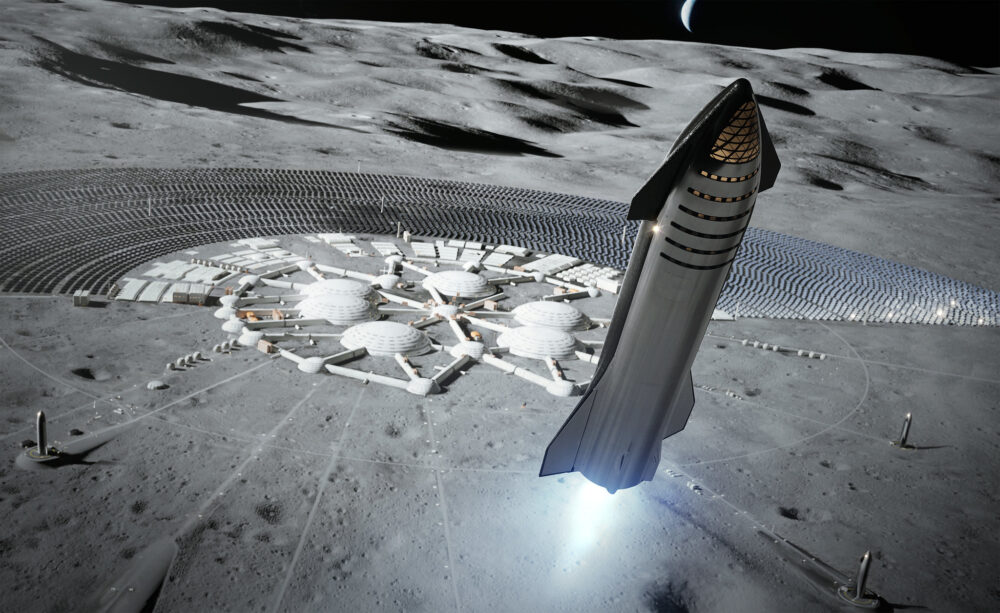

How lunar ice and resources could be used to refuel spacecraft on deep-space missions.

Calling the Moon a “gas station” sounds like sci-fi, but the idea is surprisingly practical: if you can make fuel in space, you don’t have to haul every pound up from Earth, again and again.

Scientists focus on the lunar poles because permanently shadowed craters can trap water ice. Dig it up, heat it, capture the water, and split it into hydrogen and oxygen, and you’ve got the same propellants many rockets rely on.

NASA and its partners are already testing drilling and ice-hunting tech on the Moon, because a dependable refueling stop could make lunar missions—and eventually deeper ones—cheaper, safer, and more frequent.

1. The Real Reason Everyone Wants a “Pit Stop” in Space

The “cosmic pit stop” idea starts with a simple math problem: launching mass from Earth is brutally expensive and energy-intensive. Every extra pound of propellant you carry to space forces you to carry even more propellant just to lift that propellant.

If you can refuel after leaving Earth, missions can launch lighter, reuse vehicles more often, and still reach farther destinations. It also lets planners trade “extra fuel” for more cargo, more shielding, or a bigger safety margin when something goes wrong.

2. The Moon’s South Pole Is Where the Fuel Story Begins

The Moon’s south pole is the star of this plan because some craters never see sunlight. Those permanently shadowed regions stay cold enough to preserve water ice for extremely long periods—like nature’s deep freezer.

Water is the jackpot resource. It supports drinking water and breathable air, and it can be turned into rocket propellant. That’s why missions obsess over the boring details: where the ice sits, how pure it is, and whether it’s reachable without chewing up the machinery on day one.

3. Finding Ice Is Harder Than It Sounds

Step one is finding ice in the real world, not just in models. Missions use instruments that detect hydrogen signatures, analyze surface chemistry, and watch how volatiles behave around shadowed terrain.

The goal isn’t a single “ice block.” It’s learning concentration, depth, and whether the ice is mixed like frost in dusty regolith. Those details decide whether mining is a quick scoop, a slow bake, or a nightmare of clogged drills and dusty, dirty water that’s hard to filter. That’s where most plans succeed or fail.

4. Mining on the Moon Isn’t “Digging,” It’s Survival Engineering

Mining on the Moon won’t look like a bulldozer on Earth. In a vacuum, with abrasive dust, low gravity, and extreme cold, digging systems must be sealed, rugged, and mostly autonomous to survive.

NASA and partners have been testing key pieces like lunar drilling and volatile analysis on real lunar landers. The point is to prove hardware can land, bite into the soil, and measure what comes out—because an ice map is nice, but a working drill is what turns ice into fuel.

5. Turning Ice Into Rocket Fuel Takes More Steps Than People Expect

Once you have icy material, you need to turn it into something useful. A common approach is to heat regolith to release water vapor, capture it, then purify it into liquid water you can process.

From there, electrolysis splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. Oxygen is usually the bigger “tank problem,” because rockets burn a lot of it. And storing either product as cryogenic liquid on the Moon adds insulation, power, and boil-off headaches engineers have to tame before it’s reliable.

6. The Unsexy Problem That Makes or Breaks the “Gas Station”

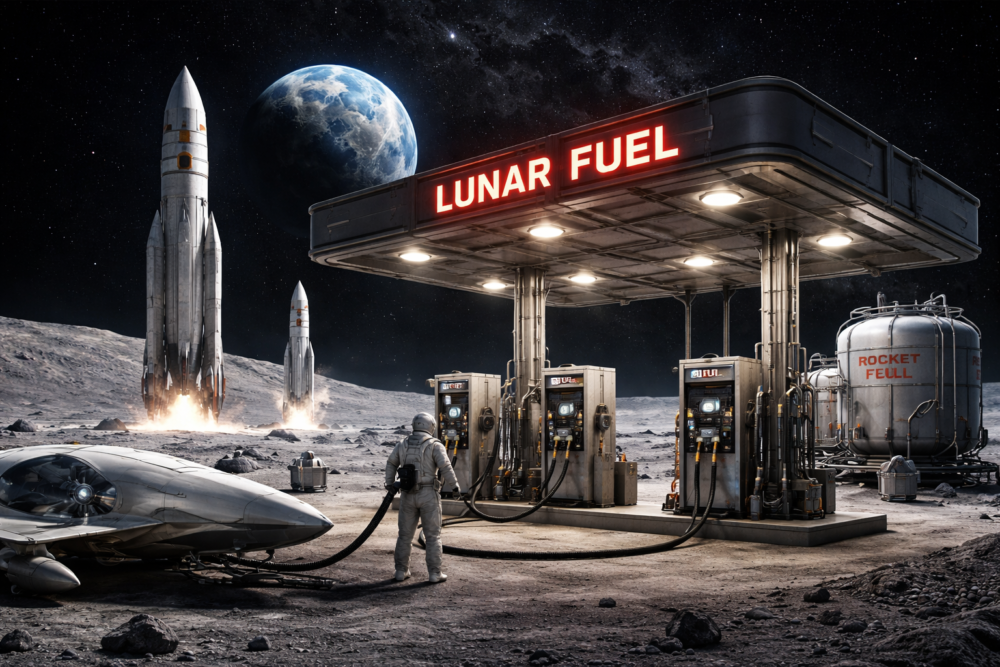

A “Moon gas station” also depends on storage—because making propellant is only half the job. You have to keep oxygen and hydrogen cold, stable, and ready for months, not hours.

That’s why researchers talk about depots: insulated tanks on the surface or in lunar orbit, plus valves and plumbing to transfer cryogenic propellants without wasting them to boil-off. Even tiny leaks or warm spots can quietly drain a whole season’s production.

It sounds fussy because it is. But storage, chill-down, and clean transfers are what turn a cool experiment into a refueling stop other missions can actually plan around.

7. You Might Not Even Need Ice First to Start “Refueling”

Water ice isn’t the only lunar fuel ingredient. The Moon’s soil is rich in oxygen bound up in minerals, and several proposed processes can extract that oxygen for rocket oxidizer.

That matters because oxidizer is the bulk of many propellant mixes. If you can make oxygen locally—even before water mining is perfect—you can reduce how much mass you launch from Earth. In early phases, local oxygen plus imported fuel could still be a major win for early missions. Oxygen is heavy, so the savings add up.

8. Who’s Actually Going to Use Lunar Fuel?

So who would buy “Moon fuel”? Think landers hopping between sites, tugs moving cargo in lunar orbit, or crews who want a serious emergency reserve before heading home, tired and low on options.

Refueling also changes mission design. Instead of one giant rocket doing everything, you can stage: launch pieces, assemble in orbit, top off, and go. That flexibility is why agencies and startups keep circling back to the pit-stop idea—it makes space travel feel less like a one-shot stunt.

9. Power Is the Hidden Boss Battle

The hardest part may be power. Mining, heating, electrolysis, and cryogenic storage all demand steady electricity, but the best ice targets sit in places that are dark, cold, and hard to reach.

One solution is solar arrays on nearby ridges that get long sunlight, sending power down by cable. Another is a mix of solar, batteries, and possibly nuclear systems. Without dependable power, the “gas station” is basically a freezer with no outlet, and everything stalls fast, no matter how smart the mining plan is.

10. The Legal and “Traffic” Problems Nobody Mentions in the Headline

There’s also the question of law and logistics. Space treaties prohibit national “ownership” of the Moon, but many countries support using space resources under certain rules, and companies want clearer operating rights.

On the ground, you need landing pads, dust control, and traffic coordination so one touchdown doesn’t sandblast a neighbor’s equipment. A fuel hub only works if the surrounding infrastructure is as carefully engineered as the chemistry—because lunar dust is an equal-opportunity menace for sensors and seals. Coordination becomes a safety issue, not a nicety.

11. Why This Isn’t Just Moon Hype

Even if the full gas-station vision takes years, the near-term wins are real: better maps of lunar ice, proven drills, improved volatile sensors, and smarter ways to store cryogenic fluids.

And the Moon is a perfect rehearsal stage. If we can learn to live off local resources there—find water, make oxygen, manage power—we’ll have a repeatable playbook for tougher places. In that sense, a lunar pit stop isn’t just about fuel; it’s practice for going farther than we’ve ever sustained.