Scientists aren’t just dreaming—these lost species might actually walk the earth again.

You might think once an animal goes extinct, it’s gone forever. But thanks to mind-blowing advances in DNA technology, that “forever” is looking a lot shorter. Scientists are now digging into ancient bones and frozen carcasses, pulling out genetic material and asking, “What if we could bring them back?” And honestly, they just might.

We’re talking about the real possibility of seeing mammoths stroll across tundras again or hearing the eerie call of birds long silenced. It’s like Jurassic Park—without the velociraptors (we hope). If these projects work, we could be entering a new era where extinction isn’t a full stop—it’s just a pause. Here are 11 animals that could make the ultimate comeback—and what it means for the planet (and our curiosity).

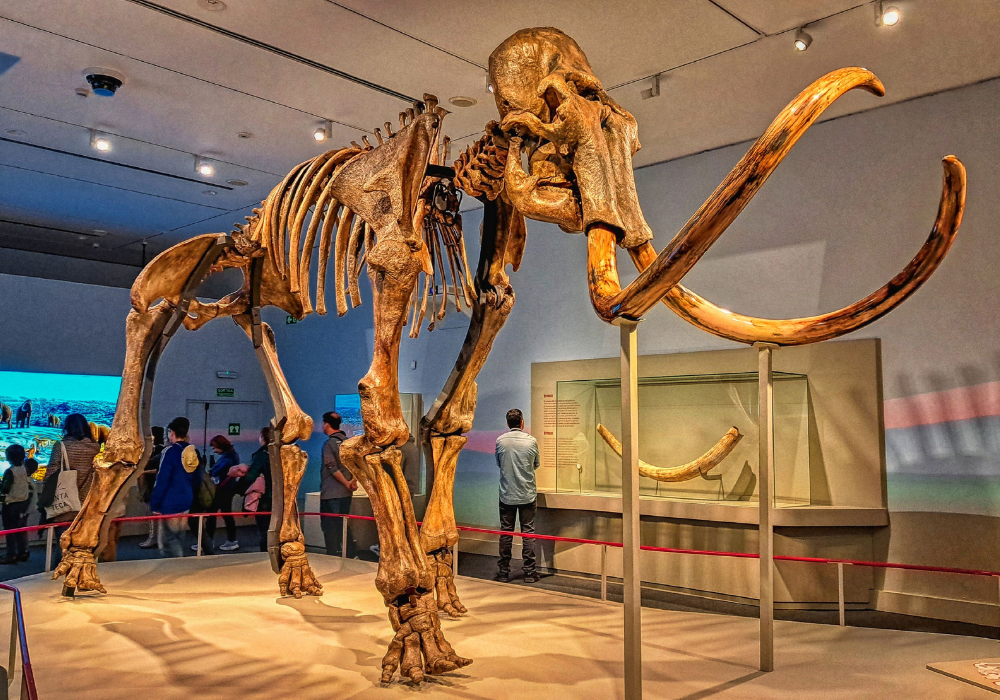

1. The woolly mammoth may soon be stomping across the Arctic again.

Scientists have been obsessed with the woolly mammoth for years, and it’s easy to see why. It’s huge, furry, iconic—and we actually have well-preserved specimens from the permafrost, complete with usable DNA. The goal isn’t to clone a perfect copy but to engineer a cold-adapted elephant with mammoth traits using CRISPR. If it works, the mammoth could help restore grasslands in Siberia, potentially slowing permafrost melt and climate change.

It’s wild to think an extinct Ice Age giant might become a modern environmental ally. The ethics? Complicated. But the tech? Already moving fast. And if this succeeds, the woolly mammoth might be just the beginning.

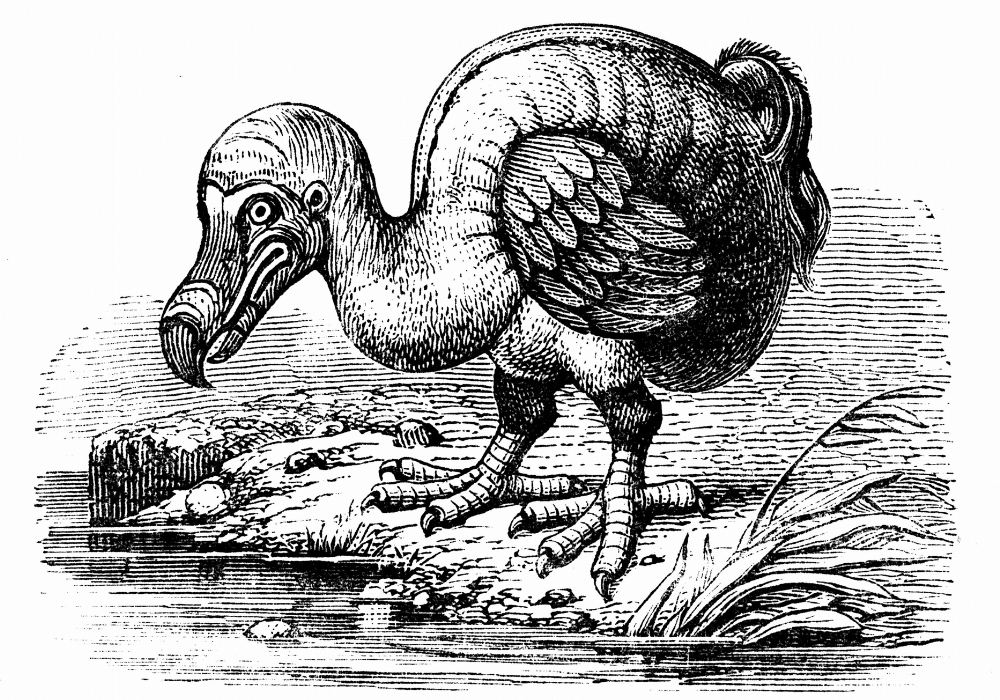

2. The dodo could finally get its revenge on history books.

The dodo has become a symbol of extinction—mocked, misunderstood, and sadly gone. But scientists are working to change that narrative. With access to DNA from dodo bones and a close living relative—the Nicobar pigeon—researchers believe they could revive this flightless bird. It wouldn’t be a clone, but a hybrid with dodo-like traits. The idea isn’t to repopulate Mauritius but to show that we can undo past human-caused damage.

It’s weirdly poetic: humans caused the dodo’s extinction, and now we might bring it back. Maybe someday school kids won’t learn about the dodo as a cautionary tale, but as a success story in resurrection biology.

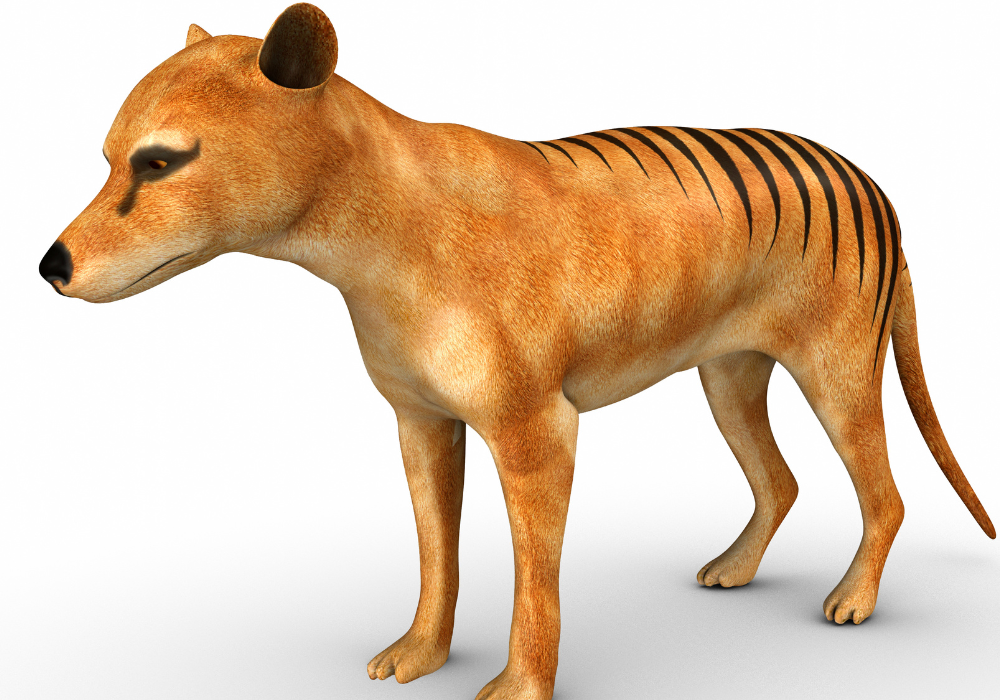

3. The Tasmanian tiger might prowl the bush once again.

Also known as the thylacine, this striped marsupial carnivore went extinct in the 1930s. But scientists at multiple universities are deep into de-extinction research, using thylacine DNA preserved in museum specimens. Australia still has the right habitat, and its closest living relative—the numbat—offers genetic clues for reconstruction.

If they succeed, the Tasmanian tiger could be reintroduced to control invasive species and restore balance to fragile ecosystems. There’s public support, too—Australians are obsessed with the thylacine. It’s like their lost national icon. Reviving it would be more than scientific bragging rights; it’d be a deeply emotional win.

4. The passenger pigeon could repopulate forests in giant flocks.

Once numbering in the billions, passenger pigeons were wiped out by hunting and habitat loss by the early 1900s. But we have well-preserved DNA, and their closest living relative, the band-tailed pigeon, could serve as a genetic template. Scientists hope to edit band-tailed pigeon embryos to produce a new, flock-loving version of the extinct bird.

Why bring them back? These pigeons were forest architects—fertilizing soil and spreading seeds. Their absence changed entire ecosystems. If they return, it’s not just about nostalgia—it’s about restoring balance to forests that haven’t been the same since they vanished.

5. The great auk might return to chilly northern coasts.

This flightless seabird looked like a cross between a penguin and a puffin—and once roamed the North Atlantic in huge numbers. Overhunting led to its extinction in the mid-1800s. But researchers are eyeing the razorbill, its closest cousin, to help recreate the great auk’s genome.

Bringing it back wouldn’t just be cool for bird lovers—it could help restore marine ecosystems disrupted by its loss. Plus, it’s a stark reminder of how fast we can destroy a species—and how we might have the tools to fix it. Watching a great auk waddle around again would feel like flipping the script on history.

6. The Pyrenean ibex was already cloned once—and it could happen again.

This muscular, wild mountain goat from the Pyrenees officially went extinct in 2000. But in 2003, scientists made history by cloning it—marking the first (and only) time an extinct animal was brought back to life, even briefly. Sadly, the baby ibex died shortly after birth due to lung defects. Still, the experiment proved resurrection was possible.

Now, researchers have better cloning techniques and are hopeful they can try again with higher success. The Pyrenean ibex could be the first extinct animal to be truly re-established—and if it works, the door opens for dozens more.

7. The quagga might trot across African plains again.

At first glance, the quagga looked like a zebra with a serious identity crisis—striped in the front, solid in the back. It was hunted to extinction in the 1800s. But scientists realized it wasn’t a separate species—it was a subspecies of the plains zebra. That meant it wasn’t gone forever, just genetically diluted.

Through selective breeding of zebras with quagga traits, the Quagga Project in South Africa has already produced animals that look eerily like the original. Are they “real” quaggas? That’s up for debate—but they’re a stunning example of how DNA and careful breeding can blur the line between lost and found.

8. The Steller’s sea cow might make a comeback from under the sea.

This gentle giant—like a blubbery manatee on steroids—was discovered in 1741 and wiped out by 1768. It only lived in the icy waters near the Commander Islands and was hunted for its meat and fat. Scientists believe they could piece together its genome using preserved bones and tissue samples, then use manatees or dugongs as surrogate species.

If successful, it could be reintroduced into Arctic marine sanctuaries to promote kelp forest health. It’s a long shot, but the idea of these massive sea cows slowly gliding through northern waters again feels like something out of a dream.

9. The Carolina parakeet could bring color and song back to the East Coast.

Bright, beautiful, and once common in the southeastern U.S., the Carolina parakeet was driven extinct by habitat loss and hunting in the early 1900s. It’s the only native parrot species North America had—and we lost it.

But its genome has been sequenced, and scientists are considering editing the DNA of its closest relatives, like the sun parakeet, to revive it. If brought back, it could help pollinate native plants and restore a missing piece of the region’s biodiversity. Imagine hearing their chatter and seeing their neon-green feathers again in southern forests. It’s both nostalgic and wildly hopeful.

10. The moa could tower over us once again in New Zealand.

These flightless birds were like giant ostriches—some species stood up to 12 feet tall! Hunted to extinction by the Māori by the 1400s, moas have fascinated researchers ever since. Their bones are well-preserved, and their closest living relatives, the tinamous of South America, provide a possible genetic base.

If revived, they’d be reintroduced cautiously into protected habitats. It would be surreal to see them lumbering through New Zealand forests again—part prehistoric, part futuristic. Bringing back such a massive creature would be a serious test of de-extinction ethics, habitat readiness, and whether we can truly coexist with what we once lost.

11. The cave lion could stalk northern wildernesses once more.

These big cats weren’t just slightly bigger lions—they were Ice Age predators that roamed across Europe, Asia, and Alaska. Extinct for thousands of years, they’ve been found remarkably preserved in Siberian permafrost, including entire cubs.

Their DNA is intact enough for cloning to be considered. Their closest living relatives are modern lions, which could potentially act as surrogates. While some scientists question the ecological value of reintroducing cave lions, others argue they could help balance ecosystems overwhelmed by herbivores. The idea of hearing a cave lion roar in the Arctic? Terrifying—but also oddly thrilling.