New fossils reveal a massive prehistoric shark that swam Earth’s oceans 115 million years ago.

Scientists have uncovered fossils from a gigantic prehistoric shark along the northern coast of Australia, and the discovery reveals a predator far larger than today’s great whites. The find includes five vertebrae dating back 115 million years, each more than 12 centimetres wide—significantly bigger than those of modern great whites. Researchers estimate the shark was up to eight metres long and weighed more than three tonnes. The fossils push the origins of giant lamniform sharks back by at least 15 million years, suggesting massive predatory sharks evolved much earlier than once believed.

1. Vertebrae Found Near Darwin Reveal a Monster-Sized Shark

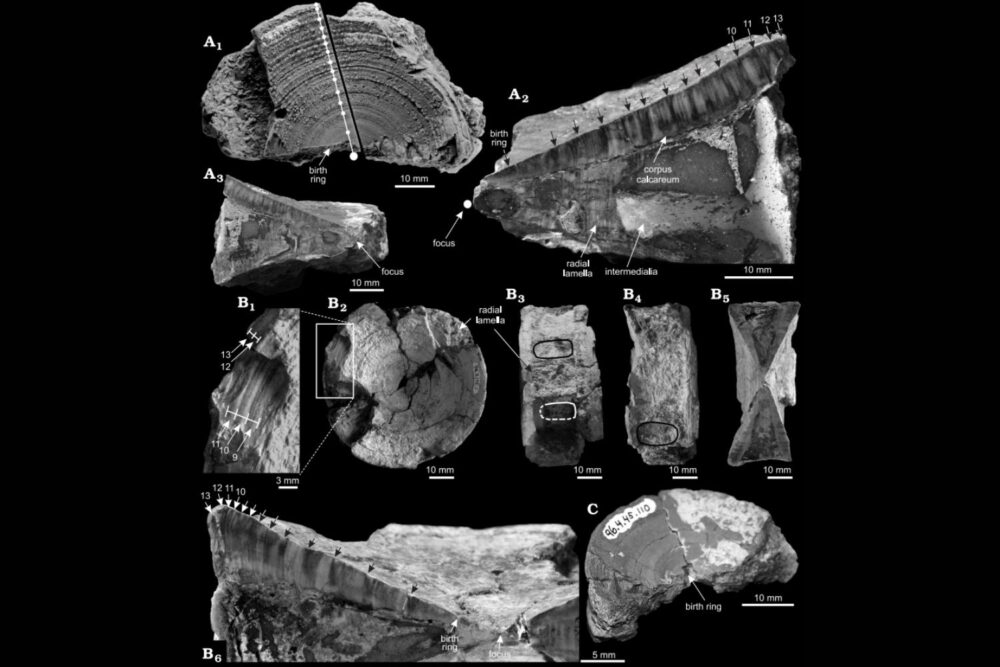

The fossils were discovered on a stretch of coastline near Darwin in Australia’s Northern Territory. Scientists identified five exceptionally large vertebrae, each dating back roughly 115 million years. Their size and shape made it clear they belonged to a massive lamniform shark, the same order as today’s great white and mako sharks.

What stood out immediately was the scale of the bones. These vertebrae were far larger than those found in any living shark species, suggesting the animal was one of the largest predators of its time.

2. The Bones Are Much Larger Than Those of Modern Great Whites

Modern great whites have vertebrae that measure about 8 centimetres across. The vertebrae from the Australian fossils were over 12 centimetres wide, making them significantly larger than the backbone structures of even the biggest great whites alive today.

This size difference allowed researchers to estimate the overall body length and mass of the prehistoric shark. The comparison makes clear that this species exceeded the dimensions of most modern marine predators, including the largest lamniform sharks known today.

3. Scientists Estimate the Shark Was Up to Eight Metres Long

Based on the vertebrae’s diameter and structure, experts believe the ancient shark measured between six and eight metres in length. Its estimated weight—more than three tonnes—places it among the largest predatory sharks known from the mid-Cretaceous period.

This size range means the shark would have been a dominant hunter in its ecosystem. Its body proportions likely resembled modern lamniform sharks, giving it speed, maneuverability and a strong bite force comparable to today’s most powerful species.

4. The Shark Likely Belonged to the Cardabiodontidae Family

Researchers think the vertebrae came from an extinct group of giant predatory sharks known as the Cardabiodontidae. These sharks once roamed global oceans roughly 100 million years ago and are known for their large size and powerful hunting abilities.

The Darwin fossils fit the anatomical profile of this family. If confirmed, they would represent one of the earliest examples of Cardabiodontidae ever found, helping fill a major gap in the shark fossil record from the mid-Cretaceous.

5. The Fossils Are 15 Million Years Older Than Any Known Relatives

One of the most surprising findings is that these vertebrae predate all previously known Cardabiodontidae fossils by around 15 million years. This pushes back the timeline for when giant sharks first evolved.

The discovery challenges earlier views that massive lamniform sharks emerged later in the Cretaceous. Instead, it appears that sharks were experimenting with extreme body sizes much earlier than scientists once believed, shedding new light on their evolutionary history.

6. The Study Suggests Giant Sharks Evolved Earlier Than Expected

Because these fossils are so much older than related species, scientists now believe that giant predatory sharks had already begun evolving large bodies by the early Cretaceous. This means the race toward gigantism among lamniform sharks started long before the rise of many later marine predators.

The findings hint that environmental pressures, abundant prey and warming seas may have encouraged early sharks to grow larger earlier than previously documented. This adds a new dimension to how researchers understand shark adaptation and diversification.

7. The Discovery Was Led by the Swedish Museum of Natural History

The study was coordinated by researchers from the Swedish Museum of Natural History, who analyzed the fossils and compared them with known shark specimens. Their work was published in the journal Communications Biology, providing the first detailed scientific description of the Darwin shark.

By examining subtle anatomical features, researchers confirmed that the fossils represent a unique and ancient form of lamniform shark, rather than an oversized individual of a known species.

8. The Fossils Offer Rare Insight Into Shark Evolution

Shark skeletons are made largely of cartilage, which rarely fossilizes well. That makes finds like these especially valuable. The vertebrae’s preservation allowed scientists to study structural traits that usually disappear in the fossil record.

Because of this, the Darwin fossils help fill evolutionary gaps between early sharks and the powerful lamniform predators that dominate today’s open oceans. Each well-preserved bone gives researchers a clearer picture of how shark anatomy developed over millions of years.

9. The Shark Lived in a Cretaceous Ocean Full of Large Prey

The shark lived roughly 115 million years ago in warm seas that supported abundant fish, marine reptiles and other shark species. Its massive size suggests it fed on large prey and played a major role in shaping the local marine food web.

This environment would have favored predators with speed, strong jaws and broad ranges—traits that appear to have already been well developed in this early giant shark lineage.

10. Scientists Expect More Discoveries Along Australia’s Coast

The coastline near Darwin is known for producing Cretaceous marine fossils, and researchers believe more remains from this shark—or related species—may still be buried in the region’s sediments. Additional discoveries could clarify how early giant sharks lived, hunted and evolved.

Future finds may also show whether this predator was part of a broader radiation of large lamniform sharks that spread across ancient oceans, or whether it represented a unique local lineage.