What you recall is often shaped by what you needed to forget.

Memory feels solid. You think back and see the moment clearly—what you said, how they looked, where you stood. But memory isn’t a recording. It’s a reconstruction. And every time you revisit it, your brain smooths edges, fills gaps, and adjusts the story just enough to make it bearable. That doesn’t mean you’re lying to yourself. It means your brain is doing its job: protecting you.

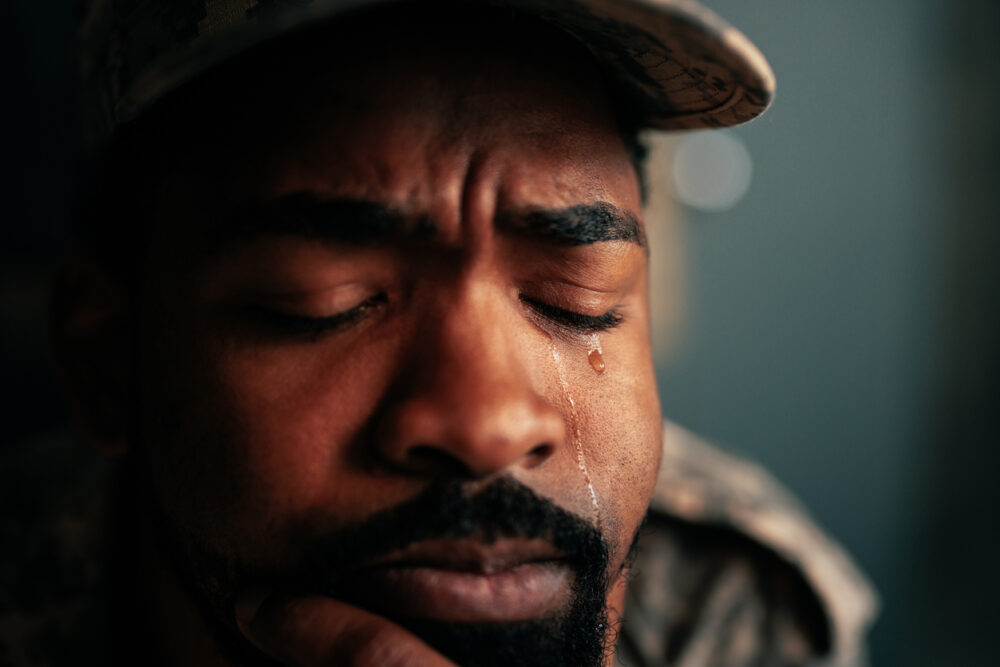

Some memories sharpen with pain. Others blur into something less threatening. Sometimes we exaggerate. Sometimes we erase. And most of the time, we don’t even know we’ve done it. What stays isn’t always what happened—it’s what we needed to keep. This isn’t a flaw. It’s a survival tool. Memory is emotional, not neutral. It keeps what helps you function and hides what doesn’t. These aren’t just forgetful moments or warped perceptions. They’re quiet edits made for your protection, whether you asked for them or not.

1. Your brain edits painful memories to make them easier to carry.

When something hurts too much, your brain doesn’t just store it—it reshapes it. You might forget specific details, soften someone’s words, or misplace the timing. Joyce W. Lacy and Craig E. L. Stark explain in Trends in Neurosciences that memory isn’t a perfect recording device—emotionally charged experiences often get reshaped over time as the brain prioritizes emotional regulation over precision. Remembering isn’t just about keeping the past intact. It’s about making the present livable.

You may recall that a breakup was mutual, even if it wasn’t. You might downplay how afraid you felt in a moment that terrified you. These aren’t lies—they’re adaptations. When memories threaten your sense of stability or self-worth, your brain adjusts the sharpness. Pain still leaves its mark, but it becomes more manageable. The cost? A story that’s easier to carry, but not always true.

2. Strong emotions reshape how you remember what happened.

When you’re overwhelmed—angry, terrified, elated—your brain doesn’t record the moment like a photograph. It records it like a flash. In Scientific American, Ingfei Chen highlights how emotionally intense moments tend to sharpen certain details while dulling others, leading to memories that are vivid but uneven. You remember the slam of a door, but not the conversation before it. You recall a look, a tone, a phrase—but not the full context.

Later, your brain tries to fill in the blanks. It reconstructs the memory based on emotional weight, not factual balance. That’s why two people can live through the same event and remember it completely differently. They’re not lying. Their brains just prioritized different pieces of the moment. Emotion tells your brain what’s important, and memory follows its lead—even if that means distorting the full picture.

3. You unconsciously rewrite your own role in the story.

It’s common to look back on a difficult moment and see yourself differently than you were. Sometimes you paint yourself as the hero, other times the victim. You might leave out the parts where you were confused, reactive, or unsure. That’s not ego—it’s self-preservation. Lisa Bortolotti and Ema Sullivan-Bissett argue in Mind & Language that memory often bends in service of identity, helping maintain a stable sense of self even when it means distorting the details.

This can look like forgetting what you said during an argument, or overemphasizing someone else’s reaction while minimizing your own. Memory isn’t just about events—it’s about coherence. Your brain wants the story of you to make sense. So it edits the past to preserve the present version of who you believe you are. The goal isn’t accuracy—it’s stability.

4. Details you don’t emotionally attach to are the first to fade.

Not all forgetting is trauma-based. A lot of it is just emotional triage. Your brain doesn’t bother saving details that didn’t matter much to you at the time.

The background music, what someone wore, what street you turned on—if it didn’t hit you emotionally, it didn’t get tagged as important. And if it wasn’t important, your brain let it go. This is why some memories feel like fragments. You can remember exactly what someone said, but not where you were. You recall how you felt, but not what happened afterward. Your brain’s memory system prioritizes meaning, not completeness. It saves what shaped you and skips the rest. You’re not forgetful. You’re efficient—just not in the way you think.

5. Repetition changes memory more than time does.

The more you retell a story—even to yourself—the more you rewrite it. Each time you recall a memory, your brain reconstructs it from scratch, not from a permanent file. And with each reconstruction, tiny edits get baked in. You emphasize certain parts, leave out others, add bits you picked up later. Over time, those edits become the memory.

This doesn’t mean the whole thing is false. It means that memory is alive. It shifts with how you talk about it, who you tell it to, and what parts feel safe to include. The danger isn’t in forgetting—it’s in repetition that feels solid but slowly distorts. You can still believe what you’re saying. But know that memory is shaped less by time passing than by how often—and how emotionally—you’ve revisited it.

6. Your brain hides things it doesn’t think you’re ready to process.

Some memories don’t disappear—they just get buried. Not because they’re unimportant, but because they’re overwhelming. Your brain has systems for repression—not to deceive you, but to protect you until it thinks you can handle what’s been stored away.

This isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s subtle. A moment you brushed off. A comment that stung more than you admitted. A night that doesn’t come back clearly no matter how hard you try.

These gaps aren’t accidents. They’re boundaries. Your brain drew a curtain, not to erase the experience, but to soften its weight. When you finally remember something later, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t real. It means your body decided now was the safer time to face it. Memory doesn’t operate on accuracy. It operates on timing—and self-preservation.

7. Memories from childhood are shaped more by emotion than fact.

You don’t remember your early years in a straight line. You remember snapshots—moments that felt big, confusing, or intense. A glance. A tone of voice. The way someone made you feel, even if you didn’t understand why. Your brain was still learning how to form memories, so what stuck wasn’t the whole story. It was whatever made you feel safe, scared, loved, or alone. That’s why childhood memories can be both vivid and vague. You might remember how a room felt but not what was said. You might carry deep emotional truths with no clear explanation.

These aren’t false memories—they’re emotional ones. Your brain stored the mood before it knew how to store the timeline. That can make revisiting the past disorienting. It’s not just hazy—it’s tilted toward what mattered most to you at the time, whether or not anyone else noticed.

8. Memory blends together similar experiences to reduce stress.

Your brain likes efficiency. When you’ve had multiple experiences that feel emotionally similar—say, repeated arguments, patterns in relationships, or cycles of rejection—it often compresses them into one generalized memory. You might struggle to remember when something happened or who said what, because your brain grouped it all under the same emotional file: unsafe, unwanted, overwhelmed.

This isn’t laziness—it’s compression. Repetition sends the signal that the details don’t matter, only the outcome. And so you remember the feeling more than the facts. This is especially common in patterns of emotional harm or instability. Your brain reduces the load by skipping the timeline and reinforcing the takeaway. You didn’t forget the details to protect someone else. You forgot them to protect yourself from reliving the whole thing every time.

9. Guilt distorts memories just as much as denial.

When you feel guilty about something—whether it’s a reaction, a choice, or something you didn’t do—your memory of the event becomes distorted. You might exaggerate your responsibility or minimize what was done to you.

Guilt reshapes the narrative to focus on your role, even when you weren’t the only one involved. This distortion often looks like self-blame. You replay moments over and over, searching for what you “should have” done differently.

Your brain fixates on control because guilt gives the illusion that you could’ve changed the outcome. But memory shaped by guilt rarely gives you clarity. It gives you punishment. And it keeps you stuck in a loop of self-surveillance instead of resolution.

10. Trauma time makes memory nonlinear.

Trauma interrupts the usual flow of time in the brain. During overwhelming events, the systems that create narrative memory can go offline. That’s why traumatic memories often feel fragmented or stuck. You might not remember what happened before or after. You might relive the moment unexpectedly or feel like it’s happening in the present, even if it’s years behind you.

This isn’t just emotional—it’s neurological. Trauma memory is stored differently. Instead of a clear timeline, you get flashes, sensations, or body memories. You remember the fear, but not the order. You remember the sound, but not the words. And that can make you doubt yourself. But fractured memory isn’t fake memory. It’s your brain doing the best it can to record what felt impossible to process in real time.

11. The mind preserves the version that helps you keep functioning.

At the end of the day, memory doesn’t serve truth—it serves continuity. Your brain will often protect you from what would destabilize you, even if it means distorting, deleting, or simplifying.

You remember enough to move forward. Enough to stay coherent. Enough to keep going. The cost is precision. The benefit is survival. Sometimes the version of the past you’re holding is gentler than what really happened. Sometimes it’s harsher. Either way, it’s not accidental. It’s a structure built to carry you. And when you’re finally ready—mentally, emotionally, physiologically—that structure may shift. The memory may sharpen, change, or return in a new form. Not to hurt you, but to invite integration. Your mind didn’t fail you. It protected you, exactly when and how you needed.