Flesh-eating parasites can cause serious skin damage, but global systems help track their spread.

Flesh-eating parasites aren’t science fiction, but their name is more dramatic than medically accurate. These organisms, like those causing leishmaniasis, can destroy healthy tissue by disrupting the body’s own immune response.

They’re typically transmitted through insect bites and favor warm, humid environments. Public health organizations such as the CDC and World Health Organization monitor outbreaks through disease surveillance networks, which help track cases and identify emerging risks before they escalate into larger epidemics.

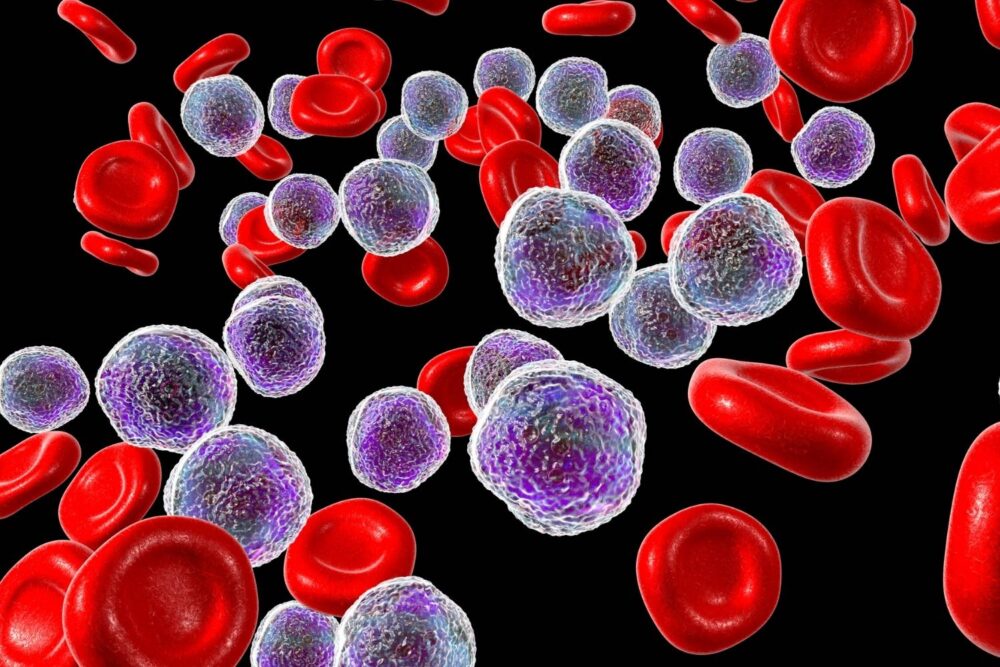

1. Some parasites destroy tissue by triggering the body’s own immune responses.

Tissue-damaging parasites don’t always kill cells directly—instead, some of them trigger hyperactive immune responses that destroy healthy skin and muscle. The damage is often the body’s own defense mechanisms working at the wrong speed, scale, or location, mistaking infected cells for invaders.

In cutaneous leishmaniasis, for example, lesions form not just from the parasite’s arrival but from the inflammation it touches off. A small sandfly bite on the arm can turn into a gaping sore weeks later, with tender edges and weeping skin. The immune system tries to help, but makes matters worse.

2. Flesh-eating parasites are more likely in warm, humid environments.

Moisture and heat support the insects that spread many of these parasites, particularly in regions with dense vegetation and long rainy seasons. Parasites within those insects require warmth to complete their life cycle and survive inside mosquito or sandfly bodies.

Rainforests and subtropical plains offer a kind of open-air incubator for vector-borne infections. But warmer urban environments—with pockets of stagnant water and exposed trash—can also support sandfly populations long enough to boost transmission rates among people and animals nearby.

3. These parasites often enter through cuts or insect bites on skin.

The skin forms a strong barrier, but even a tiny break—like a scratch from a thorn or a healing bug bite—can open a route for parasites. Many rely on insect saliva or contaminated soil to gain entry and reach the tissue underneath.

Once inside, the organisms lodge in collagen-rich areas and begin multiplying quietly. At first, a bite may look like little more than a red bump. Over time, swollen edges and discoloration can signal that the infection has begun to deepen past the upper skin layers.

4. Leishmaniasis is a common parasitic disease that can cause skin ulcers.

Leishmaniasis stems from parasites that enter the skin through insect bites, typically from sandflies. The most common form causes ulcers that start as papules, then evolve into cratered sores with inflamed borders and scab-like crusts—often on exposed areas like arms, face, or ankles.

The name may sound obscure, but in regions from South America to Southwest Asia, these sores are more common than chickenpox. They can heal over months but sometimes leave scarring. Severe cases can spread to mucous membranes if treated late, complicating recovery and eroding nose or mouth tissue.

5. Not all infections from parasites are immediately visible or painful.

Some parasitic infections produce few or delayed symptoms, making early detection difficult. Tissue changes can occur deep below the skin or in less visible areas, where a person might not notice damage until discomfort or swelling sets in.

In mucocutaneous forms of leishmaniasis, for example, infection silently migrates from healed skin wounds to the nasal cavity. Discoloration, crusting, or nosebleeds may not appear for months. Without internal imaging or lab testing, the parasite’s full reach inside the body can remain hidden until it causes more dramatic symptoms.

6. Many cases are tracked through a global network of health organizations.

Health officials use interconnected disease surveillance networks to monitor outbreaks of tissue-damaging parasites. Global systems collect data from hospitals, labs, and field workers to spot spikes in symptoms and track where transmission is occurring most frequently.

If a cluster of patients in a border town reports similar lesions within weeks, that can trigger an alert to nearby regions and international partners. From satellite phones in remote clinics to encrypted emails between ministries, these systems aim to catch patterns before isolated cases become widespread outbreaks.

7. Some parasites can live unnoticed in the body for months or years.

Some parasites enter a dormant state that delays symptoms for months or even years. During this quiet phase, they may reside in soft tissue or organs, avoiding immune detection while slowly affecting cells or preparing for later expansion.

A person could carry Leishmania from a childhood bite in Brazil and only develop signs decades later under stress or weakened immunity. Residual scars or inflamed lymph nodes might offer the first hint. That long silence complicates both treatment timelines and tracing the original exposure event.

8. Dogs and rodents are common carriers of tissue-damaging parasites.

Certain animals act as domestic or wild reservoirs for parasites, harboring them without obvious illness. Dogs, in particular, can carry Leishmania without showing skin lesions, while rodents can maintain parasite levels in burrows or nests near human homes.

In Mediterranean towns, infected stray dogs often enable parasites to persist even as human cases fluctuate. Rodents like sand rats and gerbils in Central Asia host the same parasites that cause outbreaks in nearby villages. These carriers play a hidden but steady role in maintaining transmission cycles.

9. Researchers monitor parasite spread by mapping insect vector habitats.

To anticipate future outbreaks, researchers map habitats where insects thrive—especially areas with thick vegetation, humid microclimates, and host animals. Integrating satellite imagery with weather, terrain, and insect trap data, scientists can forecast where vectors may increase.

For instance, if rainfall creates new puddles near a forest edge, and nearby dogs have tested positive, field teams might predict sandfly expansion. Maps highlight risk zones, guiding vaccination of domestic animals or larvicide application without waiting for new human cases to appear first.

10. Sandflies are known to transmit parasites that target human skin cells.

The sandfly, a tiny buzzing insect smaller than a mosquito, is a primary vector for skin-targeting parasites like Leishmania. When it feeds on an infected animal’s blood, the parasite enters the fly’s gut and later travels to its mouthparts.

Then, during its next bite, the sandfly passes parasites into the fresh break in human skin. Unlike a bite from a horsefly or wasp, this one may go unnoticed—leaving a few invisible passengers behind. The wound’s size doesn’t reflect the threat it carries.

11. Climate shifts can influence the geographic range of parasite carriers.

Warmer average temperatures change where insects like sandflies or ticks can survive year-round and reproduce. As regions formerly too cold begin to support these vectors, maps of parasite risks grow more complex—and less limited to remote or tropical zones.

In parts of Southern Europe, sandflies now breed in places they hadn’t decades ago. Insect surveys confirm their spread upward into hillside towns and cooler plains. As habitats shift, so does the window of exposure for humans and animals living nearby or passing through.

12. Surveillance programs track cases to help prevent future outbreaks.

Ongoing surveillance helps public health teams respond early to infections that might otherwise spread widely. Databases from clinics, lab test results, and patient interviews feed into national and international monitoring dashboards that track new cases over time.

When an unusual pattern appears—a spike in non-healing skin ulcers, for example—officials can investigate swiftly. That leads to faster diagnoses, resource allocation, and in some cases, insect control efforts. The goal isn’t just to treat, but to break the cycle of transmission before it reaches more people.