Marine biologists say plastic debris in the Pacific has become home to thriving colonies of coastal species, forming a new—and uncontrollable—ocean ecosystem.

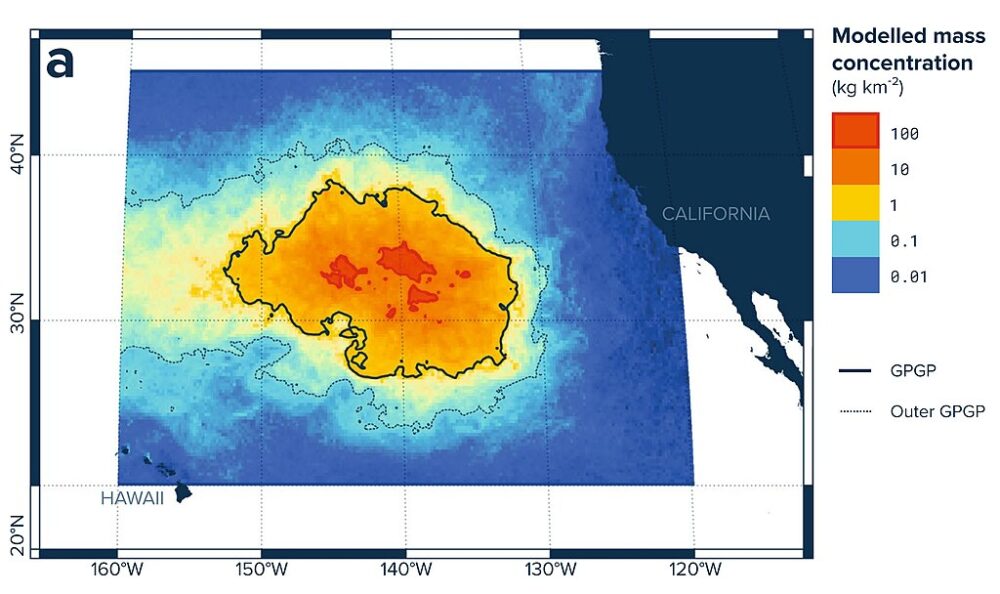

What began as a swirling mass of floating trash in the Pacific Ocean has evolved into something entirely unexpected: a living ecosystem. Recent studies show that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, now spanning more than 600,000 square miles, is hosting thriving communities of coastal organisms clinging to drifting plastic. Scientists warn this “neopelagic” ecosystem—where land-based species survive far from shore—could disrupt natural ocean food webs, spread invasive life forms, and permanently alter marine environments worldwide.

1. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch Has Become a Floating Habitat

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, located between California and Hawaii, contains an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, forming a vast swirl of debris twice the size of Texas. Once thought to be a lifeless gyre of waste, scientists have now discovered that it teems with living organisms.

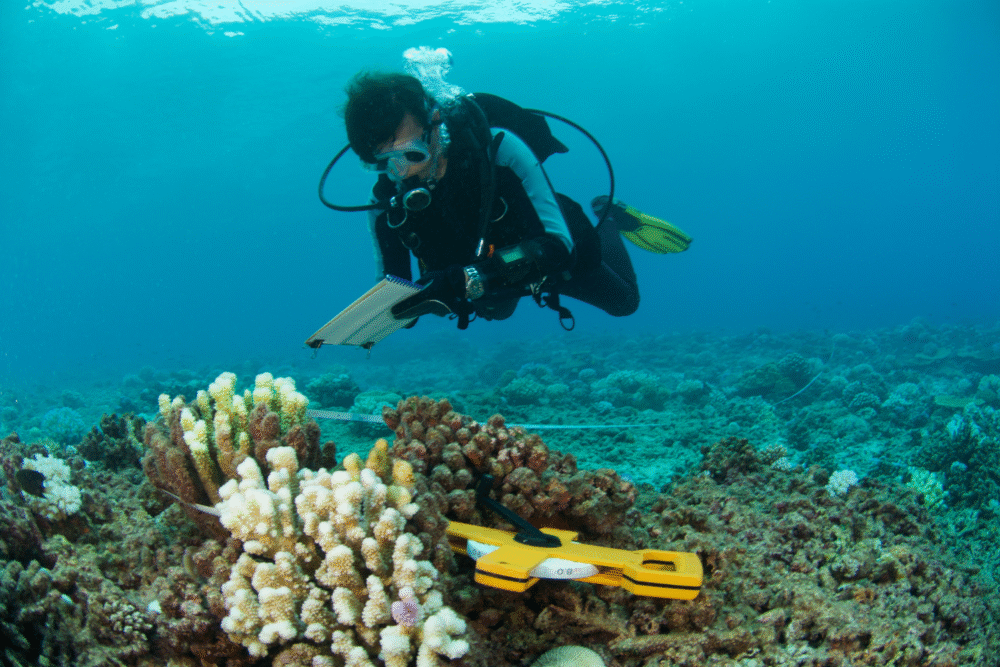

Marine biologists studying the patch found sea anemones, barnacles, crabs, and mollusks thriving on discarded plastics. These species, once confined to coastlines, are surviving thousands of miles from land—using floating trash as an artificial habitat.

2. Coastal Species Have Learned to Live in the Open Ocean

A 2023 study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution revealed that dozens of coastal species have successfully adapted to life on plastic debris drifting in the open Pacific. The organisms cling to bottles, fishing nets, and other waste that form stable surfaces.

Researchers coined the term “neopelagic community” to describe this phenomenon—coastal organisms establishing permanent colonies in the high seas. The finding challenges long-held assumptions that such species couldn’t survive in the nutrient-poor environment of the open ocean.

3. The Plastic Gyre Acts Like a Floating Island Chain

Instead of a uniform soup of microplastics, parts of the Pacific gyre have coalesced into large rafts of debris. These floating clusters function like islands, offering shelter and food sources for a variety of marine life.

Animals typically separated by vast stretches of ocean now coexist on these artificial structures. Scientists say this could change migration patterns and introduce invasive species to new environments, reshaping the delicate balance of ocean ecosystems.

4. Coastal and Ocean Species Are Competing for Space

The plastic debris has created a rare intersection between coastal and pelagic ecosystems—two biological worlds that seldom meet. On these floating rafts, coastal barnacles and crabs now compete with open-ocean species like gooseneck barnacles for food and space.

This unprecedented overlap raises concerns about how such competition might alter ocean biodiversity. Some species could outcompete others, leading to long-term disruptions in marine food webs and nutrient cycles.

5. Ocean Currents Are Spreading Life Across the Globe

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, where the garbage patch sits, circulates slowly but continuously. As debris drifts through its currents, organisms attached to plastic can travel thousands of miles from their native shores.

This mobility increases the risk of invasive species spreading across entire ocean basins. A barnacle or crab clinging to plastic from Asia, for example, could reach the North American coast within a few years, threatening local ecosystems unprepared for such arrivals.

6. The Plastic Habitat Is Expanding Faster Than It Can Be Cleaned

Despite ongoing cleanup efforts, the amount of floating plastic in the Pacific continues to grow. Ocean cleanup projects have removed thousands of tons of waste, but millions more remain—and new debris enters the ocean every day.

Researchers warn that as long as plastic pollution outpaces removal, this artificial ecosystem will continue to expand. Each new piece of debris becomes potential real estate for organisms seeking to colonize the open ocean, creating a self-sustaining cycle of growth.

7. These Plastic-Borne Species Could Disrupt Natural Ecosystems

When coastal organisms hitch rides on floating debris, they can arrive in places they were never meant to inhabit. Such introductions can devastate local species, alter habitats, and disrupt established food chains.

Marine ecologists compare the process to biological invasion on land, where non-native species overwhelm native populations. In the ocean, however, containment is far harder—there are no barriers to stop drifting life forms from spreading worldwide.

8. Cleanup Efforts May Have Unintended Consequences

Efforts by groups like The Ocean Cleanup have removed thousands of tons of plastic, but scientists caution that some debris has become essential habitat for new marine life. Removing it too quickly could destroy species now dependent on these floating ecosystems.

Balancing cleanup with ecological awareness is becoming increasingly complex. Experts suggest more research is needed to understand which debris serves as critical habitat and which poses the most immediate environmental risks.

9. Plastic Pollution Is Outpacing Marine Adaptation

Even as some species adapt to life on plastic, most marine animals are harmed by it. Sea turtles, fish, and seabirds continue to ingest microplastics, mistaking them for food. These particles can block digestive tracts, leach chemicals, and accumulate up the food chain.

Scientists stress that while life is adapting in unexpected ways, the overall effect of plastic pollution remains overwhelmingly negative. The emergence of new ecosystems doesn’t offset the damage being done to traditional marine environments.

10. A Warning About Humanity’s Impact on Evolution

The creation of an entirely new type of ecosystem—born from pollution—has profound implications for evolution. It shows that human waste can alter biology on a planetary scale, forcing species to adapt in ways nature never intended.

Experts say this “plastic-driven evolution” could become one of the most significant examples of human influence on Earth’s biosphere. It serves as both a scientific revelation and a warning: once artificial ecosystems emerge, controlling or reversing them may be impossible.