Experts warn that a sudden collapse in food imports could trigger humanitarian crises in vulnerable nations within weeks.

The global food system is far more fragile than most people realize. A disruption in trade—caused by conflict, climate disasters, or supply-chain collapse—could leave some nations facing severe shortages within days. According to the United Nations and the Global Food Security Index, dozens of countries depend heavily on imported grain, fertilizer, and fuel to feed their populations. If global shipping stopped tomorrow, a handful of nations would be hit hardest, exposing just how interconnected—and precarious—the world’s food supply really is.

1. Yemen faces severe risks due to heavy reliance on imported food supplies.

Yemen’s situation is precarious owing to its significant reliance on food imports. With over 80% of its food supply sourced globally, disruptions can swiftly lead to widespread shortages. The intricate network of imports means supply chain failure creates immediate and profound impacts.

Economic instability and ongoing conflict exacerbate Yemen’s vulnerability, straining the nation’s capability to secure consistent food access. With import channels at risk, food shortages can spiral into humanitarian crises, worsening already fragile living conditions. Balancing reliance with domestic production remains a critical, though challenging, task.

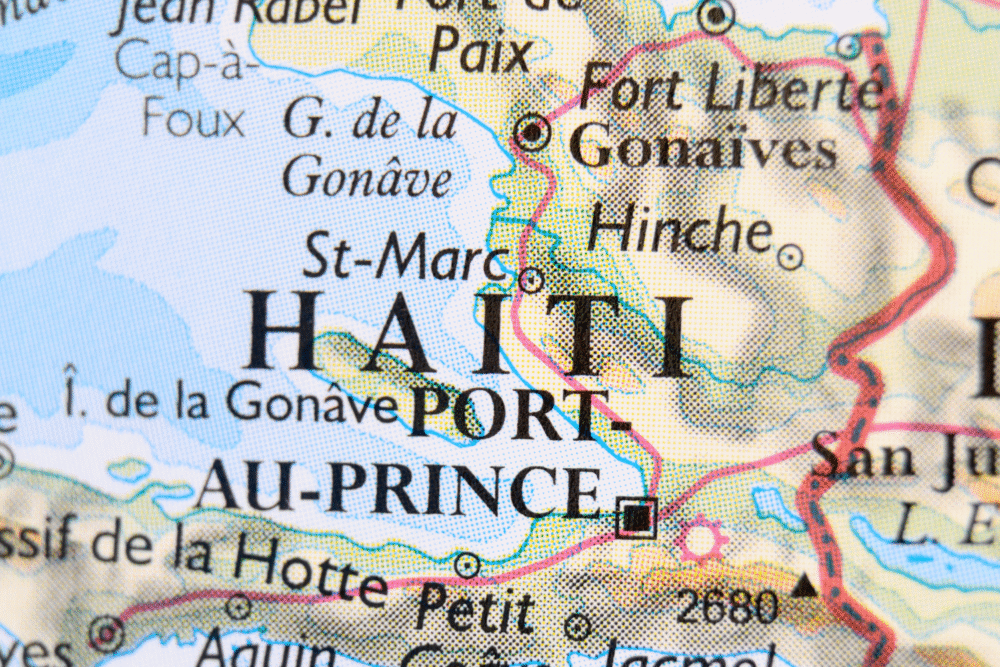

2. Haiti struggles with food insecurity amplified by fragile agricultural systems.

Food insecurity in Haiti is deeply rooted in its fragile agricultural systems. Heavy rainfall, hurricanes, and inadequate farming infrastructure severely impair local food production. These environmental challenges, coupled with limited technological advancements, weaken the country’s ability to sustain its population without relying heavily on imports.

Moreover, economic constraints further complicate food access in Haiti, making it challenging for citizens to afford imported goods. These economic hurdles, alongside erratic agricultural outputs, make Haiti particularly susceptible to disruptions in the global food supply chain, leading to acute food insecurity.

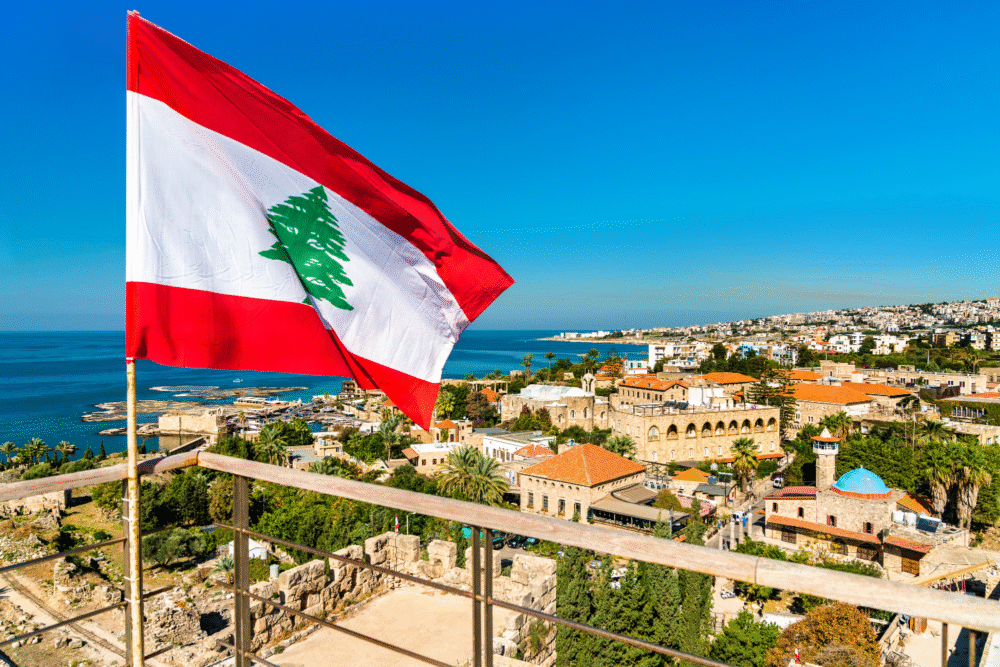

3. Lebanon depends heavily on external food sources amidst economic challenges.

Lebanon’s dependence on external food sources is palpable amid its ongoing economic struggles. With minimal domestic agricultural output, the country imports essential food items to meet local demand. Import reliance leaves Lebanon exposed to potential disruptions, increasing the risk of food supply issues.

Economic volatility in Lebanon further restricts consistent food access, as fluctuating currency values and inflation impact purchasing power. These financial hurdles intensify the effects of any global supply chain disturbances, tightening food availability and exacerbating socioeconomic tensions within the country.

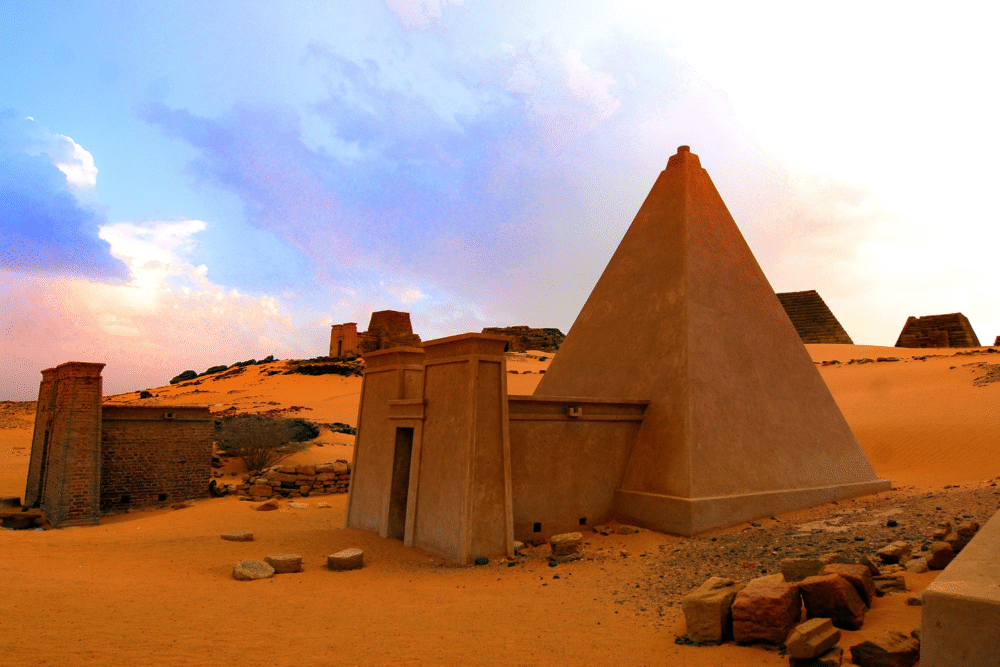

4. Sudan’s food vulnerability stems from ongoing conflicts and supply disruptions.

Sudan’s food vulnerability is heavily influenced by persistent conflicts and supply disruptions. Navigating internal strife complicates efforts to maintain stable agricultural production, limiting local capacity to achieve food security. Conflict-related disruptions disrupt supply routes, impeding efforts to distribute essential goods efficiently across regions.

Continuous conflicts exacerbate food insecurity, leaving populations in war-torn areas particularly exposed. The impacts extend beyond logistical hurdles, as insecurity often deters agricultural advancements, causing long-term challenges in overcoming food scarcity. The situation underscores the need for stabilizing factors to boost resilience.

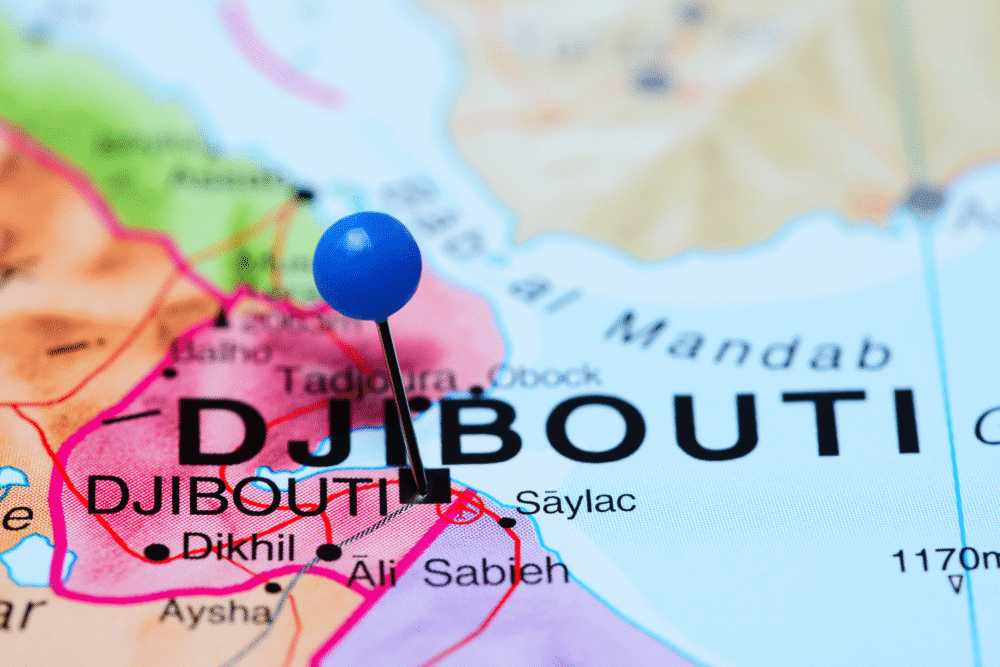

5. Djibouti imports the majority of its food, making it highly susceptible.

Djibouti’s high susceptibility to food shortages stems from its vast import needs. With over 90% of its food arriving from abroad, the country faces a high risk should global supply chains falter. Limited resources and arid conditions inhibit significant local food production.

The nation’s strategic port location amplifies its dependency, as international trade routes heavily influence import stability. Economic fluctuations and regional instability further exacerbate Djibouti’s vulnerability, highlighting the urgent need for diversified sourcing strategies to minimize impact from global trade uncertainties.

6. Somalia’s food security is threatened by frequent droughts and conflict.

Frequent droughts and ongoing conflict threaten food security in Somalia, a nation already struggling with inconsistent agricultural yields. These environmental and political challenges severely hinder farming efforts, making the population heavily reliant on global food imports to meet basic nutritional needs.

Further complicating matters, logistical challenges from conflict zones often disrupt food distribution networks. This raises the likelihood of acute food shortages as disrupted imports create persistent access barriers. Economic insecurity further deepens these vulnerabilities, calling for resilient strategies to address food supply instability.

7. Papua New Guinea relies on food imports despite agricultural potential challenges.

Despite its agricultural potential, Papua New Guinea relies significantly on food imports. Challenging terrain and limited infrastructure hinder efficient local food production, resulting in a dependence on external sources. With imports covering dietary staples, withdrawal from international supply can lead to substantial shortages.

Simultaneously, opportunities to bolster domestic agriculture face hurdles due to remoteness and diverse ecosystems. Addressing these constraints while navigating global trade dynamics plays a critical role in improving food security, as constrained domestic output struggles to meet the growing population’s needs effectively.

8. Central African Republic suffers from infrastructure issues impacting food access.

Infrastructure issues in the Central African Republic (CAR) significantly impair food access. With inadequate roads and transport networks, moving food supplies across regions is challenging, impacting timely distribution. These logistical constraints are compounded by limited domestic agricultural output, making imported goods vital.

Such infrastructural inadequacies lead to disparate food availability across CAR, exposing rural communities to heightened risks of shortages. Economic instability further restricts buying capacity, emphasizing the need to enhance infrastructure to facilitate consistent and equitable food access across the landlocked nation.

9. Liberia’s limited domestic food production increases vulnerability to supply shocks.

In Liberia, limited domestic food production heightens its vulnerability to global supply shocks. The country’s agriculture sector struggles with outdated techniques and inconsistent yields, relying on imports to fill dietary needs. Any disruption in international trade threatens to create immediate shortages and price surges.

Economic considerations further complicate the situation, as these imports strain national finances. Limited financial resources restrict sustainable agricultural investments, underlying the need for innovative solutions to reduce dependency, stabilize food stocks, and enhance local capacity for better food security resilience.

10. Comoros depends on external food chains due to small landmass and resources.

Comoros, with its small landmass, depends heavily on external food chains. Limited arable land and scarce natural resources intensify this reliance, forcing the island nation to import most food essentials. Any fluctuations in these supply chains can cause cascading effects on food availability.

Economic challenges further strain Comoros’ ability to cope with supply chain disruptions. Price changes in imported goods directly affect affordability, making balanced nutrition difficult to maintain. As global market pressures rise, the need for strategic sourcing and diversification becomes more crucial to support food security.