Experts warn faster growth could shorten tree lifespans and disrupt carbon storage.

Scientists studying the Amazon rainforest have discovered that rising carbon dioxide levels and warmer temperatures are making trees grow faster and larger than before. Published in Nature, the research analyzed decades of growth data and satellite imagery across the Amazon Basin. While the accelerated growth might sound like good news for carbon absorption, experts warn that it comes with serious risks. Faster-growing trees tend to die younger, potentially undermining the rainforest’s ability to store carbon and stabilize the global climate.

1. Rising CO₂ Levels Are Fueling Faster Growth

Plants absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, using it to build biomass. As atmospheric CO₂ levels rise, trees in the Amazon now have more of this “fuel” available, which has led to faster growth rates across vast regions.

Researchers found that this fertilization effect is especially noticeable in young and mid-sized trees, which are expanding their canopies more quickly than in past decades. However, scientists say this rapid expansion may not translate into long-term stability for the forest ecosystem.

2. Larger Trees May Die Younger

While trees are growing faster, they may also be living shorter lives. Rapid growth can strain a tree’s internal structure, leaving it more vulnerable to drought, disease, and mechanical stress.

Studies show that fast-growing trees develop wood that is less dense and more prone to decay. In the long run, this could mean that the Amazon’s ability to store carbon weakens as older, slower-growing giants die off and are replaced by less durable trees.

3. Droughts Are Offsetting the Growth Gains

In recent decades, the Amazon has experienced increasingly frequent and severe droughts driven by global warming. These dry periods counteract the CO₂ growth boost by causing tree stress and mortality.

Researchers found that during El Niño years, when rainfall drops sharply, the overall carbon gain from faster growth can vanish. Trees that have expanded quickly are often the first to die in prolonged drought, turning short-term growth into long-term carbon loss.

4. The Amazon’s Carbon Sink Is Weakening

For decades, the Amazon acted as one of the world’s largest carbon sinks, absorbing roughly 5% of global annual CO₂ emissions. But recent studies show that this capacity is declining.

As fast-growing trees die sooner, the carbon they stored is released back into the atmosphere. In some areas, especially the southeastern Amazon, forests are emitting nearly as much carbon as they absorb, suggesting the region may be approaching a dangerous tipping point.

5. Tree Mortality Is Rising Across the Basin

Field surveys across hundreds of Amazon research plots reveal that tree mortality rates have increased by about 30% over the past four decades. Scientists link this to a combination of faster growth, heat stress, and drought conditions.

This trend is changing the forest’s age structure. Mature, carbon-dense trees are dying off more quickly, while younger trees—though more numerous—store less carbon overall. The forest may appear greener from above, but its ecological balance is deteriorating below the canopy.

6. Climate Change Is Shifting Tree Composition

Not all trees are responding to climate change in the same way. Some species, particularly fast-growing ones, are thriving, while others adapted to cooler, wetter conditions are declining.

This shift could permanently alter the makeup of the Amazon rainforest. As fast-growing, short-lived species dominate, the forest’s diversity and resilience decrease. Scientists warn that these compositional changes could make the Amazon more vulnerable to future climate shocks and deforestation pressures.

7. Heat Stress Is Taking a Hidden Toll

In addition to drought, rising temperatures are directly damaging tree physiology. When air temperatures climb above 35°C (95°F), photosynthesis slows or stops altogether, even in heat-adapted species.

The combination of heat and reduced rainfall can cause widespread canopy dieback. Large trees, which require more water to sustain their height and leaf area, are particularly at risk. Even though the forest may temporarily appear lush, it’s operating under increasing thermal stress.

8. Bigger Trees Don’t Always Mean More Carbon Storage

Although individual trees are getting larger, their rapid turnover means the total carbon stored in the ecosystem may not increase. When trees die, their decomposing wood releases carbon back into the atmosphere.

If mortality rates continue to climb, the Amazon could transition from a carbon sink to a carbon source. That shift would accelerate global warming and weaken one of Earth’s most vital climate-regulating systems.

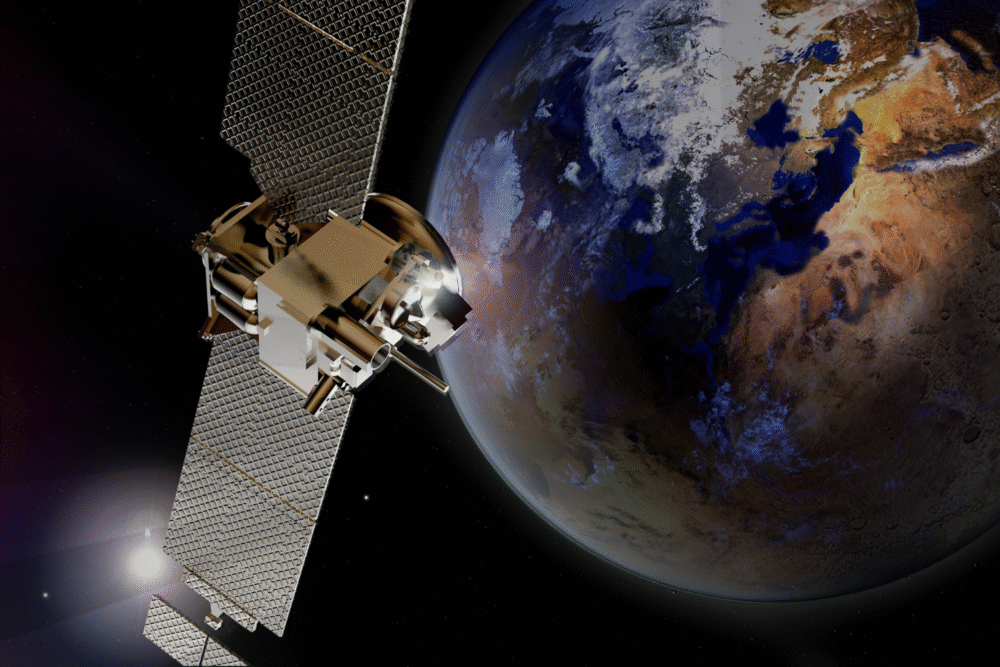

9. Satellite Data Confirms the Trend

Researchers used decades of satellite imagery to measure canopy height and density across the Amazon. They found that average tree height has increased in several regions, consistent with ground-based growth measurements.

However, the same data show expanding patches of tree mortality and canopy loss in areas affected by heat and drought. This mixed pattern suggests the forest is both growing and dying faster—a dynamic equilibrium that may be increasingly unstable.

10. The Growth Surge Could Mask Ecological Decline

From a distance, the Amazon may look greener and more vibrant than ever. But scientists caution that rapid growth can hide deeper ecological problems. Short-lived trees dominate areas where slow, hardwood species once stood.

This creates what researchers call “ephemeral biomass”—a forest that grows quickly but loses resilience. Without long-lived trees to anchor its structure, the Amazon could become more susceptible to wind damage, fire, and deforestation.

11. What It Means for the Future of the Amazon

The discovery that climate change is accelerating tree growth is a reminder that not all environmental change is straightforwardly positive. While faster growth briefly enhances carbon uptake, it also increases instability in one of Earth’s most important ecosystems.

Scientists say the long-term outcome will depend on how the forest adapts to ongoing warming and deforestation. Protecting mature, slow-growing trees and reducing greenhouse gas emissions are critical steps to prevent the Amazon from shifting from a carbon buffer to a carbon source.