New research shows the San Andreas Fault and Cascadia Subduction Zone may be connected—raising earthquake risks along the U.S. West Coast.

Scientists have uncovered compelling geological evidence that two of North America’s major fault lines—the San Andreas Fault in California and the Cascadia Subduction Zone off the Pacific Northwest—may sometimes move in tandem. Sediment cores from offshore off northern California show “doublets” of underwater landslides caused by seismic shaking in both fault systems within minutes to hours of each other. Although this doesn’t mean an earthquake is imminent, researchers say the link could amplify risks for millions living along the coast.

1. Scientists Discover Signs of Two Fault Systems Moving Together

Geologists studying sediment off the coast of northern California have found evidence that the San Andreas Fault and the Cascadia Subduction Zone—two of North America’s largest fault systems—may sometimes move in tandem. The discovery was made through deep-sea sediment cores showing simultaneous underwater landslides caused by past quakes.

These “paired” seismic signals suggest that major movement along one fault may trigger or influence movement along the other. Researchers say understanding how these systems interact could be critical to predicting large-scale seismic events on the U.S. West Coast.

2. The San Andreas Fault Stretches Across California

The San Andreas Fault is one of the most studied fault lines on Earth, marking the boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates. It runs roughly 800 miles from the Salton Sea in Southern California to Cape Mendocino in the north.

This fault is responsible for some of California’s most destructive earthquakes, including the 1906 San Francisco quake and the 1989 Loma Prieta event. Scientists monitor it constantly because even small shifts can influence stress levels in nearby faults across the state.

3. The Cascadia Subduction Zone Lies Just Offshore

The Cascadia Subduction Zone runs roughly 700 miles from northern California to British Columbia. Here, the oceanic Juan de Fuca Plate is being forced beneath the North American Plate—a process that builds immense geological pressure over centuries.

When that pressure releases, it can cause “megathrust” earthquakes exceeding magnitude 9.0, along with devastating tsunamis. The last major Cascadia event occurred in 1700, and scientists say the region is due for another large quake in the coming centuries.

4. New Data Shows Seismic Events May Be Linked

Recent studies published in Geophysical Research Letters reveal that underwater landslides and sediment layers off California’s coast occur in matching timeframes for both fault zones. This pattern implies simultaneous or closely timed shaking from two separate seismic sources.

While the events likely weren’t triggered by one continuous rupture, researchers say they demonstrate how stress changes in one fault system could influence activity in another hundreds of miles away. Such coupling challenges traditional assumptions that major faults act independently.

5. Linked Fault Movement Could Intensify Earthquake Damage

If the San Andreas and Cascadia faults were to move in quick succession, their combined energy could have catastrophic effects across the western United States. Scientists estimate that synchronized or sequential quakes could magnify ground motion and duration.

This would increase the likelihood of landslides, infrastructure failure, and long-lasting aftershocks. Coastal regions could also experience overlapping hazards—such as shaking from the San Andreas Fault followed by tsunamis generated by Cascadia’s offshore movement.

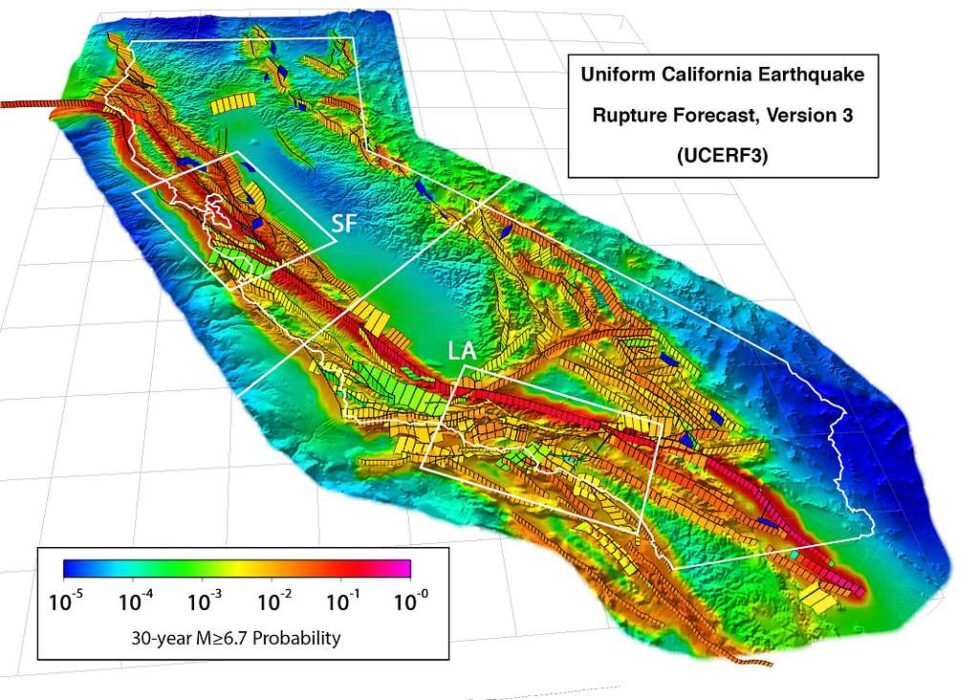

6. The Discovery Changes Earthquake Risk Models

Most seismic hazard maps treat fault zones as separate systems with localized effects. The new findings suggest that some faults may share deeper stress connections, requiring updated risk assessments for the Pacific Coast.

Researchers are now revising computer simulations to model how energy transfer between distant faults could occur. The goal is to understand whether stress waves from one quake could destabilize neighboring fault zones, leading to cascading seismic activity.

7. Historical Evidence Supports the Link

Geological records show that several major California earthquakes occurred around the same time as offshore disturbances farther north. Layers of disturbed ocean sediment—called “turbidites”—align with known seismic events on land.

These correlations provide physical proof that multiple fault systems may have slipped within hours or days of each other in the past. The findings echo historical accounts from Indigenous oral traditions that describe prolonged shaking and coastal flooding centuries ago.

8. Cascadia Could Trigger San Andreas—or Vice Versa

Scientists believe that stress transfer from one major fault could act like a “domino effect,” nudging adjacent faults closer to failure. While the two systems are separated by hundreds of miles, they’re connected through deep crustal structures that can transmit seismic energy.

If Cascadia ruptured first, it could alter the stress field across California, increasing strain along the San Andreas. Likewise, a massive San Andreas event could send energy northward, destabilizing parts of the Cascadia Subduction Zone sooner than expected.

9. Coastal Communities Could Face Dual Threats

If both faults moved in the same period, the combined effects could devastate communities across the Pacific Coast. Cities such as San Francisco, Eureka, Portland, and Seattle could experience strong ground motion, while low-lying coastal towns face the added risk of tsunamis.

Emergency planners emphasize that even though such a scenario is rare, preparedness is essential. Improved evacuation routes, resilient infrastructure, and regional communication systems would be crucial to surviving overlapping disasters.

10. Scientists Are Expanding Monitoring Efforts

In response to these findings, research teams are deploying more ocean-bottom seismometers and pressure sensors along the West Coast. These devices will capture high-resolution data from deep below the seafloor, providing insight into stress accumulation and small precursory tremors.

The hope is that continuous monitoring will help detect patterns indicating when two fault systems are interacting. By linking offshore and onshore seismic networks, scientists aim to build a real-time understanding of how energy moves through the region’s tectonic framework.

11. The Findings Don’t Mean a Megaquake Is Imminent

Despite public concern, researchers stress that the new evidence doesn’t indicate an immediate threat of simultaneous fault rupture. Instead, it highlights how complex and interconnected the Earth’s crust can be.

Understanding these links allows scientists to refine long-term hazard assessments, not to predict specific earthquakes. The goal is to prepare communities more effectively and strengthen infrastructure in regions where seismic risks overlap. As experts note, knowledge—not panic—is the best form of preparedness.