New evidence from England pushes back the timeline of deliberate fire-making by early humans by hundreds of thousands of years.

Humans mastered the ability to make fire far earlier than scientists once believed, according to a new study uncovering compelling evidence in eastern England. At a Paleolithic site near Barnham in Suffolk, researchers found heat-altered sediments, fire-cracked flint tools, and fragments of iron pyrite capable of producing sparks when struck. These clues indicate that early humans were deliberately creating and maintaining fire about 400,000 years ago, pushing back the previously accepted date by roughly 350,000 years.

1. A Landmark Discovery at the Barnham Site in England

Archaeologists working at the Barnham site in Suffolk uncovered some of the earliest evidence of deliberate fire-making ever found. The area contains baked sediments, fire-cracked tools, and traces of iron pyrite, a spark-producing mineral not native to the region. Its presence strongly suggests that early humans transported materials specifically for starting controlled fires rather than relying on natural flames.

This discovery represents a major scientific milestone. It demonstrates that early humans living in the region possessed advanced technological skills far earlier than previously documented, shifting long-held assumptions about ancient human behavior.

2. Fire-Cracked Tools and Heated Sediments Reveal Controlled Burning

Researchers identified flint tools that showed clear signs of repeated exposure to high temperatures. These fire-cracked artifacts, combined with patches of baked sediment, suggest that early humans were constructing and maintaining hearths rather than encountering scattered wildfires. The spatial pattern of burned materials indicates intentional placement and repeated activity.

This evidence challenges earlier models that portrayed early fire use as sporadic or opportunistic. Instead, it suggests that the group living at Barnham had developed consistent habits of fire-making and fire-maintenance, marking a significant step forward in technological sophistication.

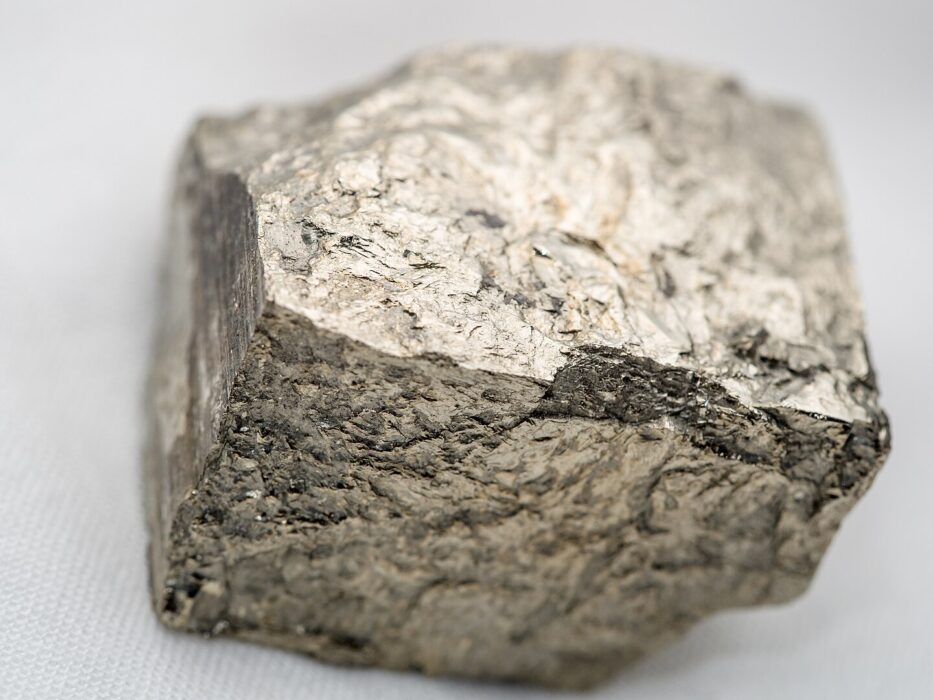

3. Iron Pyrite Fragments Point to Spark-Making Technology

Among the artifacts, researchers discovered small fragments of iron pyrite, a mineral capable of producing sparks when struck against flint. This material is rare at the site naturally, implying that early humans transported it specifically for generating fire. Such behavior indicates an understanding of fire-making techniques that go well beyond accidental ignition.

The presence of pyrite is especially significant because spark-based fire production was previously thought to be far younger. This finding suggests that early humans knew how to create fire intentionally, adding a new dimension to our understanding of early technological innovation.

4. Evidence Shows Deliberate Fire Use, Not Opportunistic Behavior

Many early archaeological sites show signs of fire, but the patterns often point to opportunistic use, such as capturing flames from wildfires. At Barnham, however, the intentional arrangement of heated materials and repeated burning indicates that fire was deliberately created and reused. These early humans were not simply preserving embers; they were actively producing flames when needed.

This discovery marks an important distinction in human evolution. Intentional fire-making reflects planning, tool use, and a deeper understanding of natural processes, all of which signal increasing cognitive and cultural complexity among early human groups.

5. Why This Discovery Dramatically Pushes Back the Timeline

Before the Barnham findings, the earliest solid evidence of fire-making dated to around 50,000 years ago. The new evidence pushes that timeline back approximately 350,000 years, representing a profound shift in how scientists understand early human technology. Heat-altered artifacts and controlled burning patterns confirm that fire production was a regular part of daily life for these ancient groups.

While humans may have used naturally occurring flames earlier, this discovery provides strong proof of intentional ignition. It reveals a much older and more sophisticated relationship between early humans and fire than previously known.

6. Early Fire-Makers Were Likely Neanderthals or Their Ancestors

Although no human bones were found at the Barnham site, the timeline and location suggest that early Neanderthals or their close ancestors were responsible for the fire-making activity. Other fossil evidence from the region shows that hominin groups with increasing brain size and tool-making abilities lived there around the same period.

This context helps researchers better understand the technological abilities of early European populations. If Neanderthals mastered fire this early, it provides new insight into their adaptability and intelligence long before their more modern behaviors were widely recognized.

7. Fire Helped Early Humans Survive Harsh Climates

Around 400,000 years ago, the climate in Britain could be cold and unpredictable, making fire a crucial survival tool. Controlled flames offered warmth, protection from predators, and extended the hours in which early humans could work or socialize. In such environments, regular fire-making would have been essential for daily life.

The ability to create fire may have allowed these early humans to expand into new and challenging regions. It provided the stability and safety needed to occupy landscapes that would otherwise be difficult to survive.

8. Cooking with Fire Transformed Early Human Diets

Fire also played a key role in shaping early human nutrition. Cooking meat and plant foods makes them easier to digest and increases the number of calories the body can absorb. This boost in available energy is linked to the development of larger brains and more physically active lifestyles.

By mastering fire early, ancient humans could access new food sources and improve overall health. The Barnham findings suggest that these dietary advantages were available far earlier than once believed, contributing to human evolutionary success.

9. Fire Likely Strengthened Social Bonds and Communication

A shared fire would have created a natural gathering place where early humans could interact, share food, and exchange knowledge. Anthropologists believe that time spent around a hearth helped strengthen group cooperation and may have played a role in the development of early communication or storytelling.

Regular fire-making suggests that these social behaviors were already forming hundreds of thousands of years earlier than previously confirmed. This paints a richer picture of early human cultural development and the role fire played in shaping it.

10. This Was Not the Earliest Fire Use — But the Earliest Ignition Evidence

Early humans may have used natural fire more than a million years ago, but clear evidence of intentional fire-making has been rare. The Barnham site provides the earliest widely accepted proof that humans were not just using fire, but actively creating it. This distinction is crucial because intentional ignition represents a much higher level of technological understanding.

The discovery helps clarify the evolutionary timeline and shows that humans were experimenting with complex fire-making techniques far earlier than researchers once believed.

11. The Findings Reshape Our Understanding of Human Evolution

The Barnham discovery forces scientists to reconsider how quickly human technology developed. Fire is a foundational tool that affects nearly every aspect of survival, from diet to migration to social behavior. Learning that humans mastered its creation so early suggests a far more advanced cognitive and cultural capacity among ancient populations.

This new perspective may influence how researchers interpret other archaeological sites. It opens the possibility that earlier examples of fire use might one day show signs of intentional ignition as well.

12. Researchers Expect Even Earlier Discoveries in the Future

Although Barnham currently holds the earliest confirmed evidence of fire-making, scientists believe older examples may exist but have not yet been found. Fire traces are fragile and can disappear over time, making them difficult to detect at ancient sites. New archaeological techniques may help uncover even earlier signs of human fire control.

Researchers plan to apply similar methods at sites across Europe, Africa, and Asia. As studies continue, more discoveries may further rewrite the timeline of when humans first mastered one of their most transformative tools.