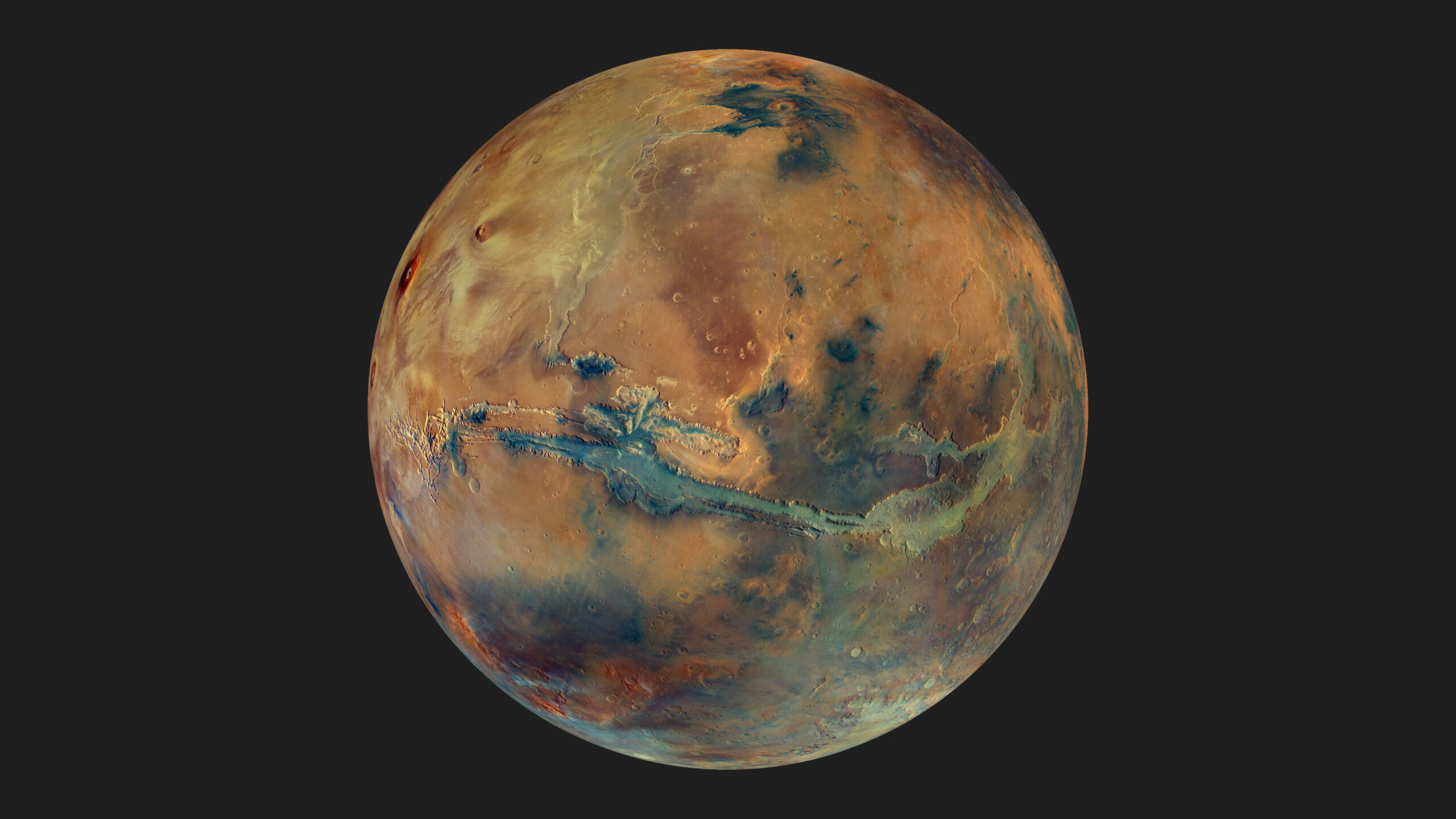

Researchers say these underground spaces could protect life from radiation and extreme cold.

If Mars ever hosted life, one of the best places to look now might be underground. Researchers led by Chunyu Ding at Shenzhen University identified eight dark “skylights” in the Hebrus Valles region that appear to open into water-carved caves.

In a peer-reviewed study, the team argues these openings aren’t volcanic lava tubes but karst-like caverns formed when water dissolved soluble rock.

That matters because caves can protect microbes—and the chemical fingerprints they leave behind—from radiation, extreme cold, and dust storms. It also gives future missions clearer targets than open desert.

Click through to learn how these caves are unique and what that means for the future of Mars exploration.

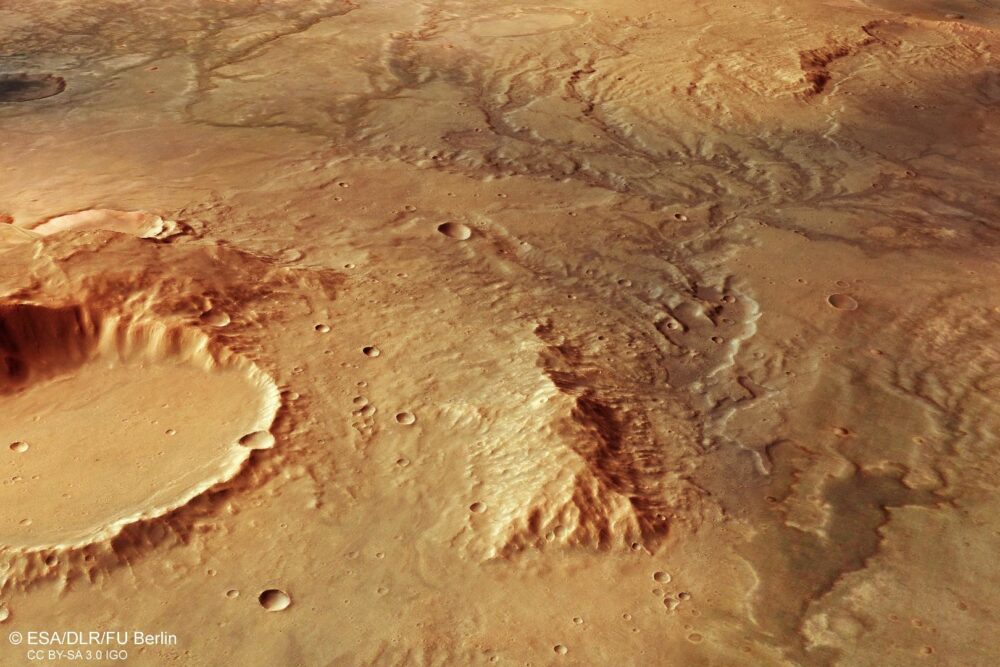

1. These caves may be a different kind of Mars cave than we’ve seen before

These features aren’t the classic Mars “cave” stories most people know. For years, many suspected underground openings were mainly lava tubes tied to volcanoes. That’s the easy explanation on a volcanic planet.

Hebrus Valles is different. The surrounding terrain shows signs of ancient water and minerals that can dissolve, making a water-built origin plausible—and more interesting for life questions down the line.

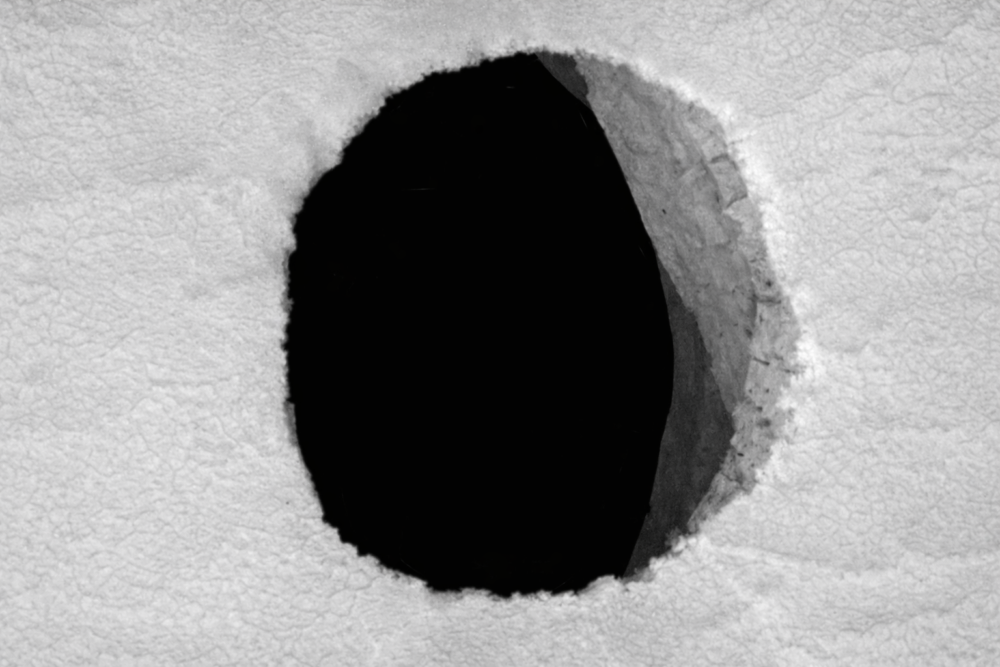

2. The “cave entrances” look like skylights rather than impact craters

From orbit, the “caves” show up as skylights—round, dark pits that look like someone punched holes in the surface. The team focused on eight that range from tens to more than 100 meters wide.

They don’t behave like impact craters. The openings lack raised rims and splashed-out debris, which hints the ground collapsed into an empty space below rather than being blasted from above. That’s a key clue.

3. The proposed origin is slow water-driven erosion, not lava flows

On Earth, karst caves form when slightly acidic water slowly dissolves soluble rock, widening cracks into chambers over long time spans. Think limestone caves, but the recipe can work with other minerals too.

In Hebrus Valles, the surrounding rocks appear rich in carbonates and sulfates—materials that water can dissolve. If ancient water moved through fractures here, it could have carved cavities that later caved in.

4. Caves matter because Mars is harsh at the surface

Mars is brutal on the surface: intense radiation, huge temperature swings, and dust that can persist for weeks. Any fragile organic molecules left in open air get broken down fast.

Underground spaces change that equation. Rock overhead can block radiation and buffer temperature extremes, creating a more stable micro-environment where chemical traces—or even dormant microbes—could last much longer.

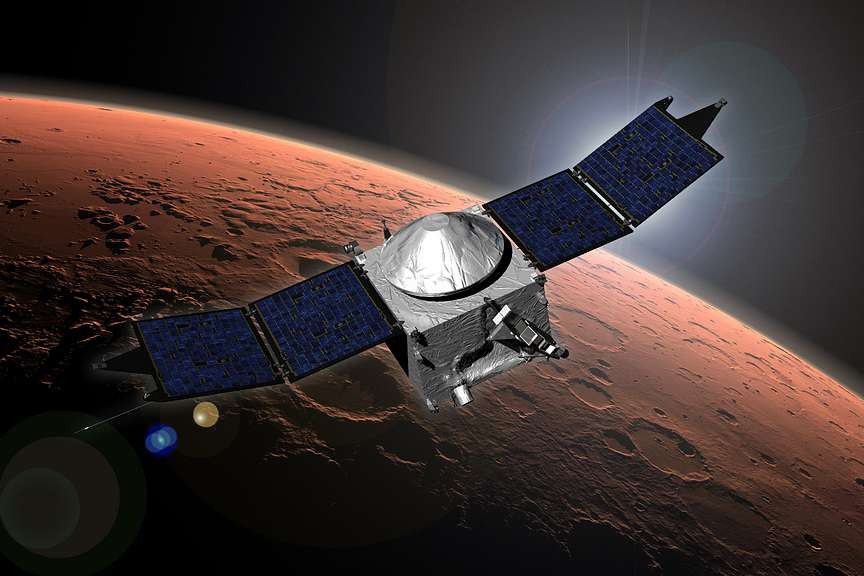

5. The evidence comes from “detective work” across multiple orbiters

The team didn’t “see” inside the caves directly. Instead, they stitched together multiple orbital datasets to build a case for what the pits likely are, and why they formed.

They compared mineral maps, hydrogen signals that can hint at buried ice, and high-resolution images used to model the pits in 3D. The shapes fit collapse into voids better than volcanic vents or tectonic cracks. It’s detective work from orbit.

6. “Accessible potential caves” is a cautious claim with big engineering implications

Calling them “accessible potential” caves is doing a lot of work. Many skylights on Mars are straight drop-offs, which is a nightmare for robots and impossible for today’s rovers.

These eight pits may include sloped debris ramps and step-like ledges, suggesting at least some could be explored with carefully designed robots. The study argues you might not need a risky free-fall into darkness every time.

Even then, caves block radio signals and create navigation problems. Future missions would likely need relays, tethered climbers, or a chain of small robots to stay connected while probing deeper.

7. The study suggests these caves should be rare, not everywhere

The research doesn’t claim Mars is riddled with these caves. Karst needs a specific recipe: soluble rocks, liquid water moving through fractures, and enough time for cavities to grow.

Hebrus Valles appears to check many boxes, including mineral deposits linked to ancient water and evidence of subsurface ice or brines. The takeaway is focused: look for similar environments, not “caves everywhere.”

8. These caves are promising targets, not proof of life

It’s important to keep expectations grounded: these pits are not proof of life, past or present. They’re “promising addresses,” not a confirmed living room.

What makes caves appealing is preservation. If microbes ever existed when Mars was wetter, sheltered spaces could have kept organic molecules from being destroyed by sunlight and radiation. That boosts the odds of finding traces that survived.

9. The next steps are confirmation first, exploration second

Right now, scientists are working with clues from above. The next step is confirmation: better imaging, improved topographic models, and radar that can help infer voids below the surface.

After that comes the hard part—getting inside. Concepts include climbing robots, tethered explorers, or small rotorcraft-style drones that can dip into skylights while relaying data back to the surface. Any mission would be built around risk management.

10. Underground targets could reshape how Mars missions choose landing sites

For decades, Mars life searches focused on ancient lakebeds, river deltas, and clay-rich rocks on the surface. Those sites are still important, but they’re exposed to harsh conditions today.

Underground targets offer a different advantage: protection. If future missions can safely reach caves, they could search for preserved biosignatures and also evaluate natural shelters that would help astronauts avoid radiation and dust.

11. The bigger story is how Mars exploration is getting more specific

What’s striking is how this discovery came from patient re-reading of old spacecraft data, not a flashy new landing. It’s a reminder that exploration is often about better questions, not just better rockets.

If these are truly water-carved caves, they expand Mars’ “habitat map” in a meaningful way. The real win is clarity: narrowing where to look, what to build, and how to test big claims with careful, step-by-step science.