New research shows parts of the West Coast could face a destructive tsunami within minutes of a major Cascadia quake.

Scientists warn that the Cascadia Subduction Zone—an offshore fault identified by U.S. Geological Survey research as capable of producing a magnitude-9 earthquake—could generate a powerful tsunami with very little warning. Recent modeling from Oregon State University’s Hazard Assessment Team and NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory shows that some coastal towns nearest the rupture could see waves in just 10 to 20 minutes. Emergency planners say preparedness varies widely, highlighting the need to strengthen systems before the next major Cascadia event occurs.

1. The Cascadia Subduction Zone Can Trigger a Magnitude-9 Earthquake

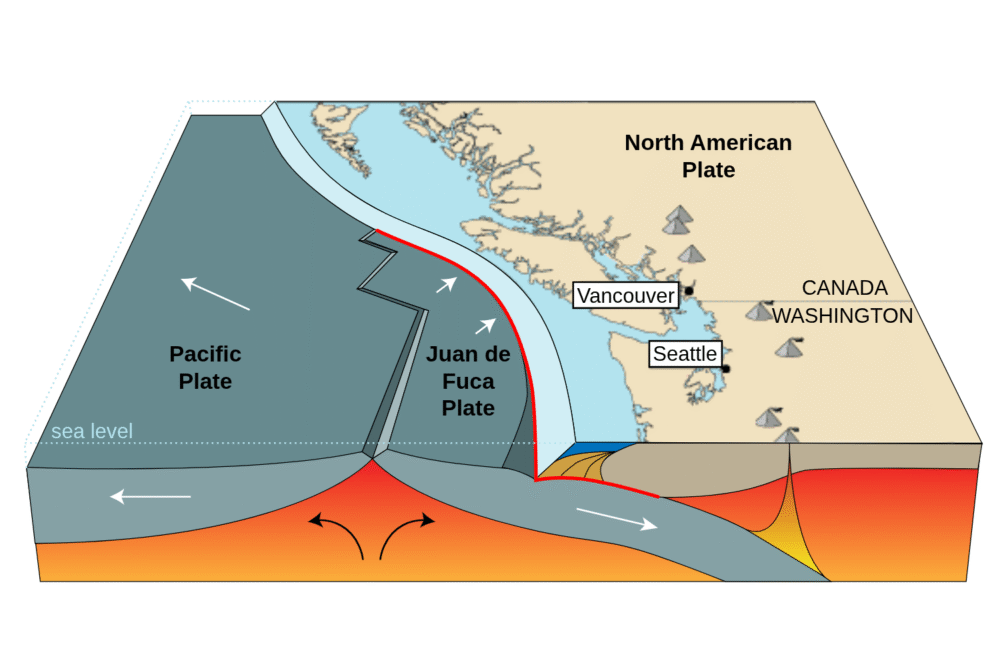

The Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) is a 600-mile-long fault where the Juan de Fuca Plate dives beneath North America. USGS research confirms that this zone is capable of producing a magnitude-9 earthquake—similar in power to the 2011 Japan disaster. Historical and geological evidence shows that the last major Cascadia quake struck in 1700, causing a tsunami that reached Japan.

Scientists say such an event will repeat in the future. Because the CSZ is offshore, the shaking would be followed almost immediately by a tsunami heading toward the Pacific Northwest.

2. Scientists Say the Next Major Cascadia Quake Is a Matter of Time

The CSZ has produced giant earthquakes roughly every 250 to 900 years, according to studies of coastal marshes, sediment layers, and submerged forests. With the last rupture occurring in the year 1700, researchers emphasize that the region is firmly within the window of possibility for another major event.

Although no one can predict the exact timing, the scientific consensus is that the probability of a powerful Cascadia earthquake in the coming decades is significant. This uncertainty keeps emergency planners focused on long-term readiness rather than prediction.

3. Tsunami Modeling Shows Some Towns Could Be Hit Within 10–20 Minutes

Studies from Oregon State University, NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory, and the Washington Geological Survey show that communities closest to the outer coast—such as Seaside, Westport, Ocean Shores, and parts of northern California—may have as little as 10 to 20 minutes after shaking before the first tsunami waves arrive.

This short window makes evacuation extremely challenging. Many residents would need to reach high ground on foot, because bridges, roads, and utilities may be damaged or unusable. The limited time underscores the importance of knowing evacuation routes ahead of any event.

4. Coastal High-Risk Zones Include Oregon, Washington, and Northern California

Hazard maps produced by FEMA, USGS, and state emergency agencies show that low-lying coastal zones in Oregon, Washington, and northern California face the most immediate danger. These include beaches, river mouths, harbors, and flat coastal plains where tsunami waves can travel far inland.

Some communities are already working to relocate schools, hospitals, and essential services to higher ground. Others remain in vulnerable locations with limited natural elevation, making long-term planning critical for safety.

5. Many Coastal Bridges and Roads May Fail After a Major Quake

Transportation studies from Oregon and Washington departments of transportation indicate that many coastal bridges, causeways, and highways are not built to withstand a magnitude-9 earthquake. Even structures that survive may shift or collapse enough to block evacuation routes.

Because the tsunami would arrive so quickly, residents cannot rely on cars for escape. Emergency planners emphasize that on-foot evacuation is the safest and most reliable method—another reason communities practice regular walking drills.

6. Vertical Evacuation Towers Could Save Lives in Flat or Low-Lying Areas

In places with little natural high ground, engineers recommend vertical evacuation structures—reinforced buildings or towers designed to withstand powerful waves. The first U.S. example, the Ocosta Elementary School tower in Washington, opened in 2016. Several more are planned along the Pacific Northwest coast.

These structures can provide refuge for hundreds of people during a fast-arriving tsunami. However, experts warn that far more towers are needed to protect the tens of thousands of coastal residents living in high-risk zones.

7. The 2011 Japan Tsunami Serves as a Model for What Cascadia Could Face

The Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan caused massive damage despite advanced warning systems. Cascadia’s geological similarity to Japan’s subduction zone makes the 2011 event an important comparison. Studies of Japan’s disaster provide insight into how infrastructure, early-warning systems, and public education affect survival rates.

Researchers note that Japan’s tsunami waves reached over 100 feet in some locations. While Cascadia’s impacts would vary widely by geography, the lessons learned from Japan are crucial for improving U.S. preparedness.

8. Emergency Planners Say Public Readiness Remains Uneven

State and federal assessments show that some communities have strong preparedness programs, evacuation maps, and regular drills—particularly in Washington and Oregon. Others have limited resources, outdated infrastructure, or populations with low awareness of tsunami risks.

This uneven readiness poses a challenge for regional safety. Planners stress that survival depends heavily on knowing evacuation routes, recognizing natural warning signs, and practicing immediate response behaviors.

9. A Cascadia Tsunami Could Sever Infrastructure for Weeks or Months

Reports from FEMA and the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission indicate that hospitals, water systems, power grids, and communication networks along the coast could suffer extensive damage. Landslides may isolate communities for days or even weeks.

Some regions may require helicopter support or boat access for rescue operations. Long-term rebuilding would be a massive undertaking, similar in scale to large international disasters.

10. Early-Warning Systems Are Improving but Still Have Gaps

NOAA operates a network of deep-ocean sensors and coastal alarms designed to detect tsunamis, and the U.S. is expanding earthquake early-warning alerts through the ShakeAlert system. However, offshore quakes close to the CSZ leave very little time between detection and wave arrival.

Scientists emphasize that natural signs—strong shaking lasting over 20 seconds, sudden sea withdrawal, or unusual ocean behavior—are still the most reliable immediate warnings for people in coastal areas.

11. Community Drills and Evacuation Planning Are Key to Saving Lives

Washington, Oregon, and California hold regular tsunami drills and “tsunami walkout” events to train residents to evacuate quickly on foot. Schools, coastal hotels, and businesses increasingly participate in preparedness activities.

Experts highlight that survival often depends on practiced routines: knowing the nearest high ground, having a backpack ready, and recognizing when to leave without waiting for official alerts. Communities that invest in drills now stand a better chance of protecting residents when the next major Cascadia event occurs.