Why scientists are preserving ancient ice to protect Earth’s climate record.

Deep within ice cores lie frozen records of Earth’s past climates, stored layer by layer like an atmospheric diary. As glaciers retreat, these fragile samples risk being lost forever. Scientists from around the world now collaborate to store ice cores in remote, naturally cold locations that protect them from contamination and warming. Experts from NASA and UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography emphasize that preserving these cores secures centuries of data vital to understanding climate change.

1. Ice cores contain trapped air bubbles from ancient Earth atmospheres.

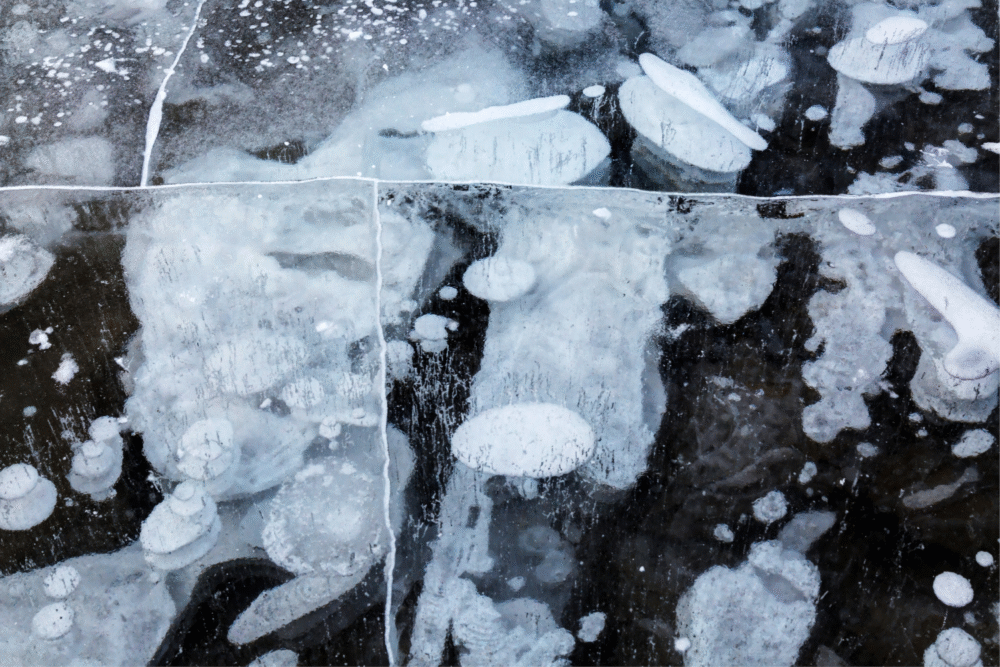

Tiny air bubbles trapped in ice cores act like time capsules from ancient atmospheres. Each layer preserves gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, offering a direct look at Earth’s evolving air over tens of thousands of years.

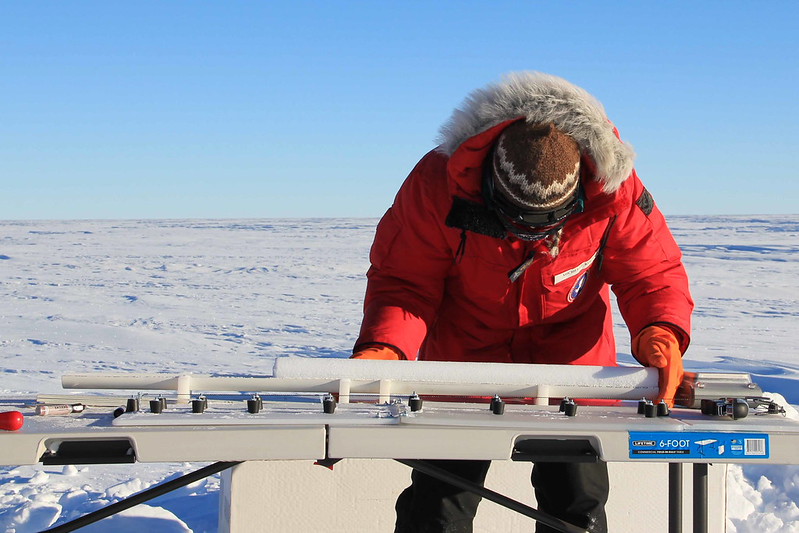

Instead of relying on inferences from tree rings or sediments, researchers can measure actual air samples sealed under pressure in compact cylinders of ice. A narrow core just four inches wide might hold annual records stretching across centuries, frozen into clear bands like a vertical ledger.

2. Preserved ice layers reveal climate shifts over thousands of years.

Frozen layers stack like pages in a geological ledger, with each year locking in snowfall, wind-blown dust, and chemical traces. Scientists read these strata to reconstruct Earth’s temperature history and shifting climate dynamics.

In one core from Antarctica, distinct ice bands have traced rapid warming periods. A sudden layer of volcanic ash might signal a past eruption, while shifts in isotope ratios map subtlest changes in ancient snowfall. The evidence stacks vertically, quietly storing ages of planetary change.

3. Scientists need untouched samples before glaciers melt any further.

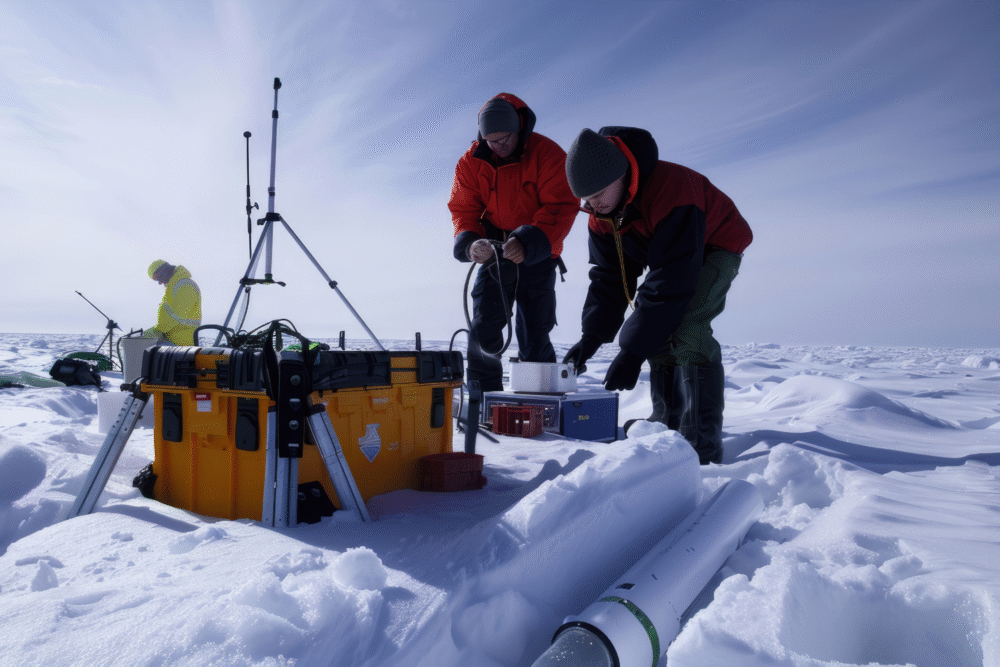

Glaciers that once expanded with steady snowfall are now retreating under the pressure of rising temperatures. That melt risks erasing irreplaceable climate records held in fragile ice, including sequences still untouched by drills.

Cores must be extracted before surface melt distorts their information or makes collection impossible. A single summer of runoff can blur decades of data in shallow layers. Researchers race to rescue ice from sites like Greenland’s interior, where warming reaches even the remote, dry plateaus.

4. Archived ice helps trace patterns in greenhouse gas concentrations.

Trapped gases and isotopes inside old ice document how greenhouse gas levels fluctuated over eras. These records help scientists understand not just the existence of warming, but its pace and triggers.

Readings from cores show that past carbon surges often matched sudden shifts in ocean currents or vegetation loss. One Antarctic core revealed a sharp methane spike linked to a rapid warming episode sixteen thousand years ago—evidence that adds weight to today’s rising trends.

5. Remote vaults protect fragile samples from modern contamination.

Modern pollutants, warmer temperatures, and microbial growth all pose risks to freshly extracted cores. Remote vaults, often dug into naturally frigid rock, insulate samples from such exposure.

One such facility sits within an abandoned Arctic mine, its tunnels chilled year-round by surrounding permafrost. There, cores remain undisturbed, preserving minute air pockets and dust layers whose structure could warp in warmer labs. Contamination, even from breath or oil, can distort the most delicate chemical readings.

6. Climate data from ice supports better models for future predictions.

Paleoclimate data from ice cores feeds into simulations that test how Earth might respond to future emissions. These cores offer long-term trends, which digital sensors—though precise—haven’t yet had time to capture.

Models that incorporate multi-century patterns from Greenland cores create more grounded predictions, adjusting for rare natural variations. Without that deep background, climate forecasts rely heavily on short-term data, limiting accuracy. The benefit of history: better foresight amid environmental uncertainty.

7. Deep ice stores evidence of volcanic eruptions and solar activity.

Beyond gases and temperature clues, deep ice cores preserve ash layers, sulfate residues, and isotopic shifts tied to solar activity. Each feature sharpens the timeline of past environmental stress.

In some layers, dense gray bands of volcanic ash stretch across thousands of miles, matching eruptions known from ancient texts. Elsewhere, subtle drops in carbon-14 levels reflect solar minima when Earth cooled. These findings bridge glaciology with astronomy, linking sky and ice to narrate global patterns.

8. Unique chemical signatures in ice reveal past ocean temperatures.

Isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen within ice reflect the temperature of the oceans that fed ancient snowstorms. Warmer oceans leave distinct molecular traces, allowing scientists to plot sea changes throughout Earth’s history.

A drop in heavy oxygen content hints at cooler water sources, while richer ratios point to warming trends. One core from West Antarctica recorded such a swing, matching coral evidence from thousands of miles away. Layers of ancient snow become thermometers etched in crystal.

9. Ice vaults provide insurance against data loss from warming trends.

As warming accelerates, so does the risk of losing valuable ice records. Vaults in cold, stable environments reduce threats from melt, theft, or accidental damage in active field labs.

By storing backup samples far from thawing zones, researchers protect an archive of global climate memory. Like rare books in secure libraries, these cores need cool, controlled conditions to remain legible. Even if glaciers vanish, their frozen records can still inform future science.

10. Stored cores allow comparison with new findings and technologies.

New tools like laser spectrometers and nano-scale scanners can examine tiny details missed by earlier equipment. Old cores, kept intact for decades, can now reveal fresh insights through modern analysis.

A single slice might uncover particles from distant dust storms or trace pollutants from centuries ago. Comparing these findings with more recent cores shows both natural cycles and human impact. Stored samples, much like film negatives, remain ready for technologies still being born.

11. The preservation effort honors decades of polar scientific research.

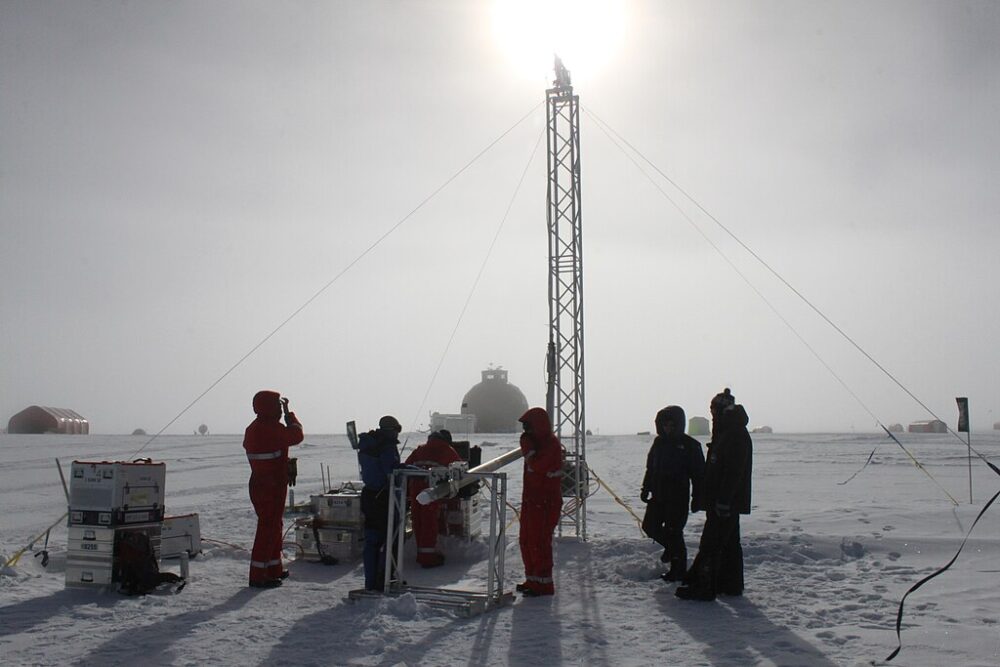

For every frozen cylinder extracted during polar expeditions, there’s a web of labor behind the scenes—decades of planning, drilling, hauling, and documentation. Preserving these samples upholds that global scientific investment.

Researchers from dozens of countries contribute to the logistics, sharing costs and findings alike. A French sample might sit beside a Japanese one in a Scandinavian vault. The archives aren’t just climate records; they’re evidence of enduring international cooperation for the sake of knowledge.