Nearly 2,000 years ago, a young Roman watched Mount Vesuvius bury Pompeii—and his letters remain the only eyewitness record of the catastrophe.

When Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D., few lived to describe the horror. But a 17-year-old Roman named Pliny the Younger witnessed the disaster from across the Bay of Naples and later recorded every terrifying detail in letters to the historian Tacitus. His words paint a vivid picture of black skies, falling ash, and desperate escape—an event that claimed thousands of lives, including his uncle, Pliny the Elder. Nearly two millennia later, his haunting letters still define how the world remembers Pompeii.

1. A Clear Morning Turns to Dread

In late August of 79 A.D., life along the Bay of Naples unfolded as usual. Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Stabiae were bustling Roman resort towns, alive with merchants, artists, and families enjoying the late-summer sun. From his home in Misenum, 17-year-old Pliny the Younger admired the tranquil view across the water.

That peace ended without warning. Around midday, Pliny noticed a strange cloud rising above Mount Vesuvius. It stretched upward like a pine tree, its trunk dark and solid before branching into a wide crown. The mountain was stirring—and few grasped what it meant.

2. Pliny the Elder’s Fateful Decision

Pliny’s uncle, the renowned scholar and admiral Pliny the Elder, was immediately intrigued by the sight. A man of science and action, he ordered his ships prepared to investigate. When a message arrived from a friend trapped near the volcano, he turned his mission into a rescue.

As he sailed across the bay, ash began to fall and the air thickened with sulfur. He reassured his men, urging them forward through the darkening sky. His courage would make him a hero—but it would also lead him straight into the heart of destruction.

3. The Darkness of Noon

From Misenum, Pliny the Younger watched the sky transform. The sun dimmed until the world looked like twilight. He later wrote that the “light was gone, as if extinguished.” Ash fell like snow, coating rooftops and courtyards. The air grew so thick that people struggled to breathe.

Many ran into the streets shouting prayers, clutching pillows over their heads to ward off falling debris. The calm morning had become a suffocating nightmare. Even from miles away, the young observer could feel the terror spreading through the coastal towns below.

4. The Mountain Unleashes Its Fury

Mount Vesuvius erupted with unimaginable force, propelling ash, rock, and gas high into the atmosphere. The column soared nearly 20 miles before collapsing in fiery surges that tore down the mountain’s slopes. Thunder cracked, lightning flashed inside the dark cloud, and tremors rippled through the earth.

Pliny described the sound as “continuous and dreadful.” Roofs buckled under the weight of debris, and the sea churned violently against the shore. To those watching, it seemed as if the gods themselves were tearing the heavens apart.

5. A Terrifying View From Afar

While his uncle sailed toward the chaos, Pliny and his mother remained behind, watching from across the bay. He later described the sea “drawn backward,” exposing the seabed before crashing back in furious waves. The horizon glowed with a dull, red light as the mountain raged.

The air grew unbreathable. Ash drifted through open windows, and tremors shook the villa’s walls. From Misenum, they could hear faint screams carried by the wind. It was a nightmarish panorama—one that burned itself forever into the young Roman’s memory.

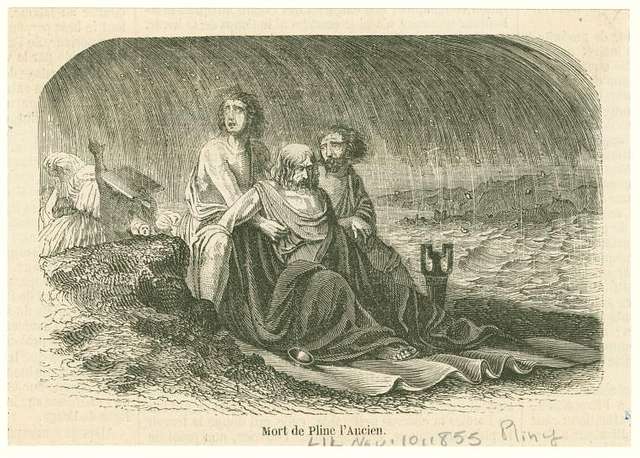

6. The Elder Pliny’s Final Moments

Meanwhile, the elder Pliny reached the town of Stabiae, where his friend Pomponianus waited. He tried to calm terrified residents, ordering them indoors as ash and pumice rained from the sky. When he lay down to rest, the fumes of sulfur and smoke overwhelmed him.

Struggling to breathe, he collapsed and never awoke. His companions later found his body near the shore, appearing peaceful, as if asleep. He had died as he lived—seeking knowledge, saving others, and facing the forces of nature with fearless curiosity.

7. The Night of Terror

By evening, a deeper darkness fell, thicker than any natural night. Pliny wrote that it felt “as though we were shut in a room with no light.” The ground quaked endlessly, walls cracked, and the air filled with shrieks. Fires burned in the distance as ash buried entire streets.

Even far from the volcano, Pliny and his mother feared the end of the world. “We heard the cries of women, the wailing of children, the shouts of men,” he wrote. “Some prayed for death in their terror of dying.”

8. Pompeii Vanishes Beneath the Ash

As the hours passed, Pompeii disappeared beneath a deluge of pumice and ash. Roofs caved in, streets vanished, and people were trapped in their homes. Superheated gases swept through the city, killing instantly and preserving bodies where they fell.

Pliny’s account captures the horror with chilling restraint. The ash fell so heavily that survivors had to constantly shake it from their clothes to avoid being buried alive. By dawn, the once-lively city had become a gray, silent tomb—a tragedy frozen in time for nearly two thousand years.

9. A Desperate Escape From Misenum

At sunrise, tremors intensified, forcing Pliny and his mother to flee their home. They joined crowds of terrified citizens moving inland, covering their heads with cloths to shield themselves from falling debris. The sea was impassable, churning violently under the storm of ash.

“The dust grew thicker and hotter,” he wrote, “and we had to keep shaking it from our clothes.” People wept openly as the earth rumbled beneath their feet. Behind them, Mount Vesuvius still burned—a monstrous column of fire and smoke blotting out the morning light.

10. The Letters That Preserved the Horror

Years later, Pliny wrote two detailed letters to the historian Tacitus, describing the eruption and his uncle’s death. These accounts became the only surviving eyewitness records of the disaster. His words combined observation with emotion, offering both a scientific and human perspective.

He described the panic, the beauty, and the devastation with remarkable clarity. Those letters would later shape how scholars understood volcanic eruptions—and how future generations imagined the final moments of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Through his pen, history survived the ash.

11. The Birth of “Plinian Eruptions”

Centuries later, volcanologists named a class of eruptions after Pliny because his description so accurately matched modern understanding. A “Plinian eruption” now refers to explosions that send towering columns of ash and gas high into the sky, exactly as he recorded in 79 A.D.

His vivid writing bridged the gap between literature and science. What he witnessed as a terrified young man became the foundation for modern volcanology. From his words, humanity learned not only the physics of an eruption but its emotional and human scale.

12. The Young Man Who Captured the End of a World

Pliny the Younger went on to become a respected lawyer, senator, and writer, yet his letters about Vesuvius remain his most famous legacy. In his youth, he bore witness to the death of cities—and the fragility of civilization itself.

Nearly two thousand years later, his words still move readers with their calm clarity and humanity. He was not merely an observer but a bridge between eras, his testimony transforming tragedy into timeless record. Through his eyes, we still see the day the sky fell over Pompeii.