From Asia to Europe, billion-dollar baby bonus programs have failed to reverse plunging birth rates.

Across the world, governments are spending billions to encourage citizens to have more children. From Japan’s cash grants to Italy’s “baby bonus” and China’s new family subsidies, countries facing population decline are offering unprecedented financial incentives. Yet birth rates continue to fall, and experts warn that money alone won’t solve the crisis. Rising living costs, long work hours, and shrinking social safety nets have made parenthood less appealing—proving that economic incentives can’t easily fix a cultural and structural problem.

1. Governments Are Spending Billions to Boost Birth Rates

Around the world, countries facing population decline are offering money to encourage people to have more children. From Europe to East Asia, these “baby bonus” programs include cash payments, tax credits, and childcare subsidies. Governments view falling fertility as an economic threat, with shrinking workforces and aging populations driving up costs for pensions and healthcare.

But even with billions invested, birth rates in many of these nations remain stubbornly low—often hitting new record lows each year despite generous incentives.

2. South Korea’s Fertility Crisis Shows the Limits of Money

South Korea has spent more than $200 billion on pro-natalist policies since 2006, including housing benefits and monthly payments for parents. Yet its fertility rate fell to 0.72 births per woman in 2023—the lowest in the world. Economists call it a “demographic time bomb.”

Young South Koreans say high housing costs, demanding work schedules, and expensive education make family life unaffordable. For many, cash incentives barely offset the financial and social pressures of raising children in a competitive society.

3. Japan’s Population Decline Continues Despite Decades of Incentives

Japan’s government began offering child allowances and tax breaks in the 1990s, but its fertility rate still sits around 1.3—well below the replacement level of 2.1. The country loses roughly half a million people annually as deaths far outnumber births.

Officials have described the trend as an “urgent national crisis.” Even with new programs funding fertility treatments and childcare, many Japanese couples delay or avoid parenthood entirely due to long work hours, small living spaces, and limited government childcare options.

4. Europe’s Baby Bonuses Haven’t Reversed the Trend

Many European countries introduced baby bonuses in the 2000s. Italy, Hungary, and France offer direct cash payments or tax breaks to parents, but results vary. Italy’s fertility rate is now about 1.2, and population decline is accelerating despite multiple policy revisions.

France has fared slightly better, maintaining one of Europe’s highest fertility rates at 1.8, but even that is falling. Economists say that while financial support helps, it cannot overcome cultural factors like delayed marriage and economic insecurity among younger generations.

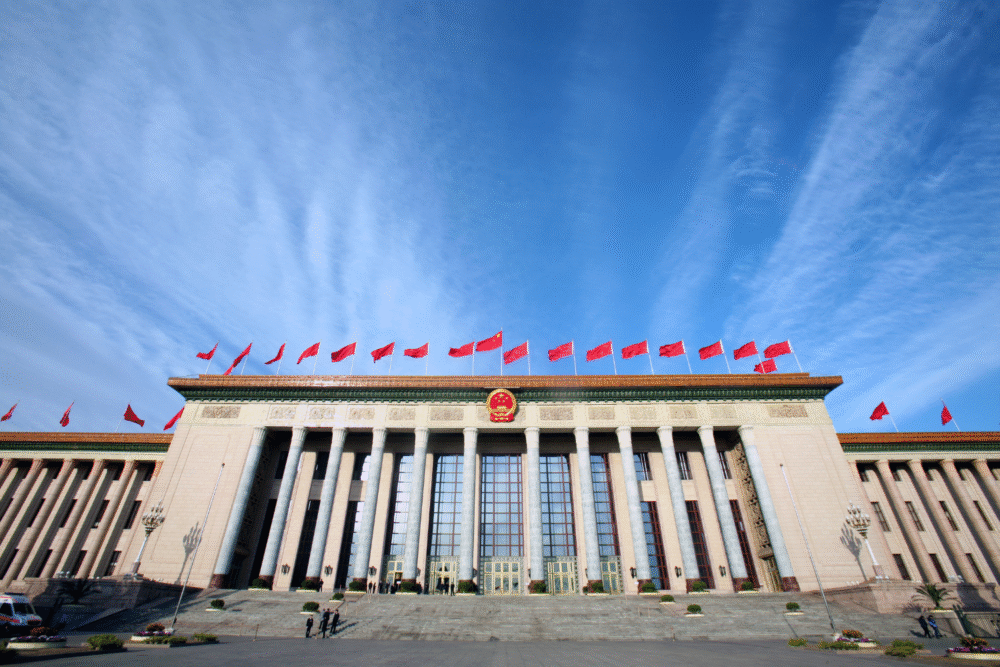

5. China’s New Baby Incentives Have Fallen Flat

After ending its one-child policy in 2016, China has tried to encourage larger families through tax deductions, housing subsidies, and paid parental leave. But the fertility rate fell to about 1.0 in 2023, the lowest in the country’s modern history.

China’s youth face high unemployment, long working hours, and rising living costs, making family life difficult to sustain. Surveys show that many young people prefer to remain single or childfree, despite state-sponsored campaigns urging them to “build the nation” through childbirth.

6. Why Financial Incentives Often Fail

Economists say cash alone rarely changes long-term fertility behavior. Studies show that while one-time bonuses may lead to temporary spikes in births, the effect quickly fades. The decision to have children depends more on job security, work-life balance, and affordable childcare than on short-term rewards.

In high-cost economies, the expense of raising a child far exceeds any government incentive. For many families, financial aid feels like a gesture rather than a real solution to structural problems.

7. The Cost of Raising a Child Keeps Climbing

In most developed countries, the cost of raising a child through age 18 now equals or exceeds the cost of a home. In the United States, that figure is estimated at more than $300,000; in Japan and South Korea, it’s similar once education expenses are included.

Younger generations often feel that parenthood means giving up financial independence. Without systemic reforms—like affordable housing, flexible work schedules, and universal childcare—cash incentives can’t offset the long-term costs families face.

8. Working Women Bear the Heaviest Burden

In many low-birth-rate countries, women cite career disruption as a major reason for not having children. Limited maternity leave, lack of childcare, and workplace discrimination make balancing family and employment extremely difficult.

Experts note that the countries with the highest fertility rates—such as Sweden and Norway—tend to have strong gender equality, paid parental leave, and state-funded childcare. That suggests cultural and workplace reforms are more effective than direct payments in supporting sustainable family growth.

9. The Psychological Factor: Parenthood No Longer Feels Necessary

In wealthy societies, social norms around marriage and children have shifted dramatically. Many young adults no longer see parenthood as an essential part of adulthood. Instead, they prioritize career, travel, and personal freedom.

Demographers say this cultural shift plays a major role in declining birth rates. In places like Japan, South Korea, and Germany, surveys show that more than 40% of young adults in their 20s and 30s don’t plan to have children at all, regardless of financial support.

10. The Economic Risks of a Shrinking Population

Fewer births mean fewer workers in the future, creating challenges for national economies. Aging populations drive up healthcare and pension costs while reducing the tax base. Economists warn that countries like Japan and Italy face shrinking labor forces and slower growth as a result.

Automation and immigration can help fill gaps, but not fast enough to offset the decline. Without a stable younger population, long-term economic stability becomes harder to maintain.

11. Alternative Solutions Are Emerging

Instead of direct payments, some countries are now testing broader family support systems. France invests heavily in subsidized childcare, Sweden offers yearlong paid parental leave for both parents, and Estonia provides free early education.

These policies appear more effective at stabilizing fertility rates than simple cash transfers. By reducing the daily burden of parenting, they make it easier for families to choose to have children—and to have more than one.

12. Why Experts Call It a Billion-Dollar Mistake

The consensus among economists and demographers is clear: paying people to have babies doesn’t solve the deeper problems behind falling birth rates. It’s an expensive strategy with limited, short-term results.

Experts argue that true demographic recovery requires structural change—affordable housing, job stability, gender equality, and cultural shifts that make family life compatible with modern aspirations. Until those issues are addressed, billion-dollar incentives will keep producing the same disappointing outcome: fewer babies, higher costs, and mounting frustration for policymakers.