As satellites and rocket parts fall from orbit with growing frequency, experts warn that global laws are decades behind the danger.

Around the world, pieces of space junk—from defunct satellites to spent rocket stages—are crashing back to Earth more often than ever. While most burn up harmlessly, some survive reentry, landing dangerously close to populated areas. Scientists and legal experts warn that as space launches multiply, the odds of serious accidents are climbing—but international regulations remain outdated and unclear. With no consistent rules on who’s responsible for falling debris, the next major “crash from space” may spark a global reckoning.

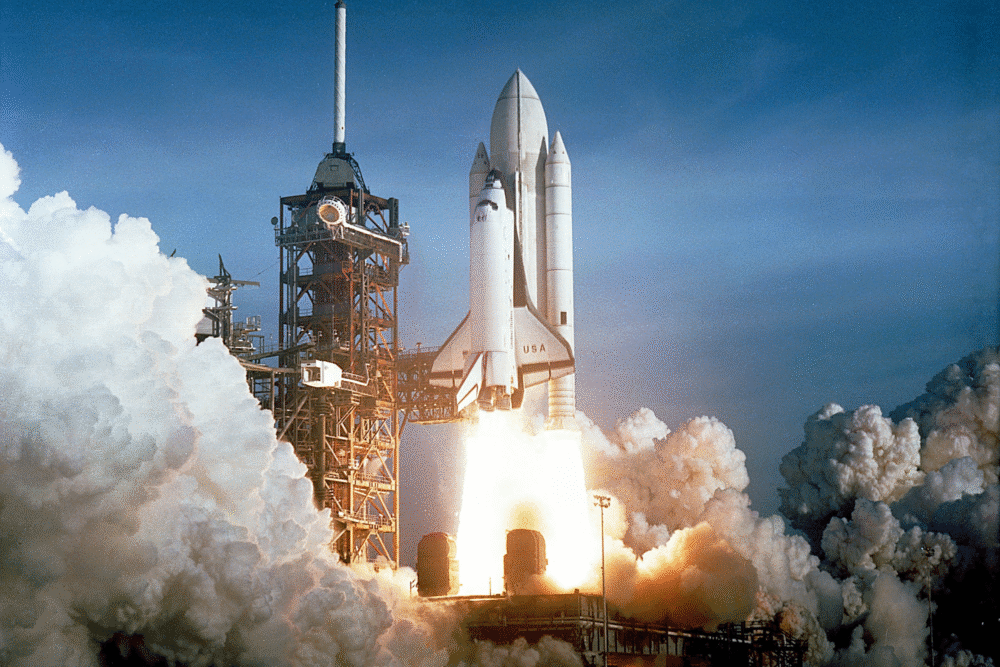

1. Space Debris Reentries Are Becoming More Frequent

The European Space Agency (ESA) estimates that about one object reenters Earth’s atmosphere every day. Most are small fragments that disintegrate on descent, but large pieces occasionally survive. The rise in launches from companies like SpaceX, Rocket Lab, and China’s Long March program has sharply increased the total number of satellites and rocket stages in orbit.

According to the U.S. Space Surveillance Network, more than 11,000 tons of human-made material currently orbit Earth. Each new mission adds to the debris risk, making reentries a routine part of modern spaceflight.

2. Rocket Parts Pose the Greatest Danger

While small satellites and fragments usually burn up, the heaviest components—such as rocket bodies—often survive reentry. Some weigh several tons and can scatter debris across wide areas. China’s Long March 5B rockets have drawn criticism for uncontrolled reentries in 2020, 2022, and 2023, when debris landed in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia.

NASA and ESA design most rockets to deorbit safely or burn completely. However, uncontrolled reentries from older or foreign systems still pose a real, if statistically small, danger to people and property on the ground.

3. The Odds of Being Hit Are Low—but Rising

A 2023 study published in Nature Astronomy found that the risk of a falling rocket part killing or injuring someone on Earth may reach 10% over the next decade if current launch rates continue. That number reflects the global cumulative probability, not the risk to an individual.

The chance of any one person being struck remains extremely small—less than one in several billion—but the growing number of launches increases cumulative exposure. Researchers say the threat is no longer negligible and deserves serious policy attention.

4. More Launches Mean More Potential Crashes

The commercial space industry is expanding rapidly. In 2024, there were more than 230 orbital launches worldwide—the highest in history, according to Spaceflight Now. SpaceX alone accounted for over half of them with its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy missions.

Each rocket launch introduces multiple components—boosters, adapters, and fragments—that can later reenter. With megaconstellations like Starlink planning tens of thousands of satellites, managing safe reentry paths has become a pressing global issue.

5. Not All Debris Burns Up on Reentry

Contrary to popular belief, not everything entering the atmosphere disintegrates completely. High-density materials such as titanium, stainless steel, and composite alloys can survive the intense heat of reentry.

Recovered debris from past incidents, including a 2022 SpaceX Crew Dragon trunk segment found in Australia, shows that fragments can remain intact after falling thousands of miles. Although no serious injuries have yet been reported, the growing frequency of such recoveries underscores how unpredictable reentry paths can be.

6. Tracking Space Junk Is a Constant Challenge

NASA and the U.S. Department of Defense monitor more than 25,000 trackable pieces of debris larger than 10 centimeters. Millions of smaller fragments remain undetectable but can still cause significant damage.

Tracking objects reentering the atmosphere is complex due to fluctuating solar activity, which changes atmospheric density and drag. Even short-term predictions about where debris will fall often carry hundreds of kilometers of uncertainty—making advance warnings difficult.

7. The Legal Framework Dates Back to the 1970s

The main international law governing space debris is the 1972 Liability Convention, part of the United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty framework. It makes nations responsible for damage caused by their space objects, even after reentry.

However, the treaty doesn’t specify standards for safe reentry, cleanup, or liability for harm to the environment. With private companies now dominating launches, the legal gap between national responsibility and corporate activity has widened, leaving unclear who pays if debris causes damage.

8. Only One Nation Has Ever Filed a Space Damage Claim

Despite thousands of reentries since the dawn of the space age, only one international claim has ever been filed under the Liability Convention. In 1978, Canada demanded compensation from the Soviet Union after a nuclear-powered satellite, Cosmos 954, scattered radioactive debris across northern Canada.

The Soviet Union paid $3 million in damages, but no other case has reached that level of accountability. Most incidents since then have been treated as accidents with no formal legal resolution.

9. Some Countries Are Creating New Guidelines

Recognizing the growing threat, agencies such as NASA, ESA, and Japan’s JAXA are developing stricter standards for “passivation” (making spent rockets inert) and planned reentries. The U.S. Federal Communications Commission now requires low-Earth orbit satellites to deorbit within five years after mission completion, down from the previous 25-year rule.

These rules aim to reduce the accumulation of long-lived debris, though compliance varies across national programs. Experts say consistent global enforcement is still lacking.

10. Scientists Are Developing Technology for Controlled Reentry

Researchers are exploring new methods to ensure safe reentry, including drag sails, propulsion-assisted deorbit burns, and even active debris-removal missions. ESA’s ClearSpace-1, launching in 2026, will be the first mission designed to capture and deorbit a defunct satellite.

These innovations could help prevent uncontrolled reentries, but they come with high costs and technical challenges. Many smaller operators lack the resources to include dedicated reentry systems on their spacecraft.

11. Communities Are Beginning to Experience the Impact

Residents in regions such as Western Australia, the Maldives, and rural China have reported finding large metallic debris from reentering rockets. While most incidents cause no injuries, they highlight how unpredictable trajectories can bring space junk down near populated areas.

In 2022, parts of a Chinese Long March rocket landed in the Philippines, prompting international criticism of uncontrolled reentries. With launch traffic increasing across Asia, Africa, and South America, more communities may face similar events.

12. The Push for Global Regulation Is Gaining Momentum

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) and several space agencies are calling for updated global rules on reentry safety and debris mitigation. The goal is to make controlled reentry or atmospheric disintegration mandatory for all large spacecraft.

As private companies launch thousands of satellites each year, experts warn that voluntary guidelines are no longer enough. Without coordinated international oversight, falling debris could become one of the defining challenges of the modern space age.