Why the Maya and other fallen empires offer surprising hope for today.

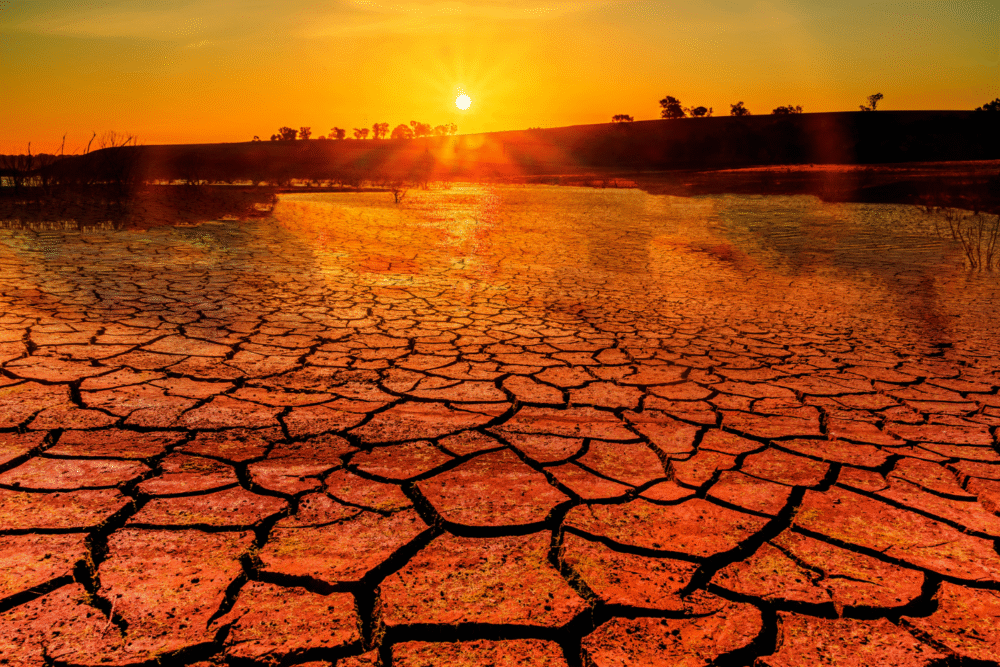

Ancient history is littered with tales of collapse—forgotten cities, devastating droughts, and entire civilizations that seemingly vanished, like the Classic Maya. We often view these apocalyptic events as terrifying cautionary tales, believing they prove humanity is fragile in the face of catastrophe. However, archaeologists studying these ruins are challenging that narrative. They see not final endings, but profound societal transformations. By examining how survivors of these dark periods adapted and reinvented their world, we find unexpected inspiration and a powerful blueprint for resilience for facing our own intertwined modern crises.

1. The Myth of the “Vanished” Civilization

We often imagine that when a great civilization like the Maya collapsed, everyone simply disappeared, lending the event a mysterious and terrifying quality. This romanticized view, however, overlooks the messy reality of survival. Collapse rarely means a population vanishes; it means their centralized political system or their elite class dissolved.

Archaeologists have shown that most people simply moved from cities to villages, adapting their lives and political structure to be smaller and more flexible. The monumental architecture stopped, but the people continued their history, proving that the end of an empire is not the end of a people.

2. Why Inequality Makes Societies Fragile

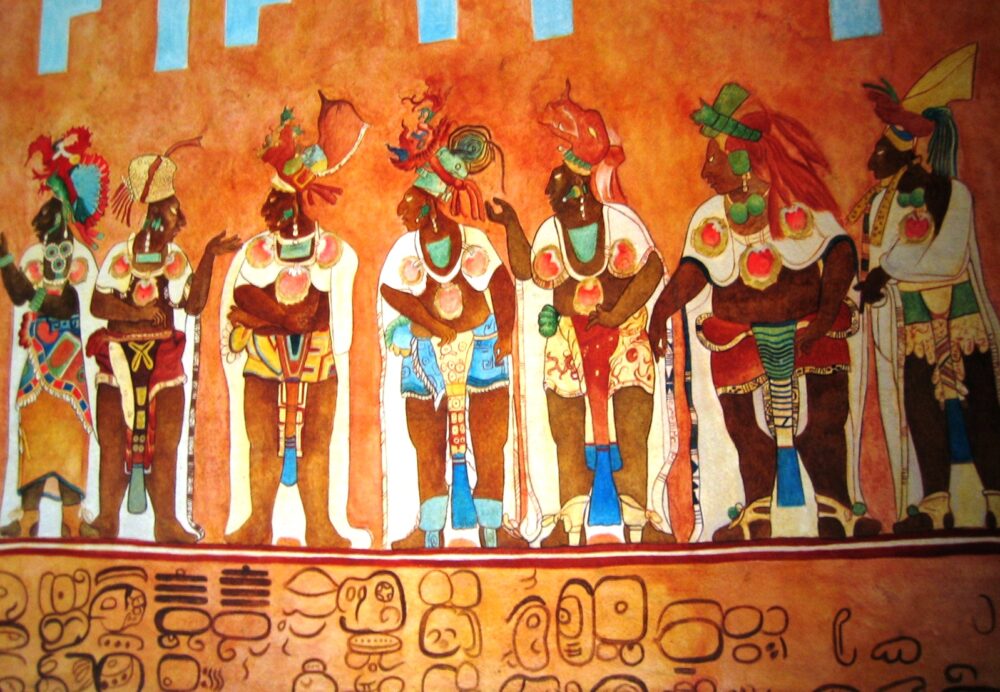

History shows that societies with extreme social stratification are the most vulnerable when apocalypse strikes. In the Maya world, the common farmers supported a massive, unwieldy elite class of divine kings and nobles. When drought hit and food supplies dwindled, the farmers couldn’t sustain the top layer.

The political system essentially became too expensive to run during a crisis. The collapse of the Maya kings was in part a popular revolution against inequality, showing that structural injustice is often the primary weakness exploited by environmental disaster.

3. The Shocking Power of Decentralization

After the collapse of the Classic Maya, survivors intentionally moved away from the complex, hierarchical system of divine kingship that had failed them. They realized that centralized power, even when seemingly strong, made them vulnerable to environmental change.

Instead, they moved into smaller, more egalitarian, and more adaptable communities. They traded monumental stone carvings for ephemeral thatched houses and localized religious practices. This deliberate shift toward flexible, less-stratified communities proved to be the most successful long-term survival strategy.

4. What Happens to Religion When the World Ends?

During apocalyptic times, the spiritual landscape of a society often changes dramatically. When the Maya kings—who were believed to be divine figures responsible for managing the weather and placating the gods—failed to stop the devastating drought, their entire religious justification crumbled.

The people didn’t stop being religious; they changed their practices. They shifted from massive public ceremonies focused on the god-kings to more personal, domestic rituals with altars in their own homes. This move shows that people abandon systems that fail them and find new ways to connect to meaning.

5. Why Catastrophe Speeds Up Innovation

While collapse is devastating, it also forces societies to drop outdated, cumbersome traditions and adopt pragmatic solutions. For instance, after the Classic Maya decline, architects stopped carving history into huge stone monuments and started building pyramids from smaller, easily accessible stones.

This wasn’t a loss of skill; it was a necessary retooling that required less labor and resources. This demonstrates that external crises accelerate the replacement of costly, symbolic methods (like glorifying god-kings) with simpler, more efficient technologies and building methods.

6. The Role of the Refugee in Societal Change

Apocalyptic times are marked by mass movement as refugees flee collapsing regions, and this movement profoundly changes the societies they enter. In the Yucatán Peninsula, people fleeing the southern Maya collapse brought instability, but also new ideas and connections.

The influx of people often forced existing communities to build walls, manage immigration, and adapt their social structures to accommodate the new population. This historical pattern confirms that migration is not just a side effect of collapse, but a major engine driving the subsequent transformation of the new world.

7. Was Warfare a Cause or a Symptom of Collapse?

In many historical apocalypses, including the Classic Maya, warfare and political instability spike dramatically just before the final collapse. It’s hard to tell if this warfare caused the collapse or was simply a desperate symptom of dwindling resources, like food and water.

Archaeological evidence in regions south of the Maya core shows cities rapidly converting into walled fortresses and evidence of attacks. In these intertwined crises, political failure, environmental stress, and warfare feed off each other, creating a chain reaction that is impossible to stop once it gains momentum.

8. The Lesson of the Second Collapse (Mayapán)

Even after learning from the disaster of divine kingship, the Postclassic Maya created the city of Mayapán, which was ruled by a confederacy—a decentralized council rather than one king. This was an attempt at shared power and stability, but it eventually failed too.

Around 1400, a drought struck again, proving that any highly centralized power, even one built on egalitarian ideals, can eventually become inflexible and unable to adapt when faced with extreme environmental challenges. The ultimate lesson is that small, local autonomy is often the most resilient form of governance.

9. The Power of Local Knowledge and Resilience

The people living in the northern part of the Yucatán Peninsula had always dealt with drier conditions than the south. They had highly developed local skills for collecting rainfall and conserving the water in their reservoirs and cenotes.

These long-developed skills were likely what helped their northern cities hold out against the severe drought for centuries longer than the cities in the south. This underscores the crucial role of local, inherited knowledge in long-term survival—it’s the foundation of resilience when global systems fail.

10. Why Apocalyptic Events Create New Identity

When a civilization’s central ideology, monumental art, and ruling class disappear, the common people lose their old identity as subjects of a god-king. This collective loss forces a fundamental shift in how they view themselves and their place in the world.

The survivors of the Maya collapse stopped defining themselves by the massive, hierarchical cities and started defining themselves through their local, flexible village life. The past wasn’t lost, but they purposefully decided to leave behind the things that had failed them, forging a brand-new cultural identity.

11. The Historical Cycle of Monumental Architecture

In the Postclassic era that followed the major collapses, the building of enormous pyramids and elaborate temples largely stopped. These costly projects, which consumed vast labor and resources, were deeply tied to the authority and prestige of the divine rulers.

The decline in monumental architecture after a collapse is a physical symbol that the entire political and religious system used to legitimize those powerful rulers has been abandoned. It proves that a “golden age” look may simply be the most fragile and unsustainable system of all.

12. Learning to Look Past the Ruins

For decades, archaeologists focused primarily on the stunning ruins of the monumental Classic cities, reinforcing the idea that Maya history ended when the buildings stopped being built. They often ignored the subtle, post-apocalyptic evidence of survivor communities.

Modern archaeology now looks for smaller, ephemeral structures—the thatched houses built on top of the old city plazas—to find evidence of the common people. This new perspective allows us to see that the collapse was not a terrifying mystery but a story of human reinvention and enduring life.