both religious and psychological functions—protecting the body and guiding the soul through its cosmic journey.

5. The Journey to the Afterlife Was Filled With Trials

According to Egyptian belief, the soul embarked on a perilous journey after death. Guided by magical spells, it had to pass through regions filled with obstacles, demons, and gates guarded by divine beings.

Texts such as the Amduat and the Book of Gates described this voyage through the underworld, known as the Duat. The soul’s success depended on moral purity and the correct recitation of sacred formulas. Failure meant annihilation, while success granted eternal rebirth.

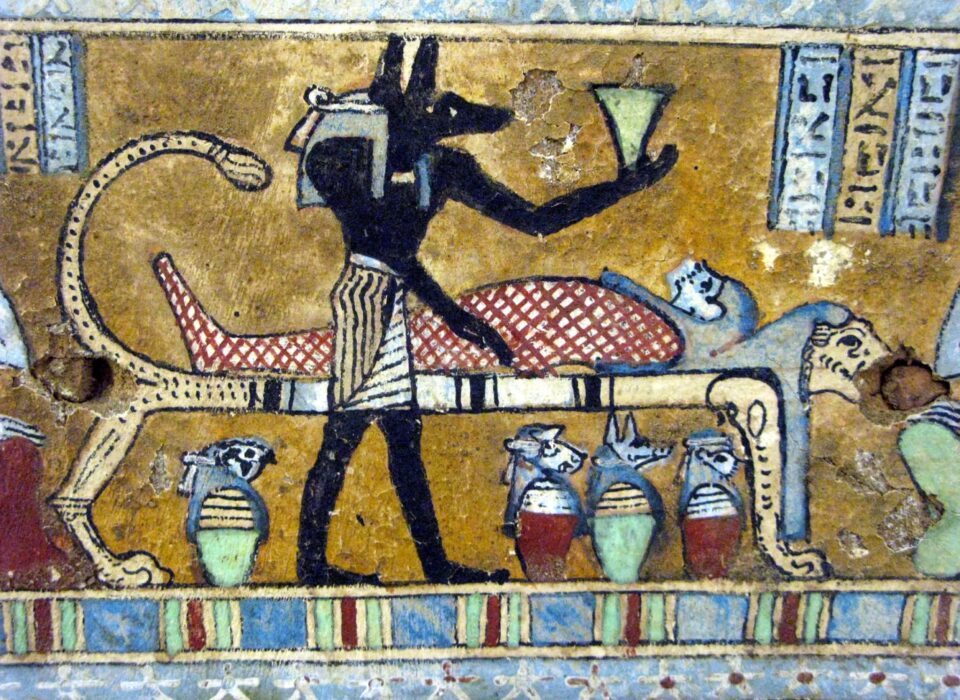

6. The Heart Was the Key to Eternal Judgment

Egyptians believed the heart recorded a person’s deeds and emotions throughout life. During judgment, the god Anubis weighed it against the feather of Ma’at, symbolizing truth and justice.

If the heart balanced with the feather, the soul was declared righteous and welcomed into the afterlife. If it was heavy with wrongdoing, it was devoured by the monster Ammit—a fate worse than death. This belief reinforced moral integrity as essential for eternal salvation.

7. The Book of the Dead Served as a Guide for the Soul

The Book of the Dead was not a single text but a collection of spells and prayers written on papyrus or tomb walls. It provided instructions for navigating the dangers of the Duat and securing eternal life.

These texts included the famous “Negative Confession,” where the deceased declared innocence before forty-two divine judges. By following these spells correctly, the soul could overcome obstacles, earn divine favor, and be reborn among the gods.

8. Offerings Sustained the Dead in the Afterlife

Egyptians believed the dead required nourishment just as the living did. Offerings of bread, beer, meat, and incense were placed in tombs to feed the ka. Families also visited graves regularly to renew these offerings.

Wealthier Egyptians commissioned false doors in their tombs through which the spirit could symbolically receive gifts from the living world. This ongoing relationship between the living and the dead ensured the continued well-being of both.

9. The Underworld Was Ruled by Osiris

Osiris, the god of resurrection, presided over the underworld and judged the souls of the deceased. Once a mortal king, Osiris was believed to have been murdered by his brother Seth and resurrected by his wife Isis.

His triumph over death became a central symbol of eternal life. Egyptians identified closely with Osiris—hoping to share his destiny of rebirth. Every burial and resurrection ritual mirrored the myth of Osiris, linking human fate to divine renewal.

10. Eternal Life Took Place in the “Field of Reeds”

Those judged worthy were welcomed into the Aaru, or Field of Reeds—a paradise resembling an idealized Egypt. There, the righteous lived among family, farmed fertile land, and worshipped the gods forever.

This vision reflected the Egyptian love of order and abundance. Eternal life was not abstract or distant—it was a perfected version of daily existence. The same joys, duties, and hierarchies continued, but without suffering or decay.

11. Funerary Goods Helped the Dead on Their Journey

From amulets to food jars and shabti figurines, tombs were filled with items meant to serve the deceased in the afterlife. Each object carried symbolic meaning and practical function.

Shabtis—small servant statues—were inscribed with spells so they could perform labor on behalf of their owner in the afterlife. Jewelry and charms offered divine protection, while canopic jars safeguarded vital organs under the watch of protective deities.

12. Pharaohs and Commoners Shared Similar Beliefs

While royal burials like Tutankhamun’s are the most famous, the core beliefs about death and rebirth applied to everyone. Pharaohs, nobles, and workers alike prepared for the afterlife according to their means.

Even modest graves contained amulets and prayers invoking divine protection. This universality reflected a deeply egalitarian aspect of Egyptian spirituality: moral righteousness, not wealth, determined one’s fate in the afterlife.

13. Death and Rebirth Were Central to Egyptian Identity

For ancient Egyptians, every sunrise symbolized renewal, mirroring the soul’s rebirth after death. Festivals for Osiris and other deities reinforced the idea that life and death were intertwined cycles, not opposites.

This enduring belief shaped their art, architecture, and daily rituals for over 3,000 years. Through their meticulous preparations for death, the Egyptians achieved what they most desired—to live forever in harmony with the gods and the eternal order of Ma’at.