Archaeologists reveal the complex truth about care, neglect, and survival in the empire.

It’s a common—and frankly, chilling—idea: that Romans were so focused on strength, they simply left anyone with a disability to die. Ancient sources hint at this brutality, suggesting that infants with visible differences were exposed. But what does the hard archaeological evidence actually show us? Turns out, the real story is much more complicated. New discoveries from Roman sites are rewriting this narrative, revealing a surprising mix of cruelty, survival, and even compassion that shaped the lives of disabled people across the mighty empire.

1. Did the Romans Really Abandon “Defective” Babies?

The most notorious example of Roman cruelty involves infanticide, or more specifically, exposure. Ancient texts often describe how a father had the legal right to reject a newborn if it appeared weak or “monstrous.” This baby would then be left exposed to the elements to die. While the practice was certainly cruel by modern standards, it was legal and rooted in the intense pressure of Roman family structure and patriarchy.

However, recent archaeological findings challenge the idea that this was a constant, widespread purge of all disabled infants. Discoveries of mass infant graves don’t always show a selection based on physical disability. Moreover, the act of “exposure” sometimes included a chance for the child to be rescued and raised as a slave or adopted, complicating the simple narrative of cold-hearted abandonment.

2. The Myth of the “Perfect” Roman Body

It’s often assumed that the Romans, obsessed with athletic strength and military prowess, held a strict ideal of the perfect body, leading them to cast out anyone who didn’t meet that standard. While physical fitness was certainly prized, the reality was far messier. The empire was massive, encompassing legions of people with injuries, chronic illnesses, and congenital conditions.

The Roman world was full of successful citizens who lived with long-term disabilities. Emperors themselves, like Claudius, had physical impairments. Being a soldier wasn’t the only way to contribute. Skilled artisans, teachers, and bureaucrats thrived, and their value often lay in their specialized talents, not their physical perfection.

3. Who Was Really Cared for and Who Was Cast Out?

The dividing line between who received care and who was left to suffer was rarely about disability itself; it was about status and wealth. A disabled child born to a wealthy, powerful family would likely receive the best available medical treatment and lifelong support from their household, tutors, and specialized staff. Their survival was tied to their family’s resources.

Conversely, a poor or enslaved person with a similar condition had little hope for extensive care. Their survival depended on their productivity or the generosity of their immediate community. This huge disparity meant that disability was primarily a crisis of class, making care and neglect highly inconsistent across the Roman Empire.

4. Were There Roman Hospitals for the Sick?

The modern concept of a public hospital where anyone could seek aid did not exist in ancient Rome. However, specialized medical facilities certainly did. The most common facility was the valetudinaria, which was essentially a military hospital built specifically to treat wounded or sick soldiers. These were highly organized and professional, showing a clear commitment to rehabilitation for the state’s military assets.

For the general public, care mostly took place in the home or through private practitioners. There were also religious healing centers, like the temple of Asclepius, where people with chronic illnesses sought spiritual and practical aid. While not “hospitals” as we know them, these centers show that a structure existed to address severe medical need.

5. The Unexpected Survival of the Severely Disabled

Archaeological evidence from Roman cemeteries is proving to be a game-changer. Skeletons have been found showing evidence of severe, long-term conditions—such as crippling childhood polio, healed amputations, and debilitating joint diseases—that required profound, sustained care to manage. These individuals clearly lived into adulthood, sometimes for many years.

This physical evidence strongly suggests that someone was feeding, bathing, and supporting these people for decades. This challenges the simple idea of mass abandonment, indicating that family loyalty, duty to clients, or communal charity often superseded the theoretical right to exposure or neglect.

6. What Happened to Wounded Roman Soldiers?

The Roman army wasn’t built to discard valuable, trained manpower. Soldiers who suffered career-ending injuries weren’t simply thrown out; they were often given a missio causaria (honorable discharge due to medical reasons). This included a severance package, sometimes a parcel of land, and usually Roman citizenship if they didn’t already have it.

While their life changed dramatically, they were provided for, showing the state’s interest in taking care of its veterans. These disabled veterans would then often settle in colonies, becoming valuable members of new communities, proving that disability didn’t automatically mean destitution or exclusion, at least not for the military class.

7. Disability and Roman Law: No Protection?

Roman law did not recognize “disability rights” as we understand them today. However, it did make accommodations for those with impairments. For instance, a person who was deaf or mute might be prevented from making a will in certain ways, not out of cruelty, but because legal processes required specific spoken declarations or witnesses.

Conversely, laws regarding inheritance and guardianship often included provisions to protect the property and interests of those deemed physically or mentally incapable of managing their own affairs. This highlights that while the law could be limiting, it also had mechanisms intended for protection and guardianship, showing a complex legal relationship with impairment.

8. How Did Romans View Blindness and Deafness?

Sensory impairments carried cultural baggage. A blind person was sometimes viewed as being closer to the gods or possessing prophetic wisdom, an idea that appears in Greek and Roman mythology. On the other hand, being deaf or mute was often equated with intellectual impairment due to the close link between speech and legal competency.

Despite these stereotypes, everyday life dictated a more pragmatic approach. We have evidence of deaf individuals inscribe epitaphs, suggesting forms of communication existed, and blind people are known to have held positions as poets or diviners. Their status ultimately depended more on their class and individual talents than on the impairment itself.

9. Did Rome Care for Mental Health Issues?

The Romans had no real concept of mental illness as a medical condition; distress was often attributed to supernatural causes, melancholy, or a fundamental imbalance. Individuals exhibiting what we now call severe mental illness were typically cared for by their families, who had full authority over their fate.

The primary legal action regarding mental impairment involved the curator furiosi—a guardian appointed to protect the assets of someone deemed unable to manage their own property. While there were no clinics dedicated to psychiatric care, the legal system focused on safeguarding the person’s wealth, ensuring their basic needs could still be met through their estate.

10. Tools and Tech: Roman Accessibility

While the Romans didn’t have sophisticated wheelchairs, they were certainly resourceful. Archaeological finds show evidence of specialized equipment, such as unique wooden walking sticks or even simple prosthetic devices, like the famous Capua Leg . Ramps, while often installed for moving goods, also made access easier in public buildings and temples.

However, accessibility wasn’t a priority driven by social policy. Any architectural accessibility was usually a fortunate side effect of engineering for trade or the movement of war machines. The existence of personal tools, though, proves that disabled Romans found ways to adapt and function within their society.

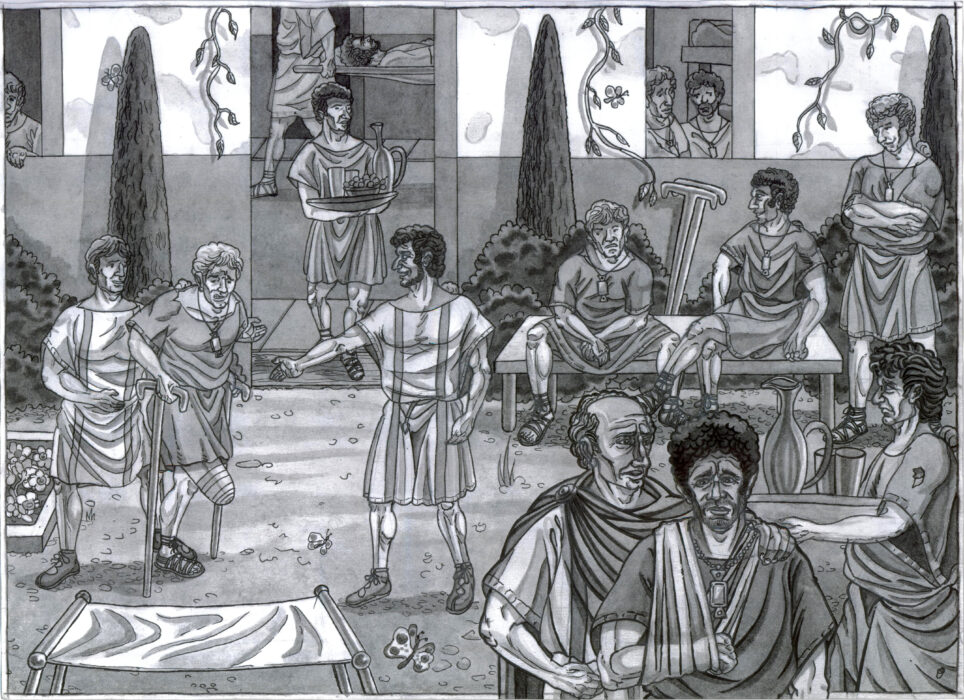

11. The Role of Charity and Private Kindness

Outside of the law and military structures, private charity and individual kindness played a major role in the survival of many disabled people. Patrons often offered support to their clients, and evidence of religious charity, particularly as Christianity began to spread, included provisions for the sick and poor.

This personalized, domestic, and often ad-hoc care system means that the fate of a disabled Roman ultimately rested heavily on the ethical values and financial means of their immediate family and community. This mixed record shows that Roman policy was never a single, monolithic rule of abandonment.