Their legendary journey mapped a new nation—but what happened after the expedition was far darker than most Americans realize.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition is often celebrated as a triumph of courage and exploration—a journey that opened the American West and defined a new nation’s sense of possibility. But when the Corps of Discovery returned home in 1806, the glory they expected didn’t last. Fame gave way to politics, rivalry, and disillusionment as the explorers faced a country already moving on. What began as an adventure of unity and discovery would end with a tragedy few Americans ever heard about.

1. A Presidential Mission Begins

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned an expedition to explore the Louisiana Territory and find a route to the Pacific Ocean. He wanted scientific data, trade opportunities, and a clearer understanding of the vast new land acquired through the Louisiana Purchase. Jefferson chose his personal secretary, Captain Meriwether Lewis, to lead the mission.

Lewis, in turn, selected William Clark—an experienced frontiersman and military leader—as co-captain. Together, they were charged with mapping the uncharted West, studying its plants and animals, and establishing relations with Native nations along the way.

2. Preparing for the Unknown

Throughout the winter of 1803–1804, Lewis and Clark gathered supplies and trained their men at Camp Dubois, near present-day St. Louis. The expedition’s 45 members included soldiers, scouts, craftsmen, and interpreters—plus Clark’s enslaved man, York, and Lewis’s Newfoundland dog, Seaman.

They studied astronomy, navigation, and medicine, ensuring the group could survive in complete isolation. Lewis also spent months in Philadelphia studying botany and zoology under leading scientists. By spring, the Corps of Discovery was ready to embark on one of the most ambitious journeys in American history.

3. The Expedition Sets Out

On May 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery departed from St. Louis, pushing westward up the Missouri River in boats laden with supplies and scientific instruments. Progress was slow; the current was fierce, and sandbars constantly shifted beneath them.

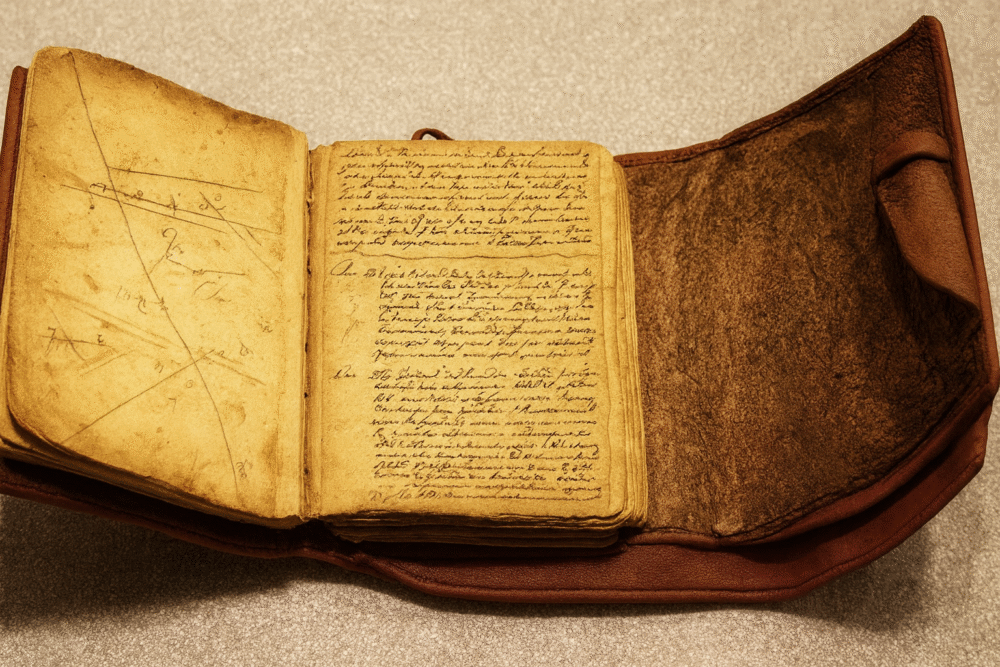

Along the way, they kept detailed journals, recording unfamiliar plants, animals, and weather patterns. The team averaged only 15 to 20 miles per day, but their meticulous mapping and observation laid the foundation for America’s first true understanding of its new western territories.

4. Encounters With Native Nations

From the start, the expedition depended on diplomacy with Native American nations. The Corps traded goods, offered peace medals from Jefferson, and gathered information about local customs and geography. Their early contacts with the Oto, Omaha, and Teton Sioux tested their negotiation skills and patience.

Later, near present-day North Dakota, the Mandan and Hidatsa welcomed them, providing food and advice for surviving the winter. These encounters were crucial to the expedition’s survival and success. Without the cooperation and knowledge of Indigenous peoples, the journey would likely have ended in failure.

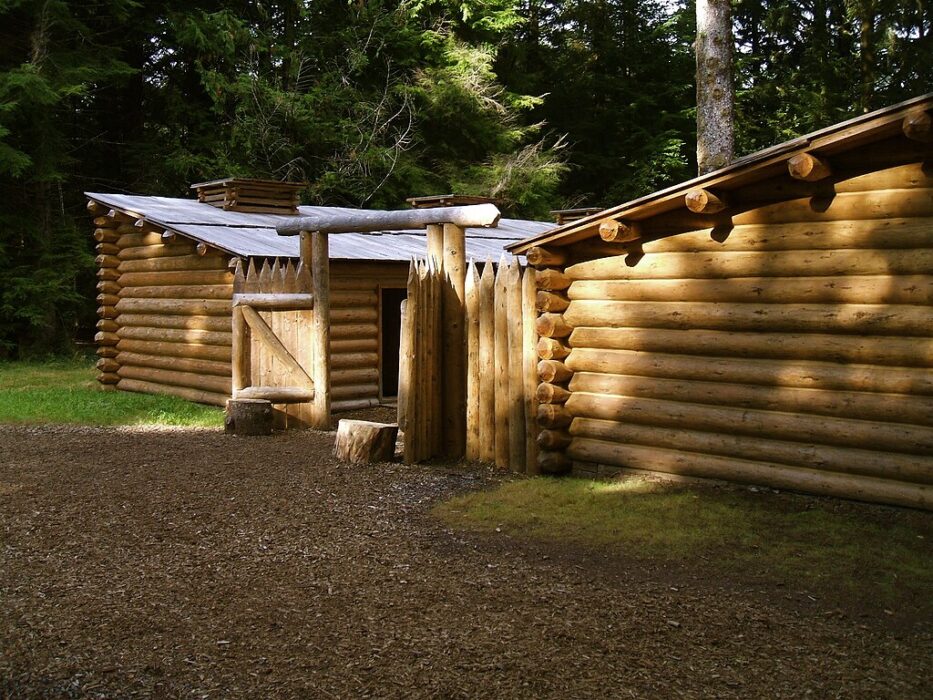

5. Wintering at Fort Mandan

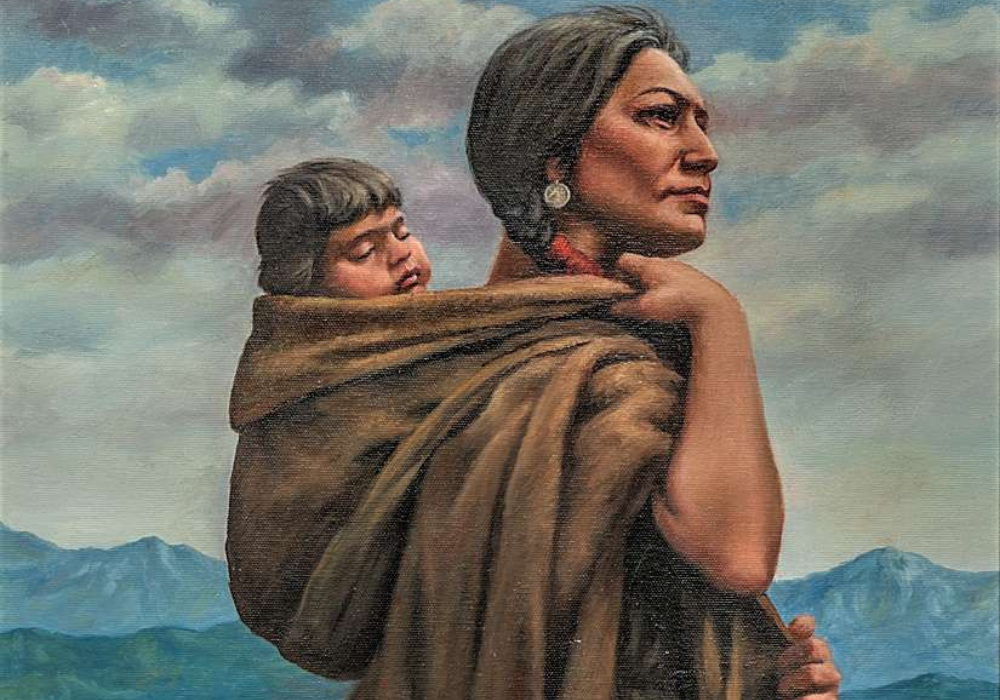

By late 1804, freezing temperatures forced the expedition to build Fort Mandan, where they would stay for the winter. There, they met Toussaint Charbonneau and his young Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, who would later become invaluable guides.

During the long, frigid months, the Corps repaired equipment, documented local wildlife, and sent reports and specimens back east. They also solidified relationships with the nearby tribes. When the snow began to thaw in the spring of 1805, the team was prepared for the next and most difficult phase of their journey.

6. The Journey Through the Rocky Mountains

In spring 1805, the Corps traveled up the Missouri River toward the Rockies. Sacagawea proved essential, helping translate and identify landmarks familiar to her Shoshone people. When the expedition reached the Continental Divide, they realized that Jefferson’s dream of a single water route to the Pacific was impossible.

Crossing the rugged, snow-covered peaks nearly broke the group. Food was scarce, and exhaustion was constant. Yet through sheer determination and the help of Indigenous allies, the explorers endured, paving the way to the Pacific Northwest and a new chapter in geographic knowledge.

7. Reaching the Pacific Ocean

After more than a year of hardship, the Corps of Discovery finally reached the Pacific Ocean on November 15, 1805. They had crossed the continent, mapping rivers and mountains no American had seen before.

They built Fort Clatsop near the Columbia River and spent the winter of 1805–1806 there. The team faced relentless rain and limited food but recorded detailed observations about the coast’s environment and wildlife. Though weary, they had achieved their mission: reaching the Pacific and confirming that a transcontinental passage was possible, even if not all by water.

8. The Long Return Home

In March 1806, the expedition began its journey home. Traveling eastward, they followed some familiar routes but also split up briefly to explore additional areas, including the Yellowstone and Marias Rivers.

By the time they reached St. Louis in September, they had been gone for over two years and covered nearly 8,000 miles. Their arrival was met with celebration and astonishment. The explorers brought back maps, journals, plant specimens, and invaluable knowledge that would change America’s understanding of its own geography.

9. A Triumph That Changed a Nation

The Lewis and Clark Expedition transformed America’s vision of itself. Their findings mapped the continent’s heart and opened the door for expansion and trade. They documented more than 200 new plant and animal species and charted countless miles of river and mountain terrain.

But the expedition also marked the beginning of profound changes for Native Americans, whose lands and autonomy would soon face growing pressure. The Corps’ achievements were scientific and national triumphs, yet they also set in motion the westward expansion that would alter Indigenous life forever.

10. Adjusting to Life After Glory

When Lewis and Clark returned, both men were celebrated as heroes. Lewis was appointed governor of the Louisiana Territory, while Clark became the superintendent of Indian affairs. Yet public recognition didn’t translate into personal satisfaction.

Lewis struggled with the burdens of leadership and paperwork, while Clark found himself caught in the politics of federal administration. The excitement of exploration gave way to bureaucracy and frustration. For men who had once navigated the wilderness freely, the constraints of political life were difficult to bear.

11. The Burdens of Fame and Responsibility

As governor, Lewis faced challenges managing vast territories with little funding or support from Washington. He clashed with local officials and struggled to document the expedition’s findings for publication.

Mounting debts and administrative disputes weighed heavily on him. Meanwhile, the nation had already turned its attention elsewhere, and the excitement surrounding the expedition began to fade. The public’s short memory left Lewis feeling isolated and misunderstood—a stark contrast to the admiration that had once surrounded him.

12. The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis

In October 1809, while traveling along the Natchez Trace in Tennessee, Lewis stopped at a remote inn and was found dead from gunshot wounds. He was only 35 years old. The official report ruled his death a suicide, though some contemporaries—and later historians—suspected foul play.

The details remain uncertain, but his passing cast a dark shadow over the expedition’s legacy. The young explorer who had mapped half a continent met an end as mysterious as the wilderness he once conquered, leaving behind unfinished writings and unanswered questions.

13. The Enduring Legacy of Lewis and Clark

William Clark lived for decades after the expedition, dedicating himself to diplomacy with Native tribes and preserving the records of their journey. His maps and journals became cornerstones of American exploration history.

Together, Lewis and Clark’s expedition redefined the United States’ understanding of its land, people, and potential. Their story remains one of courage, discovery, and tragedy—a reminder that even the most celebrated triumphs can carry hidden costs, and that the drive to explore often leaves its deepest marks on those who lead the way.