A newly sequenced genome reveals a completely isolated Neanderthal population that never mixed with humans or other groups.

Researchers working on the study “Long Genetic and Social Isolation in Neanderthals Before and During Their Extinction,” published in Cell Genomics, have sequenced the genome of a 42,000-year-old Neanderthal whose DNA shows no evidence of interbreeding with modern humans or even with other Neanderthal groups. The individual appears to have belonged to a small, isolated population. The findings offer rare insight into how fragmented Neanderthal communities were near the end of their existence and what that isolation may reveal about their decline.

1. A Newly Sequenced Genome Reveals a Completely Isolated Neanderthal

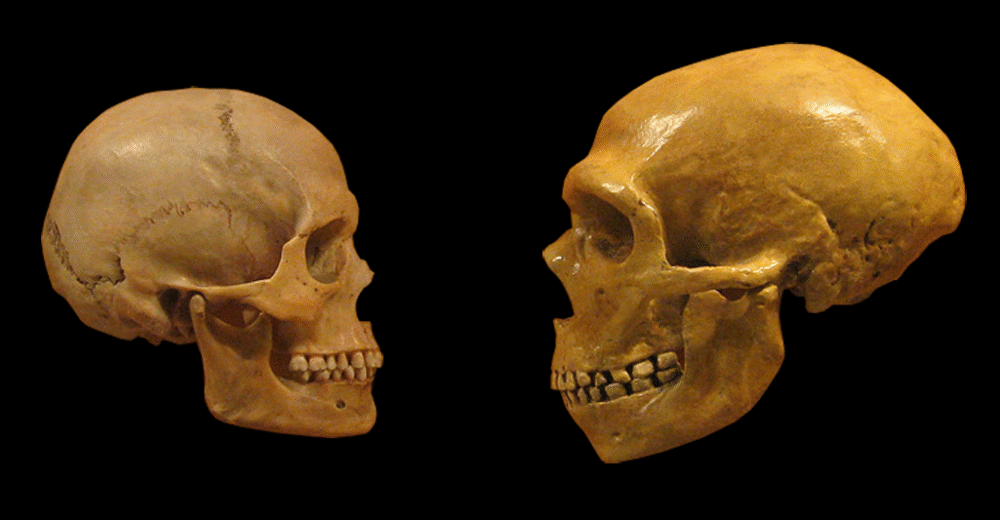

Scientists sequenced the DNA of a 42,000-year-old Neanderthal found in France and discovered he belonged to a genetically isolated group. Unlike many other Neanderthals, his genome showed no signs of mixing with modern humans or even with neighboring Neanderthal populations. This makes him one of the most genetically distinct Neanderthals ever studied.

The findings suggest his community lived separately for thousands of years, cut off from other groups across Europe. This rare level of isolation provides a clearer picture of how fragmented Neanderthal populations were near the end of their existence.

2. The Study Suggests Neanderthals Were More Diverse Than Once Thought

Published in Cell Genomics, the research shows that Neanderthals were not a single connected population. Instead, different groups lived in separate regions, each with its own genetic history. The newly sequenced individual represents one of these isolated lineages, highlighting unexpectedly high variation among Neanderthal groups.

This diversity helps explain why earlier Neanderthal genomes sometimes showed conflicting patterns. By sequencing more individuals from different regions, scientists are learning that Neanderthals may have been far more diverse—in culture and genetics—than previously believed.

3. They Lived Near the End of Neanderthal History

The Neanderthal in the study lived about 42,000 years ago, a time when Neanderthal populations were shrinking. His genome offers a rare glimpse into the final stages of Neanderthal existence and how scattered their communities had become. Many groups had already disappeared as climates shifted and resources changed.

Understanding what life looked like during this late period helps scientists study how isolated pockets of Neanderthals survived. It also provides clues about why some groups collapsed earlier than others, contributing to the species’ eventual disappearance.

4. No Evidence of Interbreeding Appeared in His DNA

Most previously sequenced Neanderthals show some degree of interbreeding—either with modern humans or with other Neanderthal groups. This individual, however, showed none. His genome lacked the genetic markers typically associated with these interactions, indicating total genetic separation.

This discovery challenges assumptions that most Neanderthals regularly interacted with outsiders. Instead, it suggests that some groups lived in almost complete isolation, rarely encountering other populations. This level of separation may have shaped how these communities developed and survived.

5. The Genome Shows Signs of Inbreeding From a Small Population

Genetic analysis revealed unusually high homozygosity, meaning this Neanderthal’s parents were closely related. This pattern is often seen in populations with limited numbers of individuals and few options for mates. Such small community sizes can reduce genetic diversity and increase health risks over generations.

The finding supports theories that shrinking population sizes weakened many Neanderthal groups. Without enough genetic exchange, isolated groups became more vulnerable to sudden environmental changes, disease, and food shortages—factors that may have hastened their decline.

6. Archaeological Evidence Shows This Group Had Unique Cultural Traits

Alongside the DNA, researchers examined stone tools and animal remains from the site. These materials suggest the group had distinct hunting strategies and tool-making techniques that set them apart from other Neanderthals. Their daily practices reflect a culture shaped by local resources and environmental pressures.

This combination of genetic and archaeological evidence shows that isolated communities developed unique traits. Studying these patterns helps researchers understand how different Neanderthal groups adapted to their surroundings and how cultural diversity emerged across regions.

7. Isolation May Have Increased This Group’s Vulnerability

Small, separated populations often struggle to survive long-term. With fewer individuals, each loss has a greater effect on the entire group. Genetic isolation also reduces resilience to disease, climate change, and difficult hunting conditions—all challenges Neanderthals regularly faced.

This individual’s genome suggests his community may have already been in decline before Neanderthals disappeared entirely. Their isolation could have made it harder for them to recover from hardships, contributing to the species’ gradual extinction.

8. The Findings Challenge Ideas About Neanderthal Movement

Earlier theories suggested Neanderthals moved widely across Europe and interacted frequently with other groups. This genome tells a different story. Some communities may have stayed in one region for thousands of years, rarely traveling far beyond their territory.

This limited mobility would have restricted opportunities for genetic exchange, reinforcing their isolation. Recognizing these differences in movement patterns helps scientists understand why some Neanderthal groups were more connected while others remained separate.

9. The Research Helps Explain Why Neanderthal DNA in Humans Is Limited

Today, modern humans carry only about one to two percent Neanderthal DNA. If many Neanderthal groups were isolated, only a few populations likely interacted with early humans at all. That means most Neanderthal lineages—including the one in this study—left no genetic trace in living people.

This new understanding helps scientists identify which groups contributed to the human gene pool. It also explains why modern human DNA contains only small fragments from a limited number of Neanderthal ancestors.

10. Advanced DNA Technology Made This Discovery Possible

Sequencing a genome that is more than 40,000 years old requires cutting-edge techniques. Scientists had to extract and analyze extremely fragile DNA fragments preserved in bone. Improvements in ancient DNA methods now allow researchers to recover far more information than was possible even a decade ago.

These technological advancements are transforming the study of human evolution. Each newly sequenced genome adds another piece to the puzzle, revealing details about ancient populations that were once impossible to uncover.

11. This Discovery Adds Depth to the Story of Human Origins

Rather than presenting a simple narrative, the new genome highlights the complexity of Neanderthal history. It shows that different groups lived very different lives, shaped by geography, climate, and cultural practices. Understanding this diversity helps scientists build a more accurate picture of how ancient humans and Neanderthals coexisted.

The study reminds us that human evolution wasn’t the story of a single population but of many interacting—or in this case, isolated—groups. As more genomes are sequenced, researchers will continue to refine and expand our understanding of our shared past.