Decoded tablets reveal how Babylonians read lunar eclipses as warnings of doom for kings and kingdoms.

A clay tablet can’t shout, but this one comes close: it warns that under certain skies, “a king will die.”

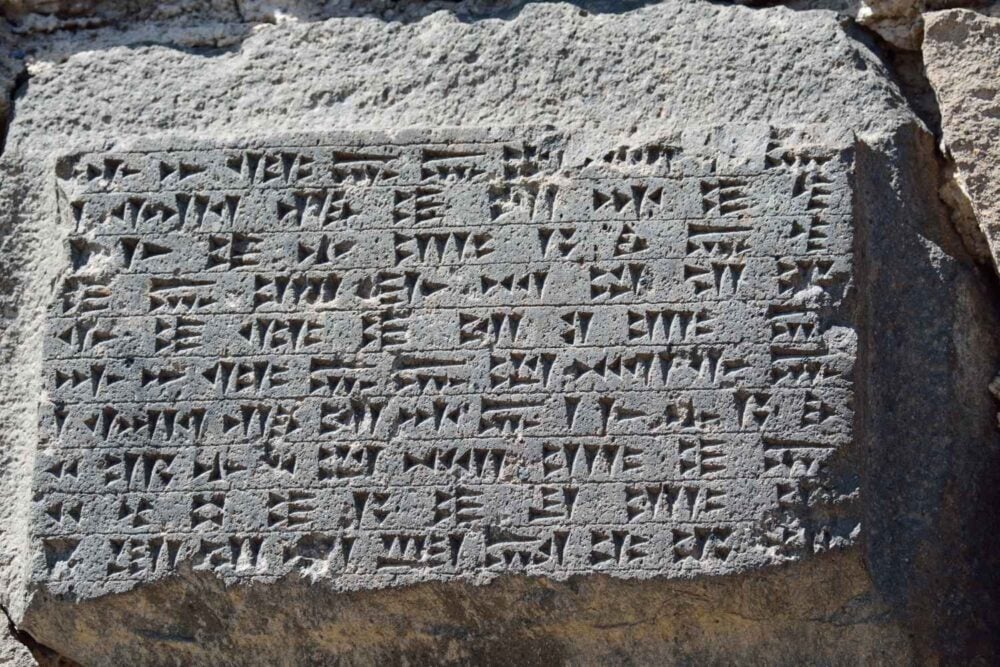

Researchers have now fully translated four 4,000-year-old Babylonian cuneiform tablets that link lunar eclipses to specific omens: war, famine, plague, and political collapse. The tablets sat in a museum collection for decades, mostly unread.

The texts don’t predict the future in a modern sense. They show how trained advisors watched the moon, matched eclipse details to an omen list, and then tried to protect the ruler with tests and rituals. It’s a window into a world where the night sky felt like a coded message.

1. The tablets were known, but their full message wasn’t

These four clay tablets entered museum collections in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but translating them completely took time. Cuneiform is dense, damaged sections can be tricky, and specialists are relatively rare.

Only recently did researchers finish a full reading and publish it in an academic journal. That matters because it turns scattered lines into one coherent text—an organized list of eclipse omens. Now other experts can re-check the readings, debate the meanings, and compare them with related omen traditions from Mesopotamia.

2. They’re the oldest compiled lunar-eclipse omen texts yet found

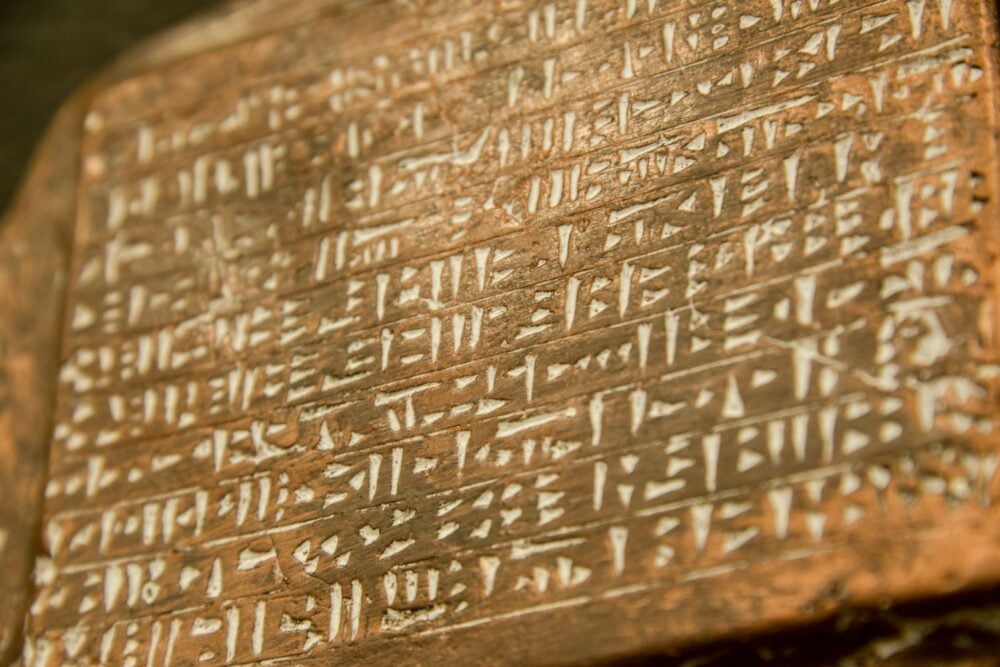

The study describes the tablets as the earliest known compendia of lunar-eclipse omens—essentially a handbook. Instead of a single prediction, they collect many scenarios and the outcomes those scenarios were believed to signal.

The tablets likely originated in Sippar, a major Babylonian city. Their existence suggests scholars were already building standardized systems for interpreting the sky, complete with shared rules and training passed between generations.

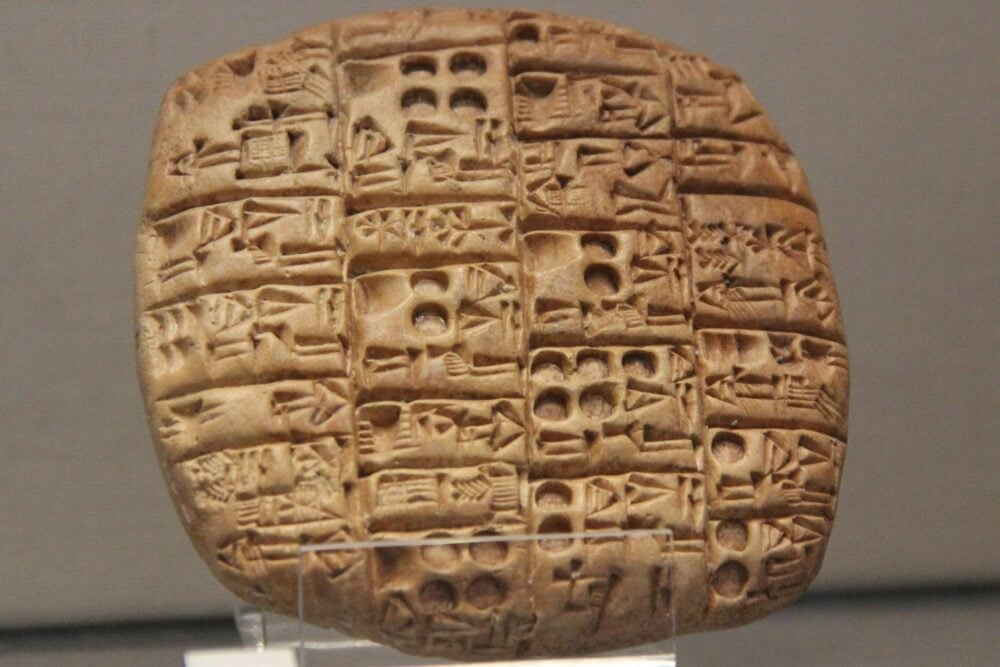

3. The omens tie eclipse details to specific threats

These aren’t vague fortunes. The text links particular eclipse patterns—where darkness begins, how it clears, and the time of night—to concrete fears like pestilence, famine, invasion, and even the death of a ruler.

One line famously warns that if an eclipse darkens and clears all at once, “a king will die,” often paired with disaster for rival lands. Other entries describe loss of cattle or military defeat, revealing how wide the range of anxieties truly was.

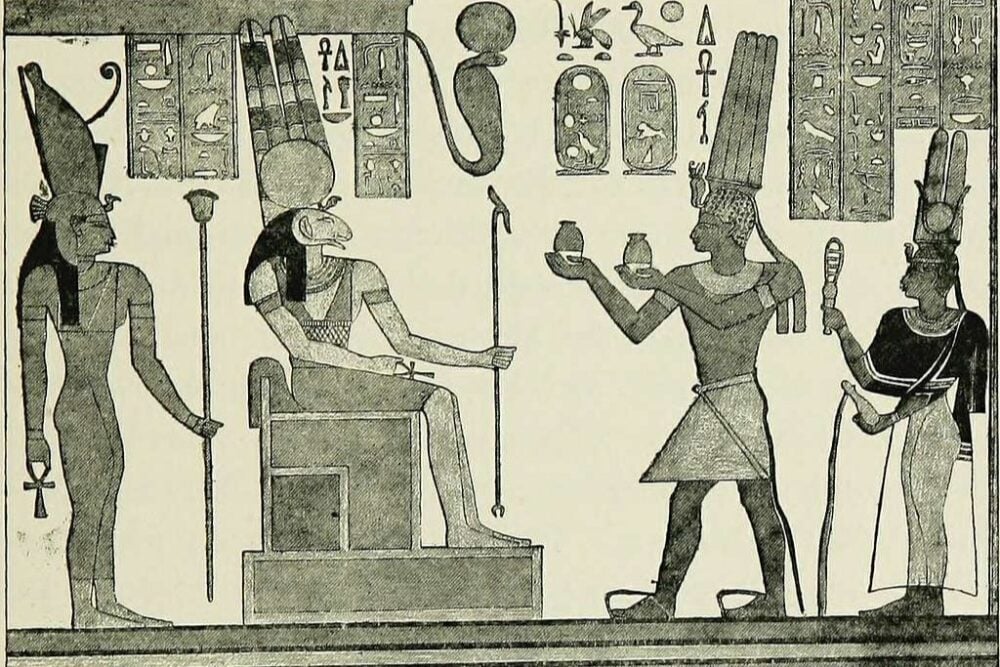

4. The moon mattered because it felt like a message

To Babylonian elites, celestial events weren’t just beautiful or interesting. They were treated as intentional signs placed by the gods, meant to be read and interpreted.

That belief made astronomy practical. Watching the sky was part of governing, alongside diplomacy and force. Ignoring an eclipse wasn’t just careless—it could feel dangerously irresponsible.

5. The system behind the omens was surprisingly methodical

The tablets organize predictions by measurable details: month, day, time of night, duration, and shadow movement. Observers weren’t guessing—they were matching observations to a structured reference.

This implies trained specialists who recorded events carefully and consulted an established body of knowledge. Even though the conclusions were supernatural, the method relied on consistency, classification, and shared expertise.

6. Some omens may reflect real remembered disasters

Researchers suggest some entries may trace back to lived experience. An eclipse followed by disaster could have cemented a lasting association in cultural memory.

Many links were likely symbolic rather than statistical. Still, the omens reveal what leaders feared most—death of the king, famine, war, disease, and collapse—forming a catalogue of state-level anxiety.

7. A dire omen triggered a second “test”

If an eclipse omen looked especially dangerous, advisors didn’t stop there. They performed an additional ritual test by examining the entrails of a sacrificed animal to see if the threat was immediate.

This acted as a verification step. Only if multiple signs aligned would officials move toward protective actions. Even within a supernatural framework, confirmation mattered.

8. Rituals were meant to cancel the bad future

Babylonians believed ominous signs could sometimes be neutralized through correct ritual action. A warning from the gods didn’t always mean fate was sealed.

Later traditions even used “substitute kings” to absorb divine wrath. Whether or not that applied here, the tablets fit a broader belief: humans could respond to warnings rather than passively accept them.

9. The tablets read like a checklist of ancient fears

The dangers listed—plague, famine, invasion, rebellion, assassination—show how fragile ancient states could be. A single failure could ripple outward.

Even without belief in omens, the tablets map social pressure points. They show what officials monitored closely and what they feared losing control over.

10. Astronomy and religion worked side by side

Sky observation wasn’t separated into science and faith. The same careful tracking that predicted eclipses fed religious interpretation and political decision-making.

These tablets sit at that intersection. They show knowledge being built, recorded, and taught, all aimed at protecting the state and its ruler.

11. Why this translation matters today

Deciphering these tablets deepens understanding of how Mesopotamian societies organized knowledge and managed fear. They turned a terrifying sky event into a structured response plan.

It’s also a reminder that new discoveries don’t always come from new excavations. Sometimes they emerge when old artifacts are finally read in full, restoring voices to people who once stared at a darkened moon and tried to keep their world from falling apart.