Scientists say Antarctica’s most dangerous glacier is hanging on by a thread—and it could snap fast.

Scientists warn that Antarctica’s most dangerous glacier—Thwaites—is hanging on by a thread, and if it gives way, the world will feel the impact. Often called the “Doomsday Glacier,” Thwaites is rapidly destabilizing due to warm ocean currents melting it from below.

According to glaciologist Ted Scambos, a senior research scientist at the University of Colorado Boulder, “Thwaites is the widest glacier in the world and it’s only weakly anchored. If it collapses, it could destabilize the rest of West Antarctica.”

That collapse alone could raise sea levels by over two feet and trigger a chain reaction of melting. Cities, coastlines, and entire ecosystems stand in the path of what could be a global flooding crisis. The clock is ticking—and faster than anyone hoped.

1. Thwaites Glacier is melting from below faster than previously thought.

Unlike surface melting seen in many glaciers, Thwaites is being eaten away from beneath. Warm ocean currents are flowing beneath the ice shelf, causing it to thin and crack. This undercutting weakens the glacier’s ability to remain anchored to the seabed, increasing the risk of large chunks breaking off.

Scientists studying the area via remote-operated submersibles and radar-mapping say melt rates have doubled in the last decade. This internal decay isn’t visible from above, making it more dangerous—melting can advance without warning. When the foundation goes, the rest of the glacier may follow.

Once it starts retreating irreversibly, we could see a rapid acceleration in ice loss, contributing to major sea level rise globally. The hidden nature of this melting is what makes Thwaites such a terrifying wild card in the climate crisis.

2. If Thwaites collapses, it could raise sea levels by over two feet.

Thwaites Glacier holds enough ice to single-handedly raise sea levels by more than two feet. That’s just its direct contribution. If its collapse destabilizes neighboring glaciers in West Antarctica, the sea level rise could triple.

Entire low-lying nations and major coastal cities—like New York, Miami, and Shanghai—would face flooding risks far beyond current projections. Unlike slow, predictable sea rise, this scenario could unfold in bursts, overwhelming infrastructure in a short span. The collapse wouldn’t just affect distant polar regions—it would immediately redraw global coastlines. Insurance markets, real estate, and shipping routes would all be impacted.

The financial cost would be astronomical, and the humanitarian toll devastating. That’s why climate experts warn Thwaites is not just an environmental concern—it’s a geopolitical time bomb with global economic consequences.

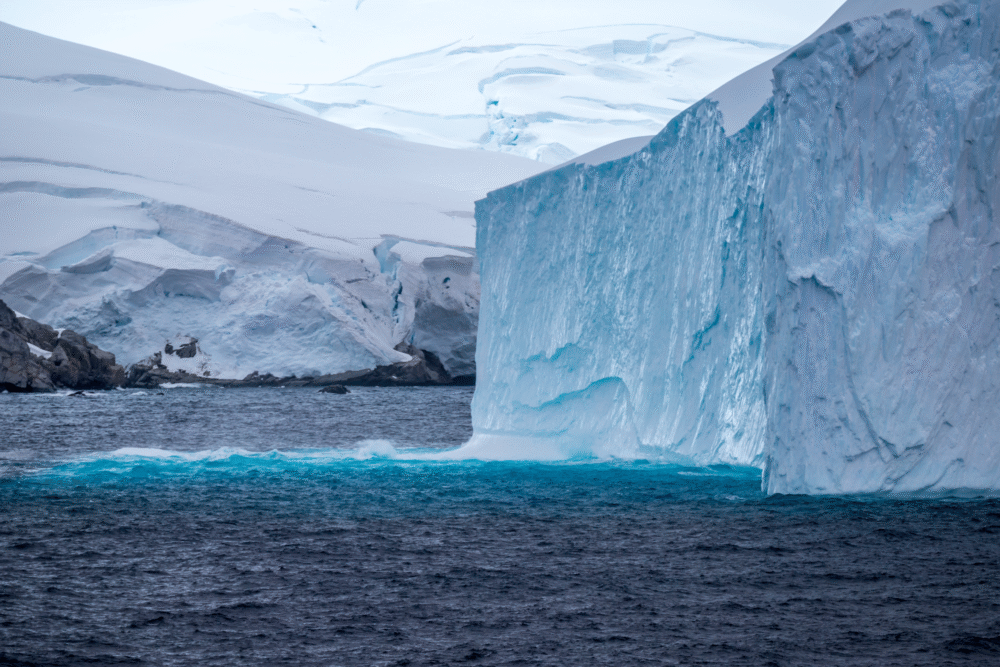

3. Ice shelf “buttresses” that stabilize the glacier are crumbling.

Glaciers like Thwaites are partially stabilized by floating ice shelves that act like buttresses, slowing the glacier’s slide into the sea. But those buttresses are now cracking and breaking up. The Pine Island and Thwaites ice shelves have already lost huge chunks. These fractures reduce the friction holding the main glacier in place.

Scientists liken it to losing the brakes on a massive conveyor belt of ice. Without that support, Thwaites can flow more freely—and dangerously—into the ocean. Glaciologist Erin Pettit of Oregon State University explained, “The glacier is like a house of cards. Once one part goes, the rest can come crashing down.”

This accelerating collapse is why researchers are rushing to monitor every movement. If the shelves vanish completely, it could be the tipping point for a full-scale retreat.

4. The collapse could destabilize the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Thwaites acts like a keystone in the arch of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. If it collapses, neighboring glaciers like Pine Island, Haynes, and Smith could follow suit. Together, this region holds enough ice to raise sea levels by up to 10 feet.

That’s not a distant possibility—it’s a real risk this century if current melting trends continue. The architecture of the ice sheet is interconnected, and once the balance is lost, it’s almost impossible to restore. Feedback loops like ice cliff collapse and marine ice sheet instability could accelerate the unraveling.

The big fear among glaciologists is that this won’t be a gradual event—it could unfold in stages, but much more rapidly than humans are prepared for. In a world already grappling with extreme weather, this would push climate adaptation beyond its limits.

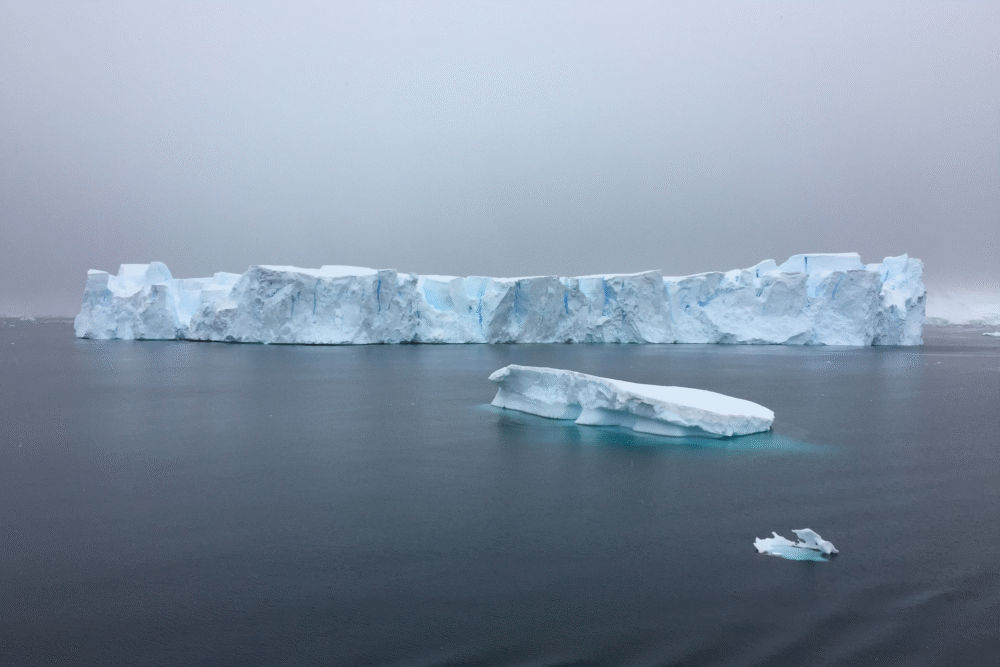

5. Massive cracks and crevasses are forming across Thwaites’ surface.

Satellite imagery and drone footage have revealed dramatic changes to Thwaites’ surface in recent years. Crevasses and rift lines are now crisscrossing areas that were once stable. These cracks signal internal stress as the glacier shifts and destabilizes.

One crack alone can be miles long, growing wider each month. When these fractures link up, they can create massive calving events—where entire icebergs break off. These aren’t minor features; they’re indicators that the glacier is reaching a structural breaking point. What’s more alarming is the speed of this change.

What used to take centuries is now unfolding in decades. Scientists at the British Antarctic Survey say the glacier’s surface is “becoming increasingly fragmented,” a clear warning that its collapse is accelerating, not slowing.

6. Warm ocean water is flowing farther beneath the glacier than expected.

Recent expeditions using sub-ice autonomous vehicles like Icefin have revealed something startling—warm ocean water is penetrating deeper into Thwaites’ grounding zone than previously recorded.

This grounding zone is where the glacier transitions from land to sea, and it’s vital for stability. If water infiltrates too far, it can lift the glacier off the seabed, reducing friction and allowing it to flow more rapidly into the ocean.

Dr. Britney Schmidt, an associate professor at Cornell University, explained, “The warm water is sneaking in under the glacier and making it more unstable from below than we thought.” This unexpected heat flow is one of the most worrying signs yet. It means that even in freezing air temperatures, ocean-driven melting could continue unabated, hastening the collapse.

7. Thwaites may already be in irreversible retreat.

Some scientists believe Thwaites has already passed a point of no return. That means no amount of intervention—short of geoengineering—will stop it from melting back over the coming decades. Once a glacier begins irreversible retreat, gravity and internal stress take over.

Even if emissions stopped tomorrow, the glacier would keep flowing toward the ocean. This is not just theoretical; geological evidence shows similar patterns from ancient ice loss events. The last time Earth saw widespread glacier retreat at this scale, it triggered massive sea level changes.

We’re seeing similar signals now—loss of mass, thinning, grounding line retreat, and structural fractures. If Thwaites really is beyond saving, the world has far less time to prepare for its consequences than anyone hoped.

8. Cities across the globe would face intensified flooding.

If Thwaites collapses fully or even partially, sea levels could rise dramatically, intensifying storm surges and tidal flooding in cities worldwide. Places already dealing with sunny-day flooding—like Miami and Jakarta—would experience far worse.

Protective infrastructure like levees and seawalls would be overtopped or rendered obsolete. Insurance rates would skyrocket, low-lying communities would face displacement, and coastal economies would suffer deep losses. In the U.S. alone, over 13 million people live in areas that could flood with just a two-foot rise.

That figure grows exponentially as neighboring glaciers collapse. Thwaites may sit in a remote corner of the world, but the ripple effects of its demise would crash ashore everywhere—from Sydney to San Francisco to São Paulo.

9. Thwaites is melting five times faster than it was in the 1990s.

According to data from NASA’s Operation IceBridge and the European Space Agency’s CryoSat, Thwaites has lost over 1,000 billion tons of ice since the 1990s. Its rate of mass loss has quintupled.

Scientists attribute this to a combination of warming ocean temperatures, collapsing ice shelves, and increasingly unstable grounding lines. The numbers are staggering—and getting worse. This isn’t a slow trickle. It’s a dramatic acceleration of ice discharge.

Experts like Eric Rignot from the University of California, Irvine, say the current pace of melting “is not sustainable and will likely lead to a major restructuring of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.” If current rates continue—or speed up—the timeline for serious sea level rise will shorten drastically, leaving global cities with far less time to adapt.

10. The collapse of Thwaites could trigger a climate panic domino effect.

Beyond the physical damage, a sudden, visible collapse of Thwaites could trigger a global psychological and economic shock. Markets tied to coastal real estate, global shipping, agriculture, and insurance would respond swiftly.

Governments would be forced to act rapidly, diverting emergency resources and rethinking infrastructure priorities. Panic migrations from vulnerable regions could become the norm. A single event—say, a huge iceberg breaking off—could make the climate crisis feel very immediate and very real.

Some experts worry that this kind of moment could either galvanize international cooperation or fuel division and fear. Either way, the collapse of Thwaites wouldn’t just reshape coastlines—it could reset humanity’s sense of climate urgency in a way we’ve never seen before.