New Webb images reveal unprecedented detail inside the galaxy’s biggest stellar nursery.

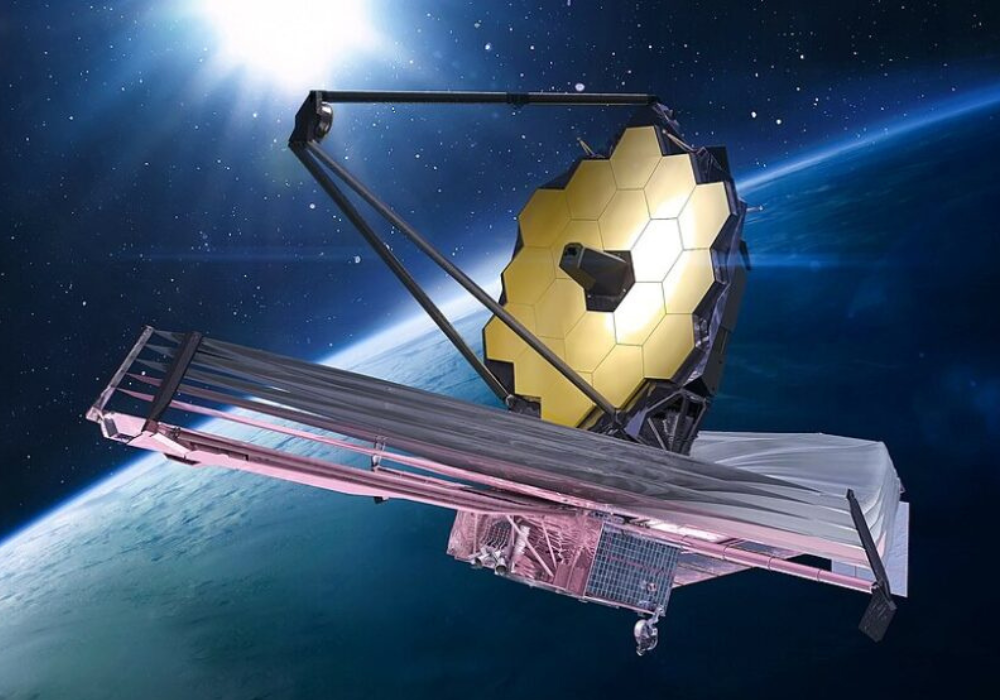

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has delivered the deepest look yet at the Milky Way’s most massive star-forming cloud, Sagittarius B2, revealing glowing stars, gas, and dense dust in unprecedented detail. The giant molecular complex lies near the galaxy’s center and has long puzzled astronomers for its vigorous star production despite limited raw material. Webb’s infrared instruments allow light to penetrate some of the densest regions, exposing young stars and hidden structures that were previously invisible. The new images promise to reshape our understanding of how massive stars emerge in extreme environments.

1. Webb Unveils the Most Massive Star-Forming Cloud

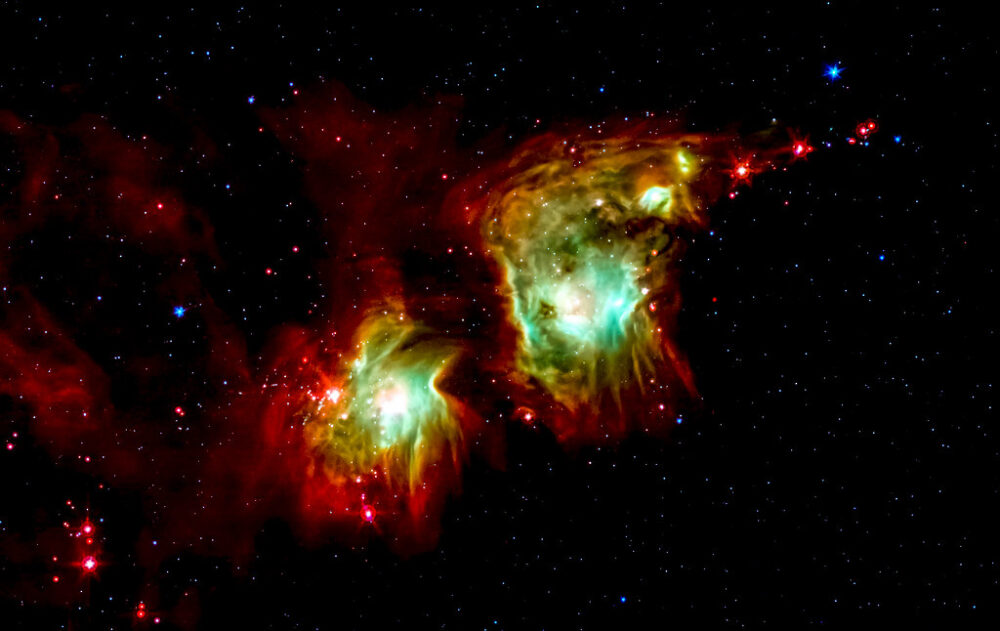

Webb’s instruments have captured Sagittarius B2, the Milky Way’s largest and most active molecular cloud, in unprecedented detail. It sits near the galactic center and has long intrigued astronomers because it forms stars at an unusually high rate compared to its mass.

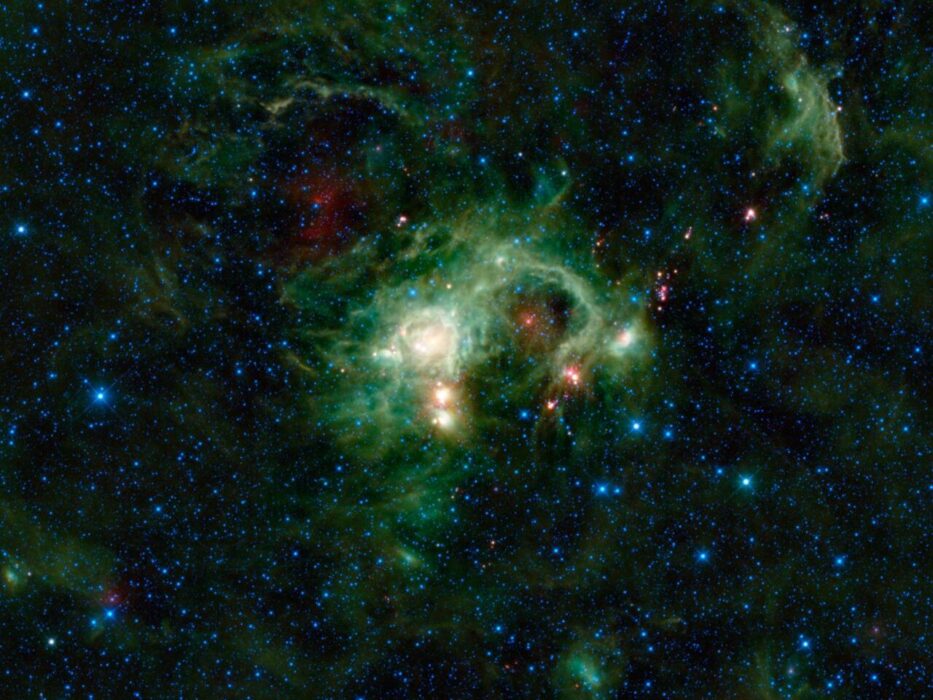

By combining near-infrared (NIRCam) and mid-infrared (MIRI) data, Webb reveals both glowing stars and the dusty, dense gas that surrounds them. The images show intricate structure—voids, filaments, clumps—that were previously invisible, giving scientists fresh data on how the densest parts of our galaxy build new stars.

2. It Produces Disproportionate Stellar Output

Though Sagittarius B2 occupies only a fraction of the galactic center’s gas reservoir, it contributes far more to star formation than its size would suggest. In terms of stellar production per unit mass, B2 outpaces many neighboring regions.

This disparity raises fundamental questions: Why is B2 so efficient at converting gas to stars? Webb offers clues. The data show concentrated zones of activity—hot cores, dense clumps, and emerging H II regions—that help explain why B2 punches above its weight in forming massive stars.

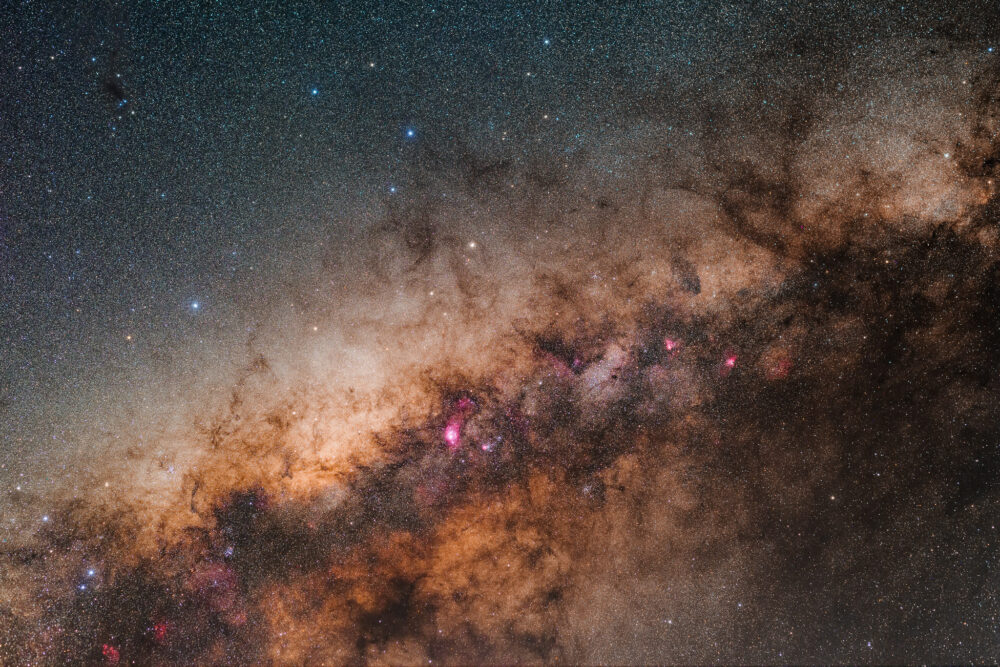

3. Infrared Light Penetrates Dense Clouds

One of Webb’s strengths is seeing through dust that blocks visible light. In both near and mid-infrared wavelengths, the telescope reveals stars hidden inside the thickest parts of B2. Many dark patches in visible images are not empty—they’re just opaque.

In the NIRCam view, many stars appear in orange or red hues; but in the MIRI data, warm dust glows and a different population appears. The contrast between the two instruments helps astronomers discern which regions are dense dust shields and which host active star clusters.

4. Hidden vs. Revealed Stars Revealed

Webb has identified two populations in B2: those visible in near-ir (less obscured) and those deeply embedded in dust (only revealed at longer wavelengths). The deeply embedded objects were largely invisible to earlier telescopes.

This split gives researchers insight into early star formation stages. The hidden stars are in evolutionary phases before they fully ionize surrounding gas or create strong emission. Seeing both populations allows scientists to build timelines of how stars emerge from their dusty cocoons.

5. Discovery of New H II Regions

Using its sensitivity and resolution, Webb has found new candidate H II (ionized hydrogen) regions around massive stars not previously detected. These are regions where young stars’ radiation strips electrons off hydrogen, causing glowing plasmas.

These discoveries suggest that we’ve underestimated the number of energetic young stars in B2. These ionized tear-drops of gas also show how energy escapes through cavities in dense media, influencing surrounding gas and triggering further collapse in adjacent zones.

6. Radiation “Escapes” Through Cavities

Even in extremely dense parts of B2, radiation from young, massive stars is not wholly trapped. Webb has detected infrared photons traveling out through outflow cavities—channels carved by winds or jets.

This finding is key because it shows dense stellar nurseries are not completely closed systems. Radiation leaks influence temperature, chemistry, and dynamics of gas beyond the immediate clump. It also helps explain how light can reveal hidden structures even where gas and dust are thick.

7. Sharp Edges and Cloud Asymmetry

The Webb images show that B2’s eastern edge features a remarkably straight cutoff—a sharp boundary between cloud and void. The gas is unevenly distributed, with some sides denser than others.

That asymmetry is important because it implies external influences—gravity, magnetic fields, tidal forces, or winds from outside the cloud—are sculpting its shape. Understanding these forces helps scientists model how giant clouds evolve near a galaxy’s center.

8. Star Formation May Be Just Beginning

Despite B2’s reputation, Webb’s data suggests that full-scale star formation might only be ramping up in many parts. The telescope did not detect an extended population of lower-mass young stellar objects (YSOs) in all regions, which means many stars in formation are still hidden or in early phases.

That implies this cloud is active yet still evolving. Scientists conclude that much of B2’s star formation may still lie ahead. Monitoring it over time could show how massive clouds transition from inert gas to stellar nurseries.

9. Molecules, Dust, and Chemistry Revealed

Sagittarius B2 has been known for decades as a molecular treasure trove, and Webb’s new data enriches that picture. The mid-infrared view highlights dust heated by nearby stars, and dense gas clumps where complex molecules may live.

By matching molecular emission lines with structure, scientists are closer to mapping how chemistry and star formation interact. In B2, molecules like methanol and organic compounds are more abundant in zones of active heating—offering a view of how planet-building ingredients may arise in extreme environments.

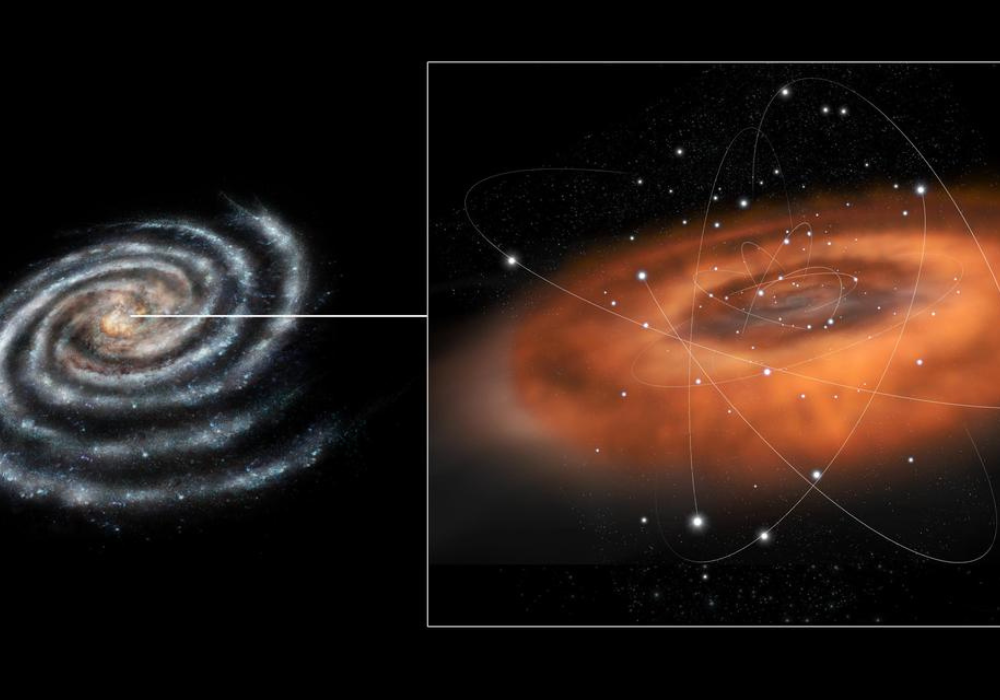

10. Galactic Center Proximity Adds Complexity

B2 lies just a few hundred light-years from Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the Milky Way’s center, and within the galaxy’s Central Molecular Zone—a region with strong gravity, turbulence, magnetic fields, and stellar feedback.

Those extreme conditions make B2 a test case for how star formation works under pressure. Webb’s data will help scientists learn how central galactic environments affect clouds’ ability to collapse, fragment, and birth stars—lessons that apply to galaxies more generally.