Most Americans struggle with these civics questions—could you get them right?

Most people assume they know the basics about their own country—until they’re put to the test. The truth is, questions that new citizens are required to answer often leave lifelong Americans scratching their heads. From history lessons that faded after high school to government details many take for granted, it’s easy to realize how quickly the knowledge slips away. What seems simple on the surface can suddenly feel tricky when the pressure’s on.

1. What is the supreme law of the land?

The answer is the U.S. Constitution. While most people know it exists, fewer could explain why it matters. The Constitution is the foundation of all American laws and sets the boundaries for how government works. Without it, the country would have no clear framework to follow.

It also protects basic freedoms like speech and religion. What’s surprising is that many lifelong Americans have never read it, even though every law must align with it. For new citizens, this is one of the most important lessons about what makes the United States unique.

2. What do we call the first ten amendments to the Constitution?

The correct answer is the Bill of Rights. These amendments guarantee personal freedoms most Americans take for granted, like freedom of the press, the right to a fair trial, and protection from unreasonable searches. They’re central to the American identity.

Still, many people can’t list more than one or two of them. The Bill of Rights is taught in school, but unless you’re a lawyer or history buff, it often gets fuzzy. For immigrants preparing for citizenship, remembering this answer can mean the difference between passing or failing the civics test.

3. What is one right or freedom from the First Amendment?

Common answers include freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of assembly. The First Amendment packs a lot into just a few words, making it one of the most cited parts of the Constitution.

Americans use these rights every day—whether protesting, posting on social media, or attending religious services. Yet not everyone can actually name which freedoms are included. New citizens must know at least one, but longtime citizens often get tripped up when asked. It’s a reminder of how central these rights are, even if they’re sometimes overlooked.

4. How many U.S. senators are there?

There are 100 senators, with two representing each state. That means tiny states like Vermont and huge states like California have the same number of votes in the Senate. It’s a setup designed to balance the interests of small and large states.

Still, this number surprises many Americans, especially when they confuse senators with representatives. Congress is a two-part system, and while the House has hundreds of members, the Senate always sticks at 100. For citizenship applicants, memorizing this number is key to understanding how power is divided in Washington.

5. We elect a U.S. senator for how many years?

The correct answer is six years. Unlike members of the House, who serve for two, senators stay in office longer to provide stability. This staggered system ensures that only about one-third of the Senate is up for election every two years.

Many Americans forget this detail, mixing it up with other terms of office. But the six-year length is meant to give senators time to focus on long-term issues rather than short-term popularity. It’s a small detail, but it shows how the U.S. government was carefully designed to balance change with continuity.

6. How many voting members are in the House of Representatives?

There are 435 voting members, a number that has remained fixed since 1929. Seats are divided among states based on population, which means larger states like Texas and California have far more representatives than smaller states like Wyoming.

The math behind this system is updated every ten years with the census. Yet despite its importance, many Americans don’t know the exact number. The difference between the House and the Senate can feel confusing, but it’s one of the most important aspects of how Congress operates. New citizens are expected to memorize it.

7. Who vetoes bills?

The president of the United States has the power to veto legislation. That means even if Congress passes a bill, it doesn’t automatically become law. The president can reject it, forcing lawmakers to either revise it or attempt to override the veto with a two-thirds vote in both chambers.

It’s a strong check on congressional power, but one not often discussed outside election seasons. Many Americans forget this detail, even though vetoes have shaped history. For example, presidents from Andrew Johnson to modern leaders have used vetoes to push back on controversial laws.

8. Who is the Commander in Chief of the military?

The president holds this role as well. While Congress declares war and controls funding, the president directs the armed forces. This balance of power was intentionally created to prevent one branch of government from gaining too much control.

Despite being common knowledge during election debates, some people forget the exact title. Immigrants preparing for the test have to know it, because it reflects how the U.S. combines civilian leadership with military power. It’s another example of the Constitution’s checks and balances at work.

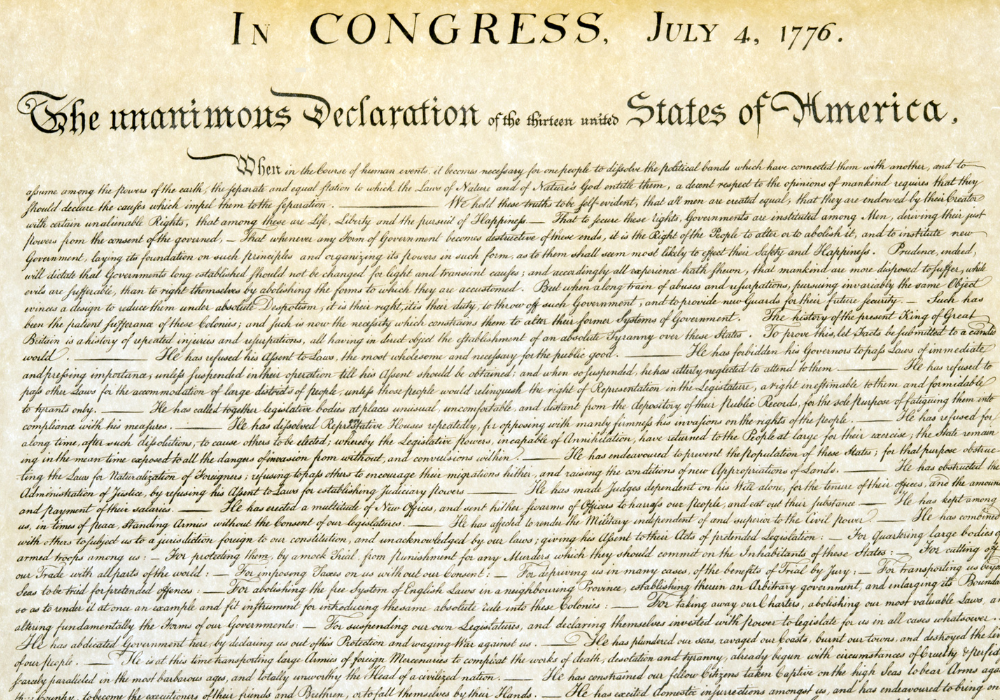

9. Who wrote the Declaration of Independence?

Thomas Jefferson is credited as the main author. Although it was a group effort with edits from other Founding Fathers, Jefferson drafted most of the document. His words about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness remain some of the most quoted lines in American history.

Still, many Americans confuse Jefferson with Benjamin Franklin or George Washington. The Declaration is one of the country’s most celebrated documents, yet the details behind it often blur over time. For citizenship applicants, remembering Jefferson’s name is a must.

10. When was the Constitution written?

The Constitution was drafted in 1787, after the failure of the Articles of Confederation. That year marked the birth of the framework that still governs the U.S. today. The Philadelphia Convention brought together delegates to design a stronger system of government.

Most Americans know the Constitution is “old,” but they often can’t recall the exact year. New citizens, however, must learn it as part of the civics test. Remembering 1787 ties directly to understanding how America built its foundation after independence.

11. Who was the first President?

George Washington is the correct answer. His leadership during and after the American Revolution made him a natural choice. Washington also set many traditions for the presidency, such as serving only two terms.

Even though he’s one of the most famous figures in American history, many people get fuzzy on the details of his role. Citizenship applicants can’t afford to miss this one, as it’s among the most straightforward questions on the test.

12. Name one war fought by the United States in the 1900s.

Acceptable answers include World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Gulf War. The U.S. was deeply involved in global conflicts during the 20th century, shaping both world history and its own place as a superpower.

Despite these wars being part of school history lessons, many Americans struggle to recall the timelines. For immigrants preparing for citizenship, naming just one of them is enough. But the question highlights how deeply war influenced the U.S. during that century.

13. What movement tried to end racial discrimination?

The Civil Rights Movement is the answer. Led by figures like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, it transformed American society during the 1950s and 1960s. The movement fought against segregation, pushed for voting rights, and demanded equal treatment under the law.

While most Americans recognize the term “civil rights,” not everyone remembers the specific historical context. For citizenship applicants, this question highlights a critical part of the nation’s modern history—showing that democracy isn’t just about founding documents but also about continued struggles for equality.