Hidden medieval graffiti in Jerusalem’s Cenacle reveals who traveled far to reach a revered holy site.

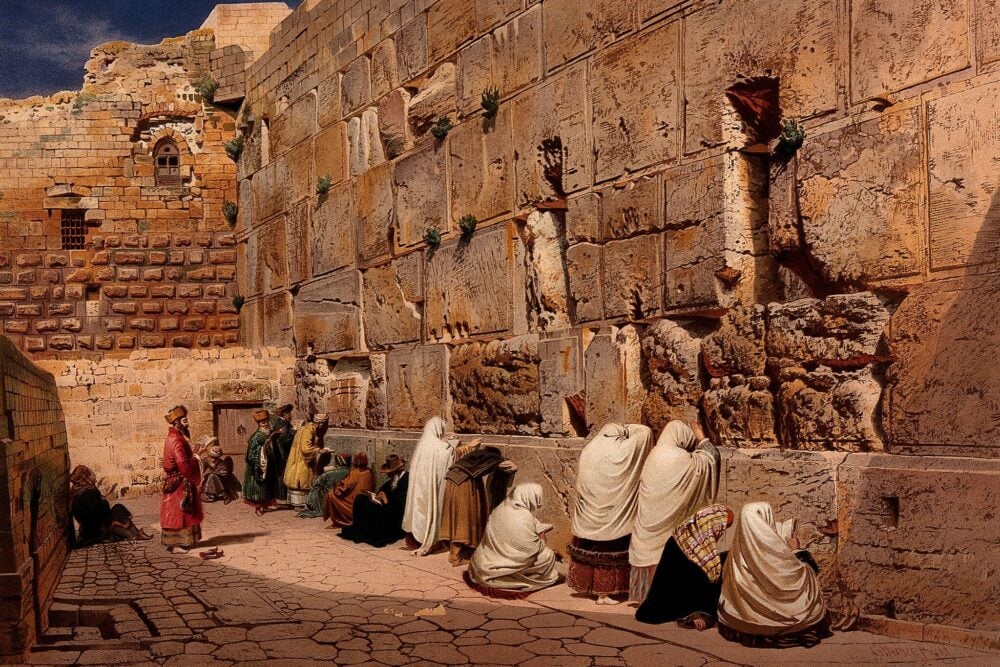

For centuries, pilgrims have visited a stone hall on Mount Zion in Jerusalem long believed by many to be the place of Jesus’ Last Supper. The room appears quiet today, but its walls have been quietly recording human presence for generations.

Using advanced imaging techniques, researchers recently uncovered dozens of hidden inscriptions, symbols, and drawings etched into the stone. Left by medieval visitors, these marks transform the room into a rare record of pilgrimage, devotion, and movement across the ancient world.

While the discoveries don’t prove this was the actual Upper Room, they reveal who believed it mattered, and how far people traveled to be there.

1. A famous place, but never a settled location

The Gospels describe a “large upper room,” but they never give an address. Over time, tradition linked the Last Supper to Mount Zion, and the hall known as the Cenacle became a destination for pilgrims seeking proximity to a sacred moment.

That distinction matters. The new discoveries illuminate how the building functioned in the medieval period, not as proof of biblical geography, but as evidence of belief, movement, and memory layered onto a specific place.

2. The markings were always there, just hard to see

For centuries, visitors scratched names, symbols, and images into the stone walls. Later renovations, plastering, and wear softened or obscured many of these marks.

Modern imaging techniques made it possible to reveal them without touching the surface. By enhancing tiny shadows and surface variations, researchers brought faint lines back into view, turning what once looked like blank stone into a densely layered historical record.

3. Graffiti was treated as serious historical evidence

Researchers didn’t approach the markings casually. Each inscription and drawing was carefully documented, traced, and analyzed using established archaeological methods.

Letter forms, symbols, and placement were compared with historical records and known styles. This systematic approach allowed scholars to treat the graffiti not as vandalism, but as verifiable evidence that can be studied, debated, and reassessed over time.

4. Coats of arms linked marks to real people

Among the most striking discoveries were heraldic shields carved into the walls. These symbols matched known noble families, allowing researchers to connect graffiti to specific pilgrimages recorded in historical documents.

In some cases, a carved emblem could be tied to a known journey, turning an anonymous mark into a personal historical footprint. The walls effectively preserve names and stories that written records alone might never have captured.

5. A written name echoed a known travel account

One inscription appears to reference a medieval pilgrim known for documenting his travels through the Holy Land. Finding his name on the wall links a written account to a physical presence in the same space.

Even when fragments are incomplete, such connections humanize history. They remind us that these were real people who wanted their journeys remembered, even if only through a small mark on stone.

6. A single date opened a larger historical debate

Among the inscriptions is a reference to “Christmas 1300,” written in a style associated with Armenian elites. That date intersects with historical debates about whether Armenian forces reached Jerusalem at the time.

Researchers stress caution. The inscription supports a possibility rather than settling the question. Still, it shows how a single etched date can connect a sacred site to wider political and historical movements.

7. A rare trace of a woman pilgrim emerged

One Arabic inscription includes grammatical clues suggesting it was written by a woman, likely a Christian pilgrim from Aleppo. Such evidence is rare in the archaeological record.

This fragment hints at stories often missing from written history. Women traveled, worshiped, and left their marks too, even if those traces are harder to recognize and preserve.

8. The walls reflect a surprisingly global crowd

The inscriptions point to visitors from many regions, including parts of Europe, the Middle East, and beyond. Arabic-speaking Christians appear to have left the largest number of marks.

This diversity challenges the idea that medieval pilgrimage was dominated by a single culture. The Cenacle functioned as a crossroads where different languages, traditions, and communities intersected.

9. Drawings reveal what pilgrims wanted to remember

Not all marks were written. Researchers documented carved images, including religious symbols, animals, and everyday figures. Visual marks may have allowed people to express devotion without sharing a language.

Some drawings appear linked to the meaning of the site itself, while others reflect broader cultural influences. Together, they show how pilgrims used images to claim presence and meaning.

10. Centuries of change explain why the messages disappeared

During the Middle Ages, the Cenacle was part of a religious complex. Later changes in control and function altered how the space was used and maintained.

Renovations and surface treatments gradually hid many inscriptions. Modern imaging doesn’t just reveal graffiti—it reveals how holy places are continuously reshaped by history, use, and reinterpretation.

11. What the discovery changes—and what it doesn’t

The newly uncovered inscriptions don’t prove where the Last Supper occurred. Archaeology has limits, especially when original texts lack precise locations.

What the discovery does change is our understanding of the site as a human space. The Cenacle’s walls act as a guestbook of medieval devotion, preserving the voices of pilgrims who believed the place mattered enough to leave a mark that endured for centuries.