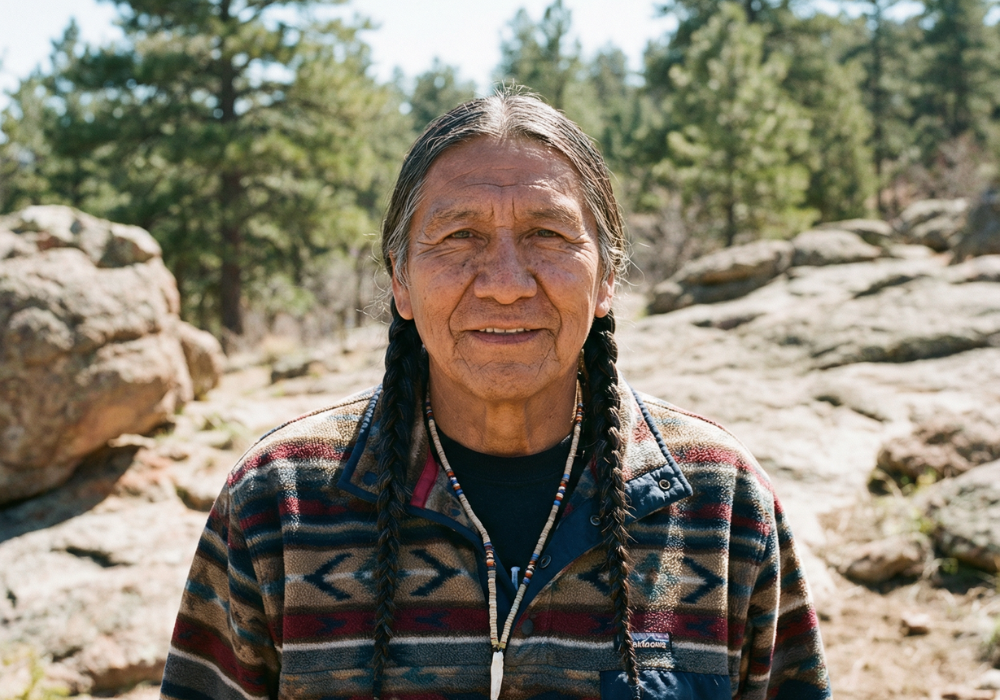

Why geography, history, and underfunded infrastructure leave tribal communities especially vulnerable.

Washington’s recent floods weren’t just “bad weather.” They were powered by atmospheric rivers, long plumes of water vapor that can dump huge amounts of rain in a single week when they stall over the Olympics and Cascades.

Tribal lands are often located along rivers, estuaries, and low-lying coastlines, so when waters rise, the damage can hit homes, roads, and cultural sites first, and evacuations can be harder to coordinate.

Climate change adds fuel: warmer air holds more moisture, making the strongest rain events heavier. That means the same kind of storm can now deliver more water, more often.

1. When the river is your neighbor, floods stop being “rare”

Many tribal communities are built near water for food, travel, and culture. That geography is a strength in normal times, but it becomes a vulnerability when rivers rise fast.

During the December 2025 floods, multiple Washington tribes declared emergencies as flood warnings persisted. When the only road in or out is threatened, “high water” quickly turns into a safety and supply-chain problem.

2. Atmospheric rivers are the Northwest’s biggest rainmakers

Think of an atmospheric river as a moving firehose in the sky. It is not a single thunderstorm. It is a long corridor of moisture that can keep feeding rain into the same watersheds for days.

When that moisture hits mountains, it is squeezed out as heavy rain. Rivers react fast, and the longer the system stalls, the higher flood risks climb across western Washington.

3. Warmer winters raise the flood risk in a sneaky way

In mountain regions, temperature is everything. If it is cold enough, storms build snowpack. If it is warmer, that same storm becomes rain, which runs downhill immediately.

As winters warm, more precipitation falls as rain instead of snow. That shortens the time between rainfall and flooding, especially for communities located downstream.

4. Rain-on-snow can turn a bad storm into a monster

One of the most dangerous setups is rain falling on existing snow. The rain adds water, and the warmer air can melt snow too, sending a double pulse into rivers.

When this happens, runoff can spike quickly. Roads wash out, culverts overflow, and erosion accelerates in places where homes and utilities sit close to riverbanks.

5. Why tribal lands often take the first hit, physically

Many reservations and tribal trust lands sit in floodplains and low-lying coastal zones for historical reasons, not because communities chose risk. Over generations, tribes were pushed onto smaller areas with limited safe high ground.

When major floods arrive, impacts stack up fast. Housing damage, infrastructure failures, and threats to culturally important places can happen at the same time. Climate pressure amplifies land-use decisions rooted in history.

6. Climate change can supercharge the storm you already recognize

Climate change does not create an atmospheric river, but it can intensify it. Warmer air holds more water vapor, and warmer oceans help feed moisture into storms before they make landfall.

During recent floods, some parts of western Washington saw close to ten inches of rain in about a week. That volume pushes rivers higher, triggers landslides, and leaves little recovery time.

More water in the sky means higher flood peaks and less absorption by already saturated ground. For communities already vulnerable, each storm becomes harder to manage than the last, especially when storms arrive closer together than they used to.

7. The infrastructure gap becomes obvious during floods

Floods do not only damage homes. They stress bridges, water systems, wastewater, power lines, and the roads emergency crews rely on.

When rivers rise, even small failures can isolate communities. Repairs take time, and recovery can lag when funding, equipment, and labor are stretched thin after widespread disasters.

8. Erosion is a slow disaster that floods speed up

Even after waters recede, the land keeps changing. Fast-moving water chews away riverbanks and coastlines, undermining roads and structures.

Some tribal communities have faced erosion pressure for years. Major floods can accelerate that process dramatically, stripping away natural buffers in a matter of days.

9. Landslides are part of the same climate story

Heavy rain does not stop at flooding. Saturated hillsides can collapse, blocking roads and damaging water lines.

As intense rain events become more common, landslide risk rises too. For communities already dealing with floods, this adds another layer of danger and isolation.

10. When homes flood, culture floods too

Flooding affects more than property. It can damage fishing access points, shellfish areas, community buildings, and sites tied to history and identity.

Displacement disrupts daily life and cultural continuity. Recovery is not just about rebuilding structures, but restoring connections to land and tradition.

11. Emergency declarations show how wide the impact really is

Emergency declarations unlock resources, but they also reveal how extensive the damage is. Tribal governments were included because their impacts were central, not secondary.

These declarations highlight the need for coordinated responses. Floods do not respect jurisdictional boundaries, and planning must include tribal nations as full partners.

12. What climate resilience looks like on tribal lands

Resilience is built through many steps: elevating buildings, reinforcing riverbanks, restoring wetlands, upgrading culverts, and improving evacuation planning.

As storms grow stronger, preparation matters more. Investing early in resilience can reduce repeated damage and help communities withstand the next flood rather than starting over each time.