This powerful climate cycle is poised to drench some states while drying out others.

The climate pattern known as El Niño is heating up again—and forecasts suggest that 2025 could bring one of the most disruptive versions in recent memory. El Niño refers to the warming of ocean waters in the central and eastern Pacific, which shifts atmospheric patterns around the globe.

For the Western U.S., this can mean anything from intense storms and flooding to unseasonal drought and dangerous heatwaves. Scientists are already warning that the emerging signal looks strong, with the potential to scramble regional weather in ways we haven’t seen in decades.

The stakes are high for agriculture, water supply, wildfire risk, and even infrastructure resilience. Understanding what may be coming isn’t just about curiosity—it’s about preparation. These are the ripple effects that 2025’s El Niño could unleash across the West.

California could swing from drought to deluge in a matter of weeks.

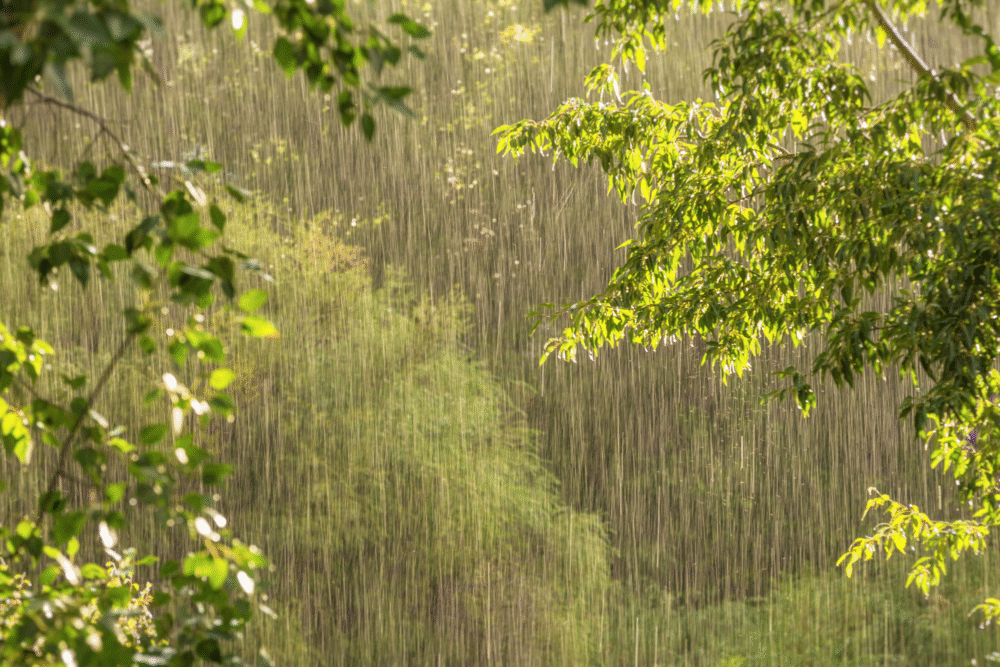

El Niño years have a history of supercharging the Pacific storm track—and for California, that often means an onslaught of moisture-laden atmospheric rivers. After years of withering drought, the state could be walloped by flooding rains, washed-out roads, and landslides.

The central and southern regions are particularly vulnerable to sudden shifts, where reservoirs might swing from dangerously low to overfilled in short order. Farmers may struggle to adapt planting schedules, and emergency services could be stretched thin.

While the precipitation is welcome, the speed and volume it arrives in can cause more harm than good. Water infrastructure and flood defenses will be put to the test. And if history repeats itself—like the winter of 1997-98—residents may need to brace for some of the most chaotic and damaging storms in decades.

The Pacific Northwest might see a warmer, drier winter than normal.

While California may be drenched, the Pacific Northwest could face the opposite problem. El Niño typically shifts the jet stream southward, diverting storms away from Washington, Oregon, and parts of Idaho. That means less snowfall in the Cascades and warmer temperatures across the board.

Ski resorts could be hit with lower turnout and patchy coverage, while water managers worry about future shortages. Without a robust snowpack, spring and summer 2026 could be dry and risky for fire season. Agriculture—from vineyards to orchards—may feel the pinch from stressed water supplies.

El Niño doesn’t guarantee these conditions, but past strong events suggest the pattern is more likely than not. For a region used to soggy winters, the change might feel unnervingly dry—and the long-term implications could ripple deep into next year.

The Southwest could get rare relief from relentless drought.

El Niño often brings wetter-than-average winters to the Desert Southwest, offering a rare reprieve from chronic dryness. States like Arizona and New Mexico could see more frequent rains, potentially replenishing parched soil, refilling depleted reservoirs, and even boosting the Colorado River’s sagging flow.

While too much rain at once poses flash flood risks, especially in canyon country, the longer-term effect might be positive. Ranchers and farmers may enjoy better grazing conditions, and native vegetation might see a resurgence. However, this relief isn’t always guaranteed. The strength and persistence of the 2025 El Niño will determine just how beneficial it turns out to be.

Still, after years of escalating drought and water restrictions, even a single season of enhanced precipitation could feel like a blessing—and buy time for struggling ecosystems and water systems.

Sierra Nevada snowpack may become dangerously unpredictable.

The Sierra Nevada is a crucial water bank for California, and El Niño can wreak havoc on its snowpack. Instead of steady snowfall, 2025 could bring torrential rain at high elevations, leading to snowmelt during the heart of winter. This disrupts water storage, impacts ski tourism, and heightens flood risks downstream.

Alternating cycles of snow, melt, and refreeze can also destabilize slopes, increasing avalanche threats. In recent strong El Niño years, some ski resorts saw rainfall ruin holiday bookings, while others struggled to predict safe backcountry conditions. For water managers, this volatility makes planning nearly impossible.

A warm, wet El Niño challenges the assumption that winter will reliably build snowpack. The Sierra’s future may look increasingly slushy, turning what was once a dependable reservoir into a seasonal wildcard with major consequences.

Flash floods and mudslides could plague fire-scarred landscapes.

After years of intense wildfires, much of the Western U.S. is dotted with burn scars—areas where vegetation no longer holds soil in place. During an El Niño year, these vulnerable zones are at heightened risk for flash floods and debris flows.

Heavy rains, especially over steep terrain, can trigger deadly mudslides in seconds. In places like California’s foothills or Colorado’s canyons, this is more than a theoretical threat—it’s a repeating nightmare. Emergency crews may be forced into rapid-response mode as storms overwhelm drainage systems. Communities still recovering from past fires might find themselves facing yet another disaster, compounding trauma and economic loss.

The collision of climate extremes—fire followed by flood—is becoming more common, and El Niño could amplify this brutal sequence. Residents in high-risk areas need early warnings and evacuation plans.

Drought-weakened trees could fall victim to intense storms.

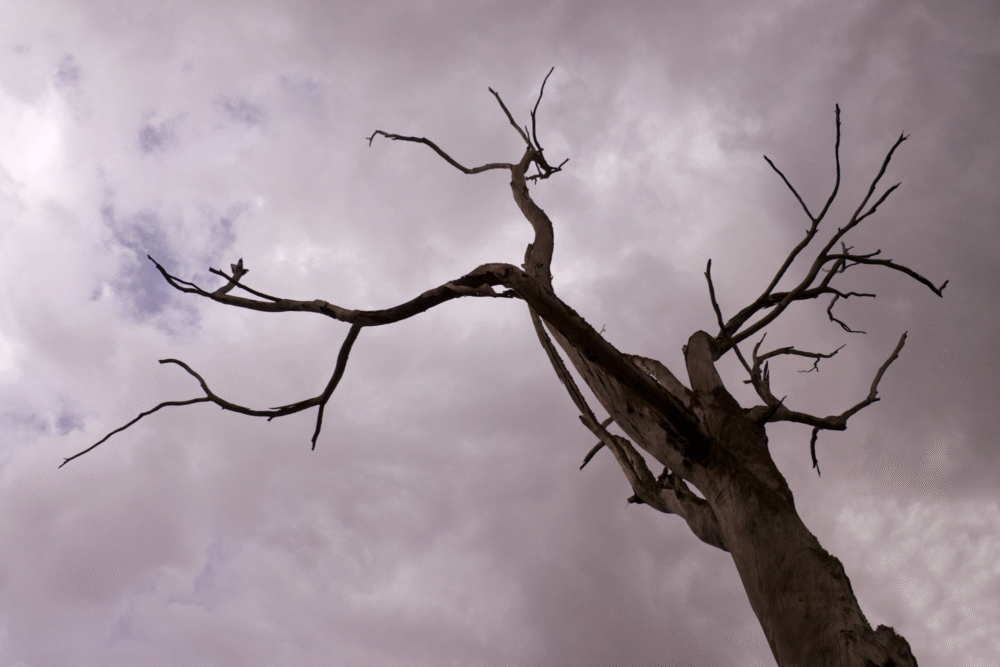

Across the West, millions of trees are already stressed by years of drought, bark beetle infestations, and wildfires. An El Niño-driven storm season could be the final blow. High winds, saturated soil, and repeated deluges can bring down weakened trees in forests and neighborhoods alike.

This not only disrupts power lines and roads but poses serious safety hazards. The cumulative effect may be especially pronounced in places like Northern California and the Sierra foothills, where forests meet human development. Fallen trees also contribute to future fire risk by creating dense fuel beds once they dry.

Urban areas with old-growth shade trees might see widespread damage. What seems like a gift of rain may leave behind costly wreckage, as overstressed trees snap under pressure. Maintenance and monitoring will be more critical than ever.

Fire risk may shift to unexpected months and regions.

El Niño doesn’t eliminate wildfire risk—it moves it. While wetter winters can reduce immediate fire conditions, a flush of new vegetation can dry out quickly in spring or summer, creating fresh fuel. Regions like Southern California or the Great Basin may face late-season flare-ups if warming follows a wet winter.

The timing becomes unpredictable, forcing fire crews to stay on alert long after traditional seasons end. In some past El Niño years, wildfires surged not in July, but in October or even November, catching communities off-guard. And in drier zones like eastern Oregon, the usual fire timeline may be flipped entirely.

This variability stretches resources thin and complicates firefighting strategies. The Western U.S. will need to rethink what “fire season” means as El Niño reshapes the calendar—and where risks crop up next.

Reservoir management will be more complex than ever.

El Niño might bring much-needed rain and snow—but for reservoir operators, this creates more problems than solutions. Timing and volume matter. Too little rain in the right months won’t help long-term storage. Too much at once may require urgent water releases to avoid overflow, which can create downstream flood risks.

Some reservoirs are still low after years of drought, while others have little buffer room left. Water agencies must make fast decisions with incomplete forecasts, gambling between conservation and flood prevention. Mistakes are costly. In states like California and Nevada, millions depend on coordinated reservoir management for drinking water, agriculture, and hydroelectric power.

El Niño raises the stakes by injecting chaos into an already stressed system. One overly warm winter storm could melt snow prematurely and unravel months of careful planning.

Western cities may need to rethink emergency planning fast.

Urban areas across the West aren’t ready for the speed and scale of El Niño-driven weather swings. Cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Salt Lake City could see overwhelmed drainage systems, closed freeways, and emergency shelters strained by storm damage. Heatwaves may follow rain events, creating health risks for unhoused populations and vulnerable residents.

Local governments often lack flexible plans that account for wild variability. El Niño’s impacts don’t arrive gradually—they crash in. City planners may need to accelerate investments in green infrastructure, climate-resilient roads, and public health responses.

With the added possibility of compounding events—floods, followed by fires, followed by heat—communities that plan now will fare far better. The old models for seasonal weather simply don’t apply anymore. El Niño is rewriting the rules, and cities can’t afford to be caught flat-footed.

The Forecast Isn’t Set—But the Stakes Are Clear

El Niño may be a naturally recurring climate pattern, but 2025’s version is shaping up to be anything but ordinary. For the Western U.S., this looming system could scramble everything from snowpack reliability and wildfire timing to urban flood control and water security.

While no forecast is perfect, the signals are too strong—and the consequences too widespread—to ignore. Whether you’re a homeowner, policymaker, farmer, or city dweller, the time to prepare is now.

Because once El Niño arrives in full force, there won’t be much room left for reacting—only responding. The smartest move? Start adapting before the first storm hits.