A timeless human idea shows up again and again in ancient stories, long before the Christian era.

When people hear “resurrection,” they often think of Christianity first. But the basic idea of death followed by return, renewal, or rebirth is far older and shows up across many cultures.

These stories weren’t all saying the same thing. Some focus on a god who returns, others on seasonal cycles, and others on a future restoration after catastrophe. What they share is a stubborn human hope: death isn’t the final word.

Below are some of the clearest, best-documented examples that predate Christianity, plus what they may reveal about how ancient people made sense of life and loss.

1. The resurrection idea is older than any single religion

Long before modern religions formed, people told stories that linked death to renewal. In many places, the pattern shows up alongside farming, kingship, and the changing seasons—things ancient communities depended on to survive.

That’s why it helps to think in themes, not headlines. Some myths describe a literal return to life. Others describe a return in power, a seasonal comeback, or a future reappearance after an apocalypse. The details vary, but the emotional question is the same: what comes after loss?

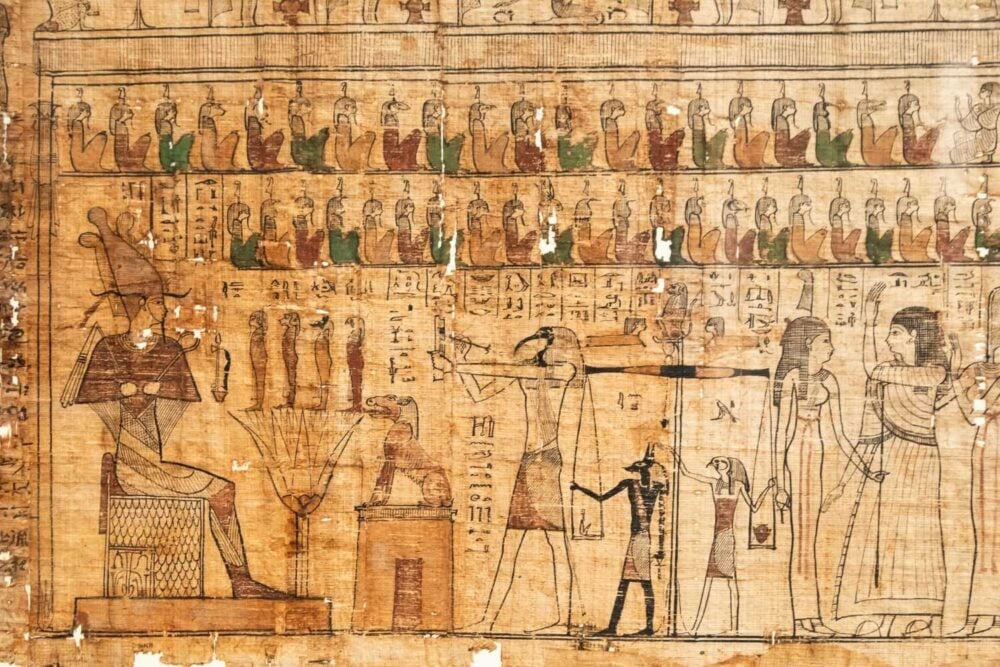

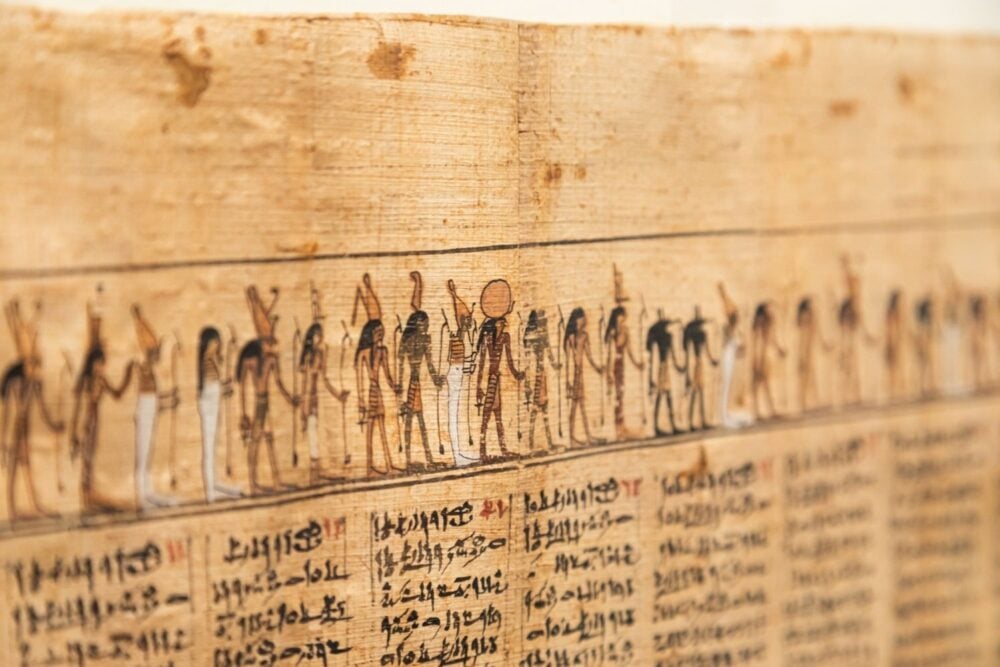

2. Osiris became a symbol of death and renewal in Egypt

In ancient Egypt, Osiris is tied to both fertility and the afterlife, and he becomes a model for the dead and “resurrected” king. In many tellings, he is killed, restored in a way that allows new life to continue, and then reigns in the realm of the dead.

What matters is the message the myth carried. Death did not erase order. It transformed it. Osiris became a bridge between endings and continuity, and his story shaped how Egyptians imagined kingship, burial, and hope beyond the grave.

3. Inanna and Ishtar return from the underworld

In Mesopotamian tradition, the goddess Inanna (and later Ishtar) descends to the underworld and, in the story, returns to the world above. The myth connects underworld movement to the rhythm of fertility and life on Earth.

The twist is that the underworld has rules. Coming back isn’t free. The journey is framed as dangerous, costly, and negotiated. That tension is part of what makes the story feel so human: the return happens, but it leaves consequences behind, like a shadow that follows the light.

4. Tammuz and Dumuzi are tied to seasonal grief and return

Tammuz (Akkadian) and Dumuzi (Sumerian) are linked to cycles of loss and renewal. Ancient worship included festivals—one celebrating marriage, another lamenting death—showing how communities ritualized the swing between life’s fullness and life’s absence.

In stories connected with Ishtar’s descent, the underworld bargain often involves a substitute, and Tammuz/Dumuzi becomes tied to the logic of “returning” only part of the time. That seasonal structure helped people explain why the world blooms, fades, and blooms again.

5. Adonis became a clear “death and revival of nature” story

The myth of Adonis centers on a youthful figure whose death and “resurrection” represent nature’s decay and return. Ancient festivals called Adonia commemorated him, aiming to support vegetation growth and rain—practical concerns wrapped in sacred storytelling.

This is a good example of how “resurrection” language can mean different things. Sometimes it’s about a person returning. Sometimes it’s about the world returning. In Adonis, the emotional center is the same: life disappears, then somehow comes back, and people cling to that pattern.

6. Persephone’s return explains the seasons in Greek myth

Persephone’s story isn’t usually told as “resurrection,” but it is a powerful return-from-death motif. She is taken to the underworld, and her time below becomes linked to the earth’s barrenness, while her return is linked to renewal and growth.

The myth works like a calendar with emotions. When Persephone is gone, Demeter grieves and the world withers. When she returns, life comes back. It’s a story that turns seasonal change into a family drama—loss, waiting, reunion—so everyone can feel it.

7. Dionysus is “twice-born,” a different kind of comeback

Dionysus is famous in Greek tradition as “twice-born.” In one major strand, he is saved and born again after disaster, which becomes part of his identity and cult story.

This isn’t the same as a one-time return from the tomb. It’s more like a sacred reboot—life preserved, life restored, life reintroduced. That matters because it shows how ancient people played with the boundary between death and life in multiple ways. Sometimes the miracle is “coming back.” Sometimes it’s “not being fully erased” in the first place.

8. In Norse myth, Baldr’s story points to a return after Ragnarök

Baldr’s death is one of the most famous tragedies in Norse mythology, and Ragnarök is the catastrophic end of the world in those stories. What’s striking is that the tradition also includes renewal afterward—a rebuilt world and a restored order.

Some tellings include Baldr returning after Ragnarök to be part of the new age. That idea matters because it’s not just personal resurrection. It’s cosmic. The world dies, then returns. The hope is not “nothing ends,” but “something begins again, even after the worst ending imaginable.”

9. Many of these myths were built for survival, not trivia

It’s tempting to treat these stories like a list of “who came back,” but ancient communities used them to cope with real fears. Crops failed. Winters killed. Epidemics came. People needed a story that said renewal was possible.

That’s why so many return-from-death motifs cluster around farming seasons, kingship, and sacred rites. The myths gave emotional order to a risky world. They taught patience during loss and offered a script for grief: mourn, endure, and watch for the return—of spring, of stability, of life itself.

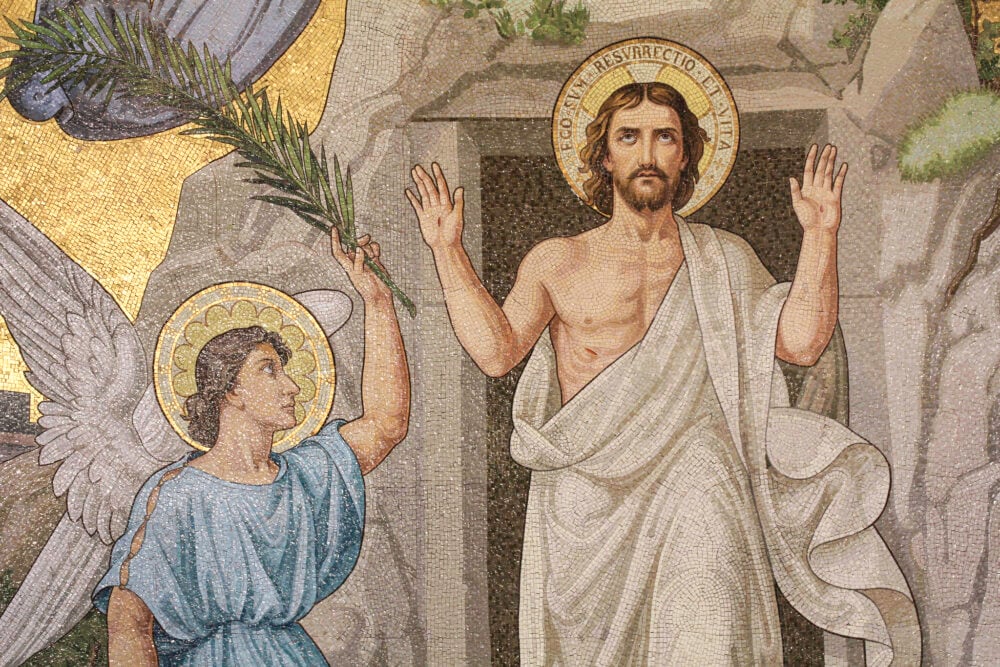

10. Similar theme, different claims: mythic cycles vs historical faith claims

It’s also important to be fair about categories. Many pre-Christian stories are mythic narratives tied to ritual cycles and symbolic renewal. Christianity, by contrast, frames Jesus’s resurrection as a real event in history within its faith tradition, not just a seasonal metaphor.

So the comparison isn’t “same story, different name.” It’s “shared human longing, expressed differently.” Looking across cultures doesn’t erase differences. It highlights how often humans reach for the same hope—then build very different meanings on top of it, depending on place and time.

11. Why resurrection stories still grip us today

Even now, people are drawn to comeback stories because they speak to the fear underneath everyday life: that loss is final. Resurrection myths don’t just promise a miracle. They promise that meaning can survive the worst thing.

That’s why these ancient stories keep resurfacing in books, films, and modern spirituality. Whether you read them as literal, symbolic, or psychological, they carry the same message ancient listeners needed: darkness happens, but it may not be the end of the story. And for many people, that idea is powerful enough to last for millennia.