New research suggests the French emperor’s greatest defeat may have been caused by a microscopic enemy.

For more than two centuries, historians have blamed brutal winter cold for destroying Napoleon’s once-mighty army as it retreated from Russia in 1812. But new scientific evidence points to a hidden culprit. Researchers analyzing the remains of French soldiers found traces of ancient bacteria in their bones—microbes capable of causing deadly trench fever and typhus. These infections may have spread rapidly through exhausted, freezing troops, turning retreat into catastrophe. The discovery offers a chilling reminder that even history’s most powerful armies can fall to enemies far smaller than themselves.

1. Napoleon’s Catastrophic Retreat From Russia

In 1812, Napoleon Bonaparte led one of the largest military forces in history into Russia — more than 600,000 soldiers. But as his troops retreated that brutal winter, disaster struck. Freezing temperatures, starvation, and exhaustion turned the once-glorious campaign into one of history’s deadliest military collapses.

By the time survivors limped back toward France, only a fraction remained alive. For generations, historians blamed Russia’s punishing cold for the devastation. Now, new research suggests there may have been another, invisible killer stalking the army from within.

2. A New Clue Buried in the Frozen Soil

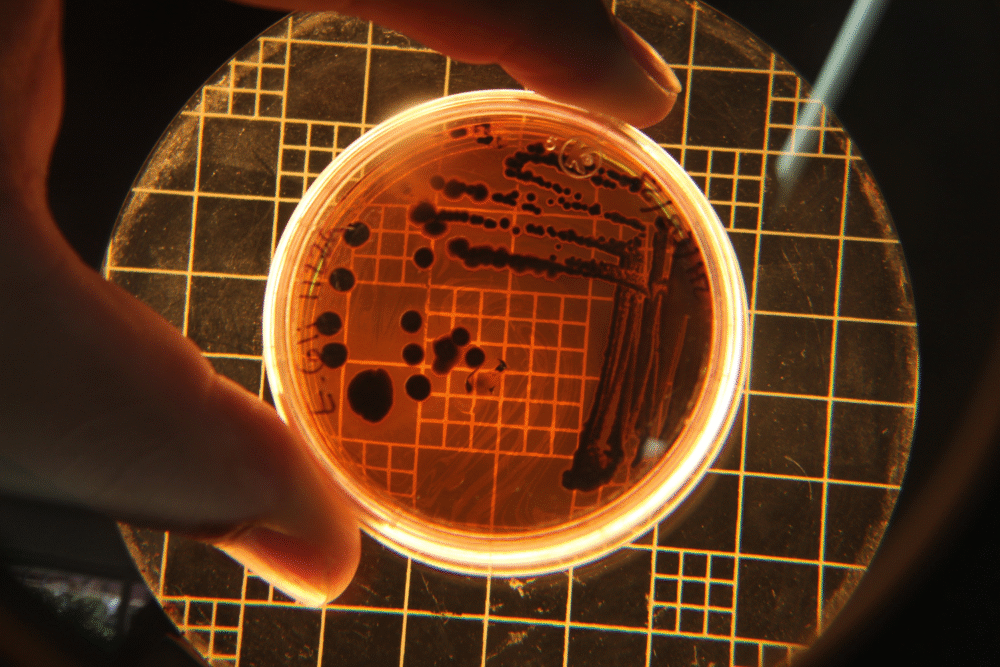

Centuries after the retreat, archaeologists unearthed a mass grave near Vilnius, Lithuania — one of the final waypoints on Napoleon’s doomed march home. Inside lay the skeletal remains of dozens of soldiers who never made it back.

The team noticed unusual preservation of bone and dental material, allowing scientists to extract tiny fragments of DNA. They hoped to uncover not just who these men were, but how they died. What they found hidden in their bones stunned historians and microbiologists alike.

3. Ancient DNA Reveals a Microscopic Enemy

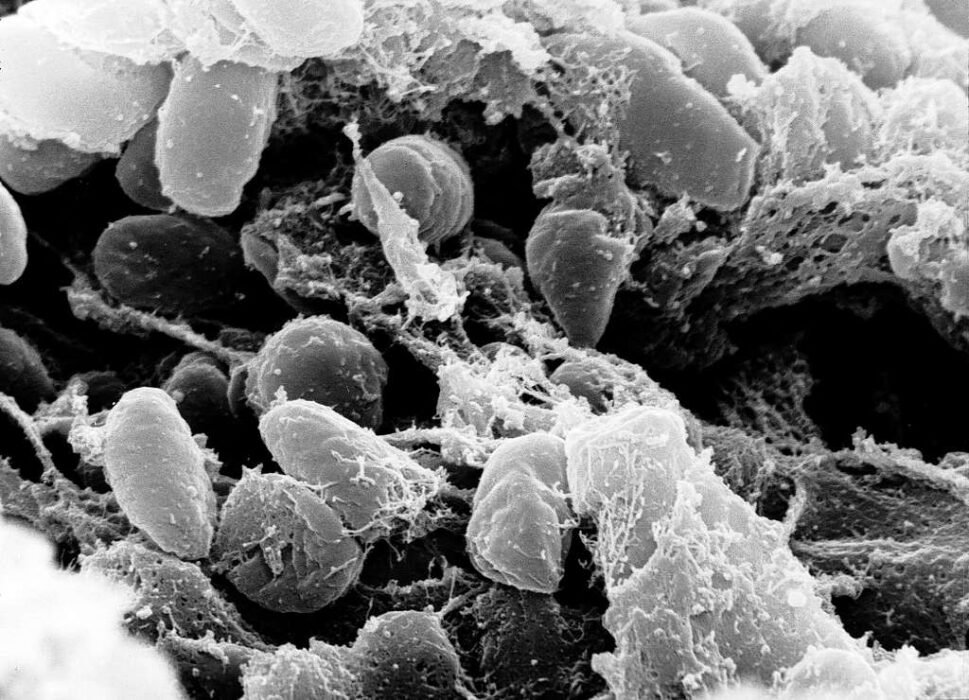

Using advanced sequencing tools, researchers identified DNA from two notorious bacteria — Bartonella quintana and Rickettsia prowazekii. These pathogens are responsible for trench fever and epidemic typhus, diseases spread by body lice.

In the filth and cold of Napoleon’s retreat, soldiers had little chance to wash or change clothes. Lice thrived in the folds of their uniforms, silently infecting troops as they marched. Scientists believe these diseases may have spread rapidly through the exhausted army, compounding the effects of hunger and frostbite.

4. How Lice Became Napoleon’s Deadliest Foe

Lice were a constant companion of soldiers in the 19th century, but few realized the insects carried lethal microbes. Once infected, victims suffered high fevers, delirium, rashes, and heart strain — symptoms nearly impossible to treat in the field.

As Napoleon’s forces fled the Russian front, medical supplies ran out and camp hygiene collapsed. With temperatures plummeting below –30°C, lice-infested uniforms became breeding grounds for disease. The microbes likely swept through the army faster than any enemy cavalry charge could.

5. The Symptoms That Mimicked Hypothermia

Historical records describe soldiers collapsing in the snow, shivering uncontrollably, and slipping into unconsciousness — signs once thought to be hypothermia. But researchers now realize many of these may have been bacterial infections taking hold.

Typhus and trench fever both cause extreme fatigue, confusion, and circulatory failure. In a frozen landscape, their victims would have appeared simply “frozen to death.” This overlap may explain why the true cause remained hidden for centuries, buried beneath layers of myth and frost.

6. How Science Solved a 200-Year-Old Mystery

It took modern genetics to confirm what eyewitnesses could not. By isolating bacterial DNA from ancient bone samples, scientists proved these infections existed among Napoleon’s troops at the time of their retreat.

This marks one of the earliest uses of microbial forensics to rewrite a major historical event. The finding not only reshapes how historians view Napoleon’s defeat but also reveals how disease, not just weather or warfare, has repeatedly changed the course of history.

7. A Pattern Repeated Throughout History

Napoleon’s army wasn’t the first — or last — to fall to invisible enemies. Disease has crippled countless campaigns, from malaria during Alexander the Great’s conquests to dysentery in World War I trenches.

In each case, microscopic killers exploited the same weaknesses: exhaustion, hunger, and poor sanitation. The 1812 outbreak adds another chapter to that long story, showing how even the most disciplined army can crumble when biology turns against it.

8. The Human Toll Behind the Numbers

More than 400,000 soldiers perished during the retreat from Russia. Some froze, others starved — but now it’s clear many suffered long, agonizing deaths from infection. Letters from surviving officers describe entire units collapsing “without battle or shot fired.”

For the soldiers, there was no understanding of the enemy within. Medical knowledge at the time couldn’t identify microbes, let alone treat them. Their suffering, once blamed solely on the Russian winter, now carries a tragic new layer of meaning.

9. Lessons for Modern Science and Medicine

The study of Napoleon’s soldiers offers a powerful reminder that disease surveillance remains as vital as ever. Even in modern armies and disaster zones, infections can spread rapidly when hygiene breaks down.

By applying genetic tools to ancient remains, researchers are learning how past outbreaks behaved — knowledge that could improve how we prepare for future epidemics. History, it turns out, can still teach lifesaving lessons from the bones of the fallen.

10. Rewriting the Legend of Napoleon’s Fall

For over two centuries, the image of Napoleon’s frozen army symbolized the limits of ambition and the cruelty of nature. But this new discovery reframes that narrative: the emperor’s downfall wasn’t just due to snow and ice, but to biology’s smallest assassins.

The microbes that ravaged his soldiers remind us how fragile even the greatest empires can be. In the end, Napoleon’s most relentless enemies weren’t Russian generals or bitter cold — they were microscopic foes no one could see coming.