New calculations suggest the universe’s “end date” may be far sooner than scientists once estimated.

The universe isn’t ending tomorrow, but scientists are still arguing about its ultimate expiration date. For decades, the far-future story focused on black holes slowly evaporating over an almost unimaginable timescale.

Now a new line of research suggests the countdown might be shorter—not because the universe is in danger, but because more things may “evaporate” over time than we realized.

It’s still a number with dozens of zeros. But the shift changes how we picture the very last chapter of everything.

1. The “end of the universe” is really a question of timescales

When scientists talk about the universe ending, they usually mean it becomes cold, dark, and spread out—so empty that complex structures can’t survive. It’s not a single explosion, more like a slow fade.

The key question is how long the fade takes. Different assumptions about physics change the timeline dramatically, so “end date” often depends on which cosmic ingredients you include and which theories you trust most.

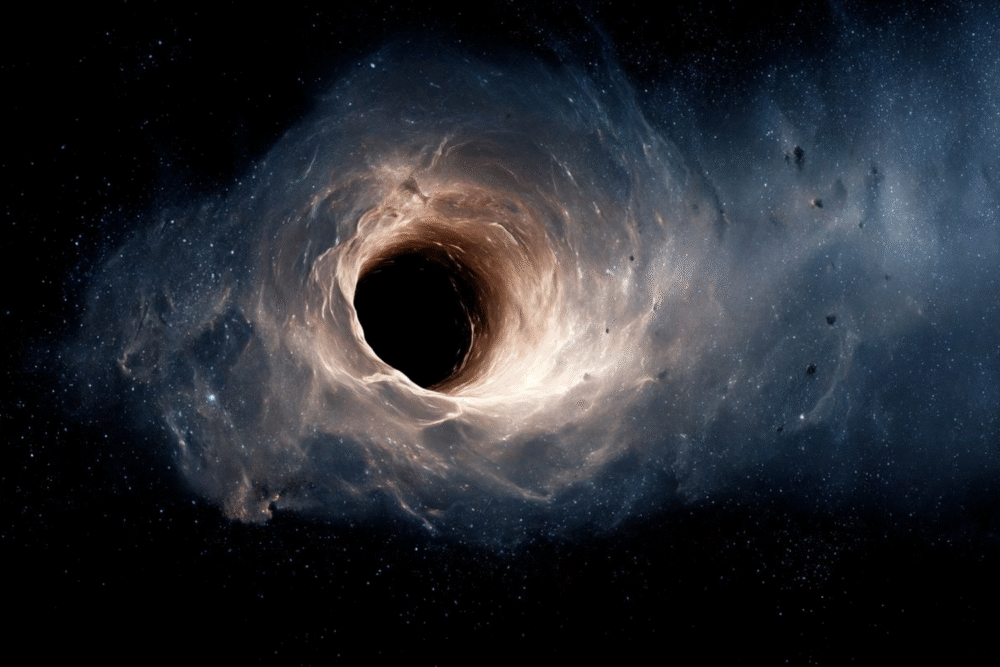

2. For a long time, black holes were the main clock

Stephen Hawking’s famous idea says black holes aren’t eternal. Over extreme time, they should emit radiation and slowly lose mass until they disappear.

Because the biggest black holes can take staggeringly long to evaporate, they became the standard “last survivors.” The usual picture was a long Black Hole Era, followed by an even darker universe once those final giants finally wink out.

3. The new twist: maybe everything dense can evaporate, too

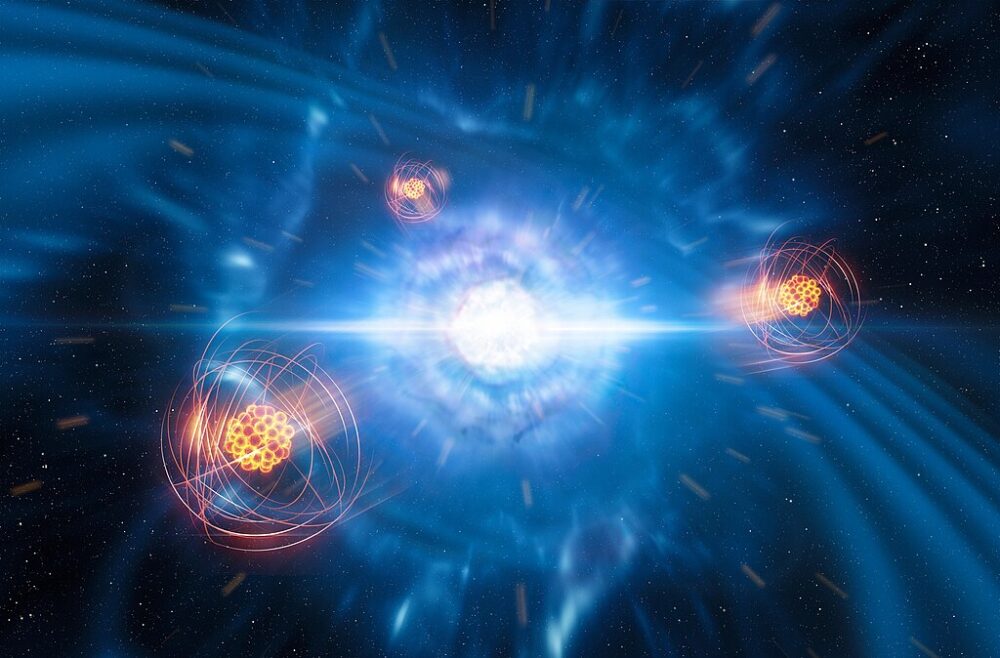

The new research proposes that objects without event horizons—like white dwarfs and neutron stars—might also lose mass through a Hawking-like process tied to gravity and curved spacetime.

If that’s true, black holes aren’t the only cosmic countdown. Dead stars and other compact remnants become part of the same slow leak into particles and radiation. That single change can dramatically shorten the maximum lifetime estimate for the universe.

4. The headline number is “shorter,” but still absurdly huge

The revised estimate often discussed is around 10^78 years for the universe’s maximum lifespan. That’s vastly shorter than earlier figures you may have seen—yet still so long it’s hard to think about.

For perspective, the universe is about 13.8 billion years old today. Even 10^78 years is effectively forever on human scales. The new idea changes the story’s shape more than it changes anyone’s daily reality.

5. This doesn’t contradict climate, stars, or anything happening now

A shorter cosmic lifespan doesn’t mean the universe is suddenly unstable. It’s still governed by the same day-to-day physics we observe, and the timescales involved are far beyond anything that affects Earth.

Our own timeline stays the same: the Sun will change dramatically in a few billion years, long before any “final” universe-wide decay matters. This research is about the ultimate limit, not an approaching deadline.

6. Why compact objects matter so much in the far future

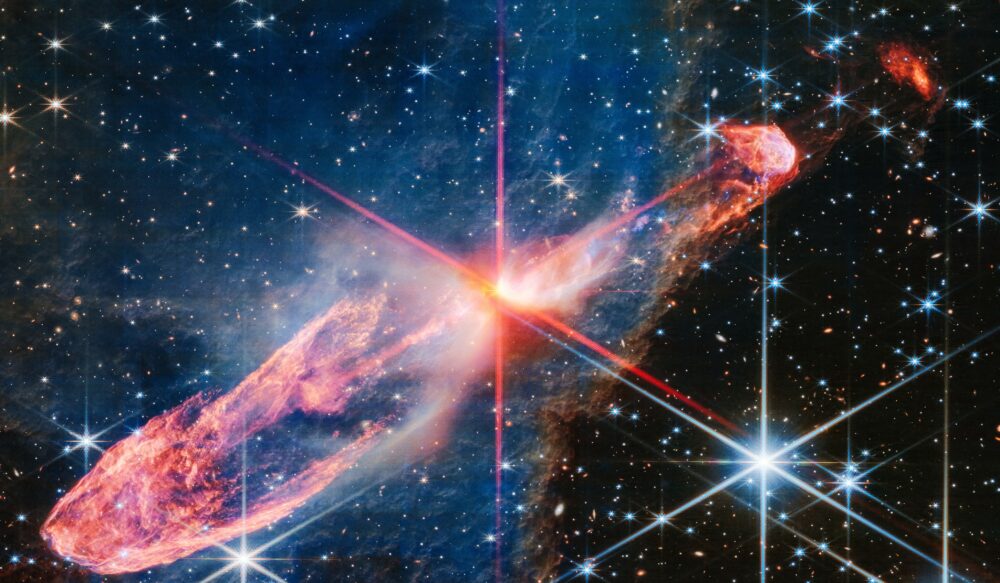

In the distant future, most ordinary stars will burn out. What’s left are long-lived remnants: white dwarfs, neutron stars, and black holes, plus scattered planets and cold debris.

If those remnants truly last essentially forever, the universe keeps “stuff” for unimaginable lengths of time. If they slowly evaporate, the universe empties out faster. So the fate of these leftovers is what sets the pace of the final chapter.

7. The idea leans on quantum physics in curved spacetime

Hawking radiation is a quantum effect tied to intense gravity. The new proposal extends that logic, suggesting curved spacetime can produce particles in ways that gradually drain mass from very dense objects.

This is hard-to-test physics, because it plays out over ridiculous timescales. But it’s still valuable: theorists use it to check whether our best models of gravity and quantum mechanics can coexist without hidden contradictions.

8. Earlier “end” estimates weren’t wrong—just based on a narrower view

Older timelines largely treated black holes as the main objects that evaporate, while other remnants were expected to persist or decay through different, uncertain mechanisms.

The new work essentially says, “Wait—what if the same basic effect applies more broadly?” That’s why the numbers can change so much without anyone claiming the previous picture was foolish. It’s a shift in assumptions, not a gotcha.

9. There’s still uncertainty, and that’s part of the point

Cosmology is full of unknowns: dark matter, dark energy, and whether protons decay at all. Any of those could alter the far-future timeline in major ways.

So this isn’t a final answer carved into stone. It’s a proposed ceiling on how long the universe can keep complex objects around, given a specific set of physics assumptions. Future theory—or data—could stretch or shrink it again.

10. The “end” most people imagine isn’t the only possible ending

Heat death is the classic ending: the universe expands, cools, and drifts toward maximum disorder. But other possibilities exist in theory, like a big crunch or a big rip, depending on how cosmic expansion behaves.

This new timeline fits the heat-death style story, where the universe slowly becomes more diffuse. It’s less about a dramatic finale and more about how long matter can resist becoming thin, cold radiation.

11. What this changes is our mental picture of the last era

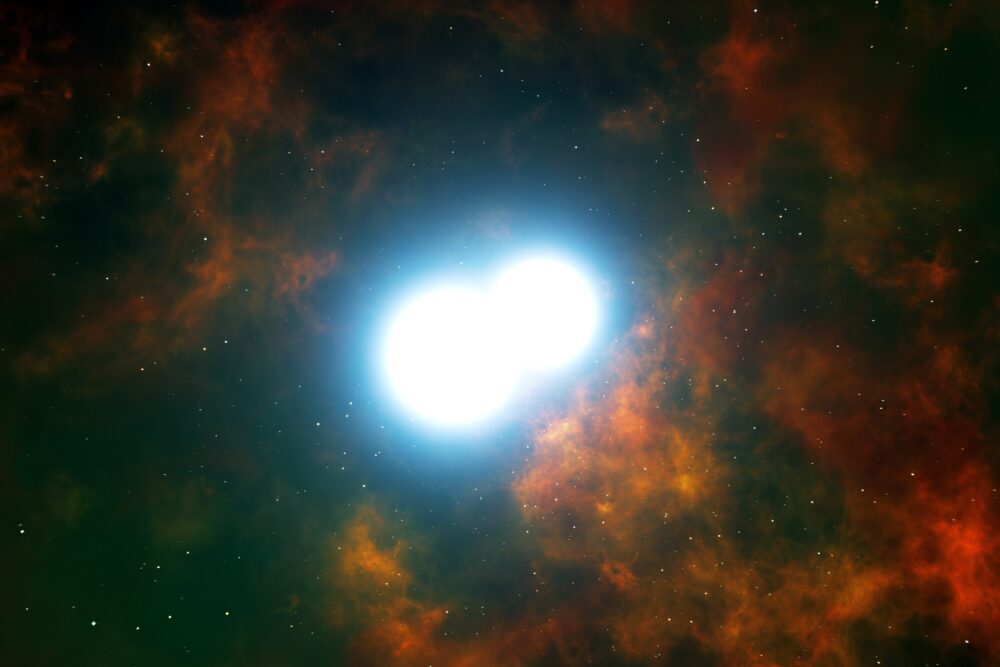

If white dwarfs and neutron stars can evaporate, the final universe isn’t a museum of silent stellar corpses. It’s a place where even the toughest leftovers gradually dissolve.

That’s a subtle but powerful change: the universe becomes more temporary than we assumed, even at the farthest edges of time. It also makes the “Black Hole Era” feel less like the whole ending and more like a phase.

12. The real takeaway: the universe may be more fragile than it looks

We’re used to thinking of matter as permanent and space as empty. These ideas suggest the opposite: even “solid” objects may have a slow expiration date written into physics.

It’s oddly comforting, too. Whether the universe lasts 10^78 years or far longer, the story is the same: change never stops. The cosmos is dynamic all the way to the end—just at a pace only math can truly hold.