These common misconceptions are stalling the EV revolution for no good reason.

As EV ownership continues to grow, so do myths that muddy the conversation: concerns about driving range, cost, performance, and environmental impact make many drivers hesitant. But these worries often stem from outdated assumptions or cherry-picked anecdotes—not the realities of modern vehicle technology. Today’s electric cars offer impressive acceleration, decent range, and a lower lifetime carbon footprint compared to most gas models.

Charging infrastructure is expanding rapidly, and innovation continues to lower price barriers. Whether you’re curious about switching or trying to understand the hype, it’s time to separate fact from fiction. Clear-eyed answers are crucial for making smart decisions about transportation in an era defined by climate urgency and technological transformation.

1. Electric vehicles are slower and less fun to drive.

Despite early stereotypes of sluggish “golf cart” performance, most EVs offer instant torque and smooth acceleration thanks to electric motors. From mainstream sedans to performance SUVs, EVs can blast from 0–60 mph in under 5 seconds. Models like the Tesla Model 3 or Ford Mustang Mach‑E deliver responsive power that leaves many internal-combustion cars in the dust. The lack of gear shifts means acceleration is seamless, and regenerative braking adds efficiency and control.

What some drivers call “eco mode” can feel anything but underwhelming. And for daily commutes, the quiet cabin and responsive torque create a driving experience many describe as more refined and relaxed than typical gas-powered cars—not less fun.

2. EVs don’t go far enough on a single charge.

Early EVs may have had limited range, but newer models typically travel 250–350 miles per full charge—some exceed 400 miles. That’s comparable to mid-size gasoline vehicles. Most drivers average fewer than 40 miles per day, meaning most charging happens at home overnight—similar to plugging in a phone, not racing to gas stations.

Public charging networks have also grown exponentially, especially along major highways and urban corridors. Fast chargers now deliver up to 200 miles of range in under 20 minutes. Even in long-distance trips, planning remote stops is easier than many expect. Range anxiety is a solvable issue, not a permanent drawback. For many drivers, EV range is more than adequate—and improving fast.

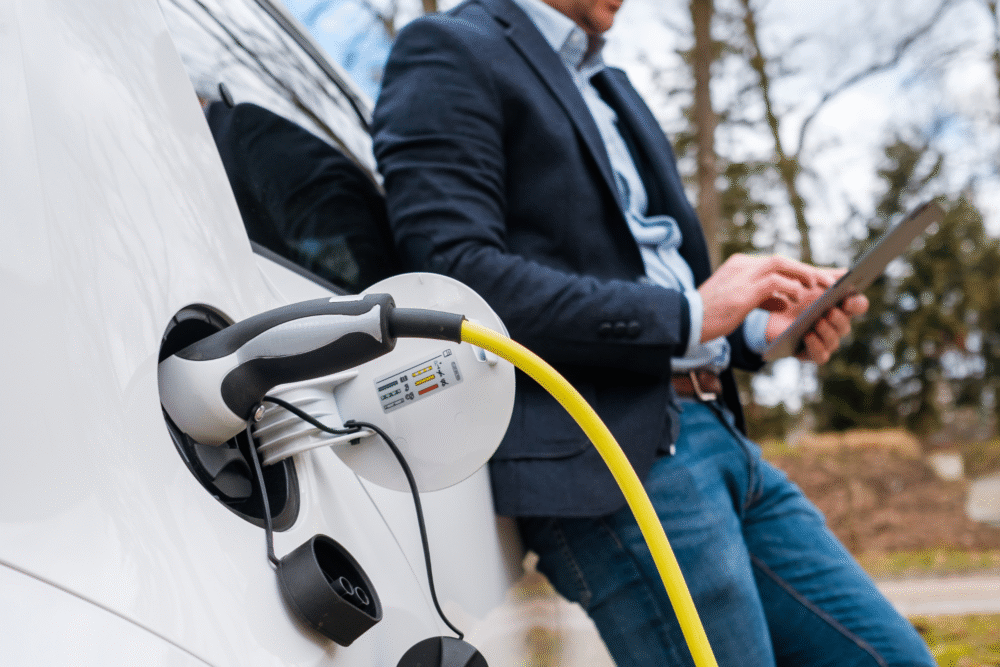

3. Charging is complicated and inconvenient.

Plugging in an EV is straightforward: professionals (or tech-savvy owners) install Level 2 (240 V) home chargers that restore 30–40 miles of range per hour—ideal for overnight charging. Workplaces and public locations support a growing number of chargers. Fast chargers enable quick top-ups while grabbing coffee or stretching lunch. Mobile apps show station availability, wait times, and pricing. Some chargers are free, others cost less than per-gallon gas prices.

There’s also Home-to-Go packages offering affordable installations or bundled electricity plans. Charging is often automated and seamless once set up. While there’s a learning curve, EV charging quickly becomes intuitive—especially compared to scheduling fuel stops or estimating mileage in gas cars.

4. Electric vehicles cost too much to buy.

EV sticker prices used to be significantly higher than gas-powered peers, but costs have dropped dramatically—especially with government incentives. Tax credits, rebates, and lower operating costs narrow the economic gap. Savings on fuel and maintenance (no oil changes or transmission repairs) offset upfront costs.

Some models already cost less than comparable gasoline vehicles. With declining battery prices and growing competition, more affordable EVs are hitting the market. Leasing options also reduce financial barriers. And if gasoline prices stay high, most EV owners recover the cost difference within a few years. When total cost of ownership is considered, EVs are often cheaper over time – not more expensive.

5. EVs are worse for the environment overall.

Many believe electric cars just shift pollution elsewhere. But studies show that even with electricity generated from coal-heavy grids, EV life-cycle emissions are generally lower than fossil-fuel vehicles. And as grids become cleaner, their advantages grow. Battery recycling and second-life uses further reduce environmental impact. Lifetime emission reductions include fewer tailpipe pollutants and less airborne soot.

Urban areas also benefit from cleaner air. Electric vehicles are part of a broader transition to renewables, and their impact multiplies with every avoided gallon of gasoline. If concerns remain, home solar paired with EV charging makes the impact even more positive. Driving electric today is a genuine—and improving—climate benefit.

6. EV batteries wear out and ruin resale value.

While early concerns centered on battery degradation, modern EVs come with warranties protecting battery health for 8–10 years or 100,000+ miles. Most lose only 5–10% capacity over their lifetimes—comparable to phone batteries. And resale values are stabilizing as demand grows. Some older EVs from high-volume brands still hold significant resale value.

Additionally, used EV markets are expanding rapidly, offering lower cost entry into ownership. Technological improvements—like better thermal management and improved chemistries—further limit degradation. Manufacturers also offer second-life uses for aged batteries in energy storage systems. Battery failure is rare and predictable, not catastrophic. This myth misrepresents both modern reliability and the evolving maintenance ecosystem around EVs.

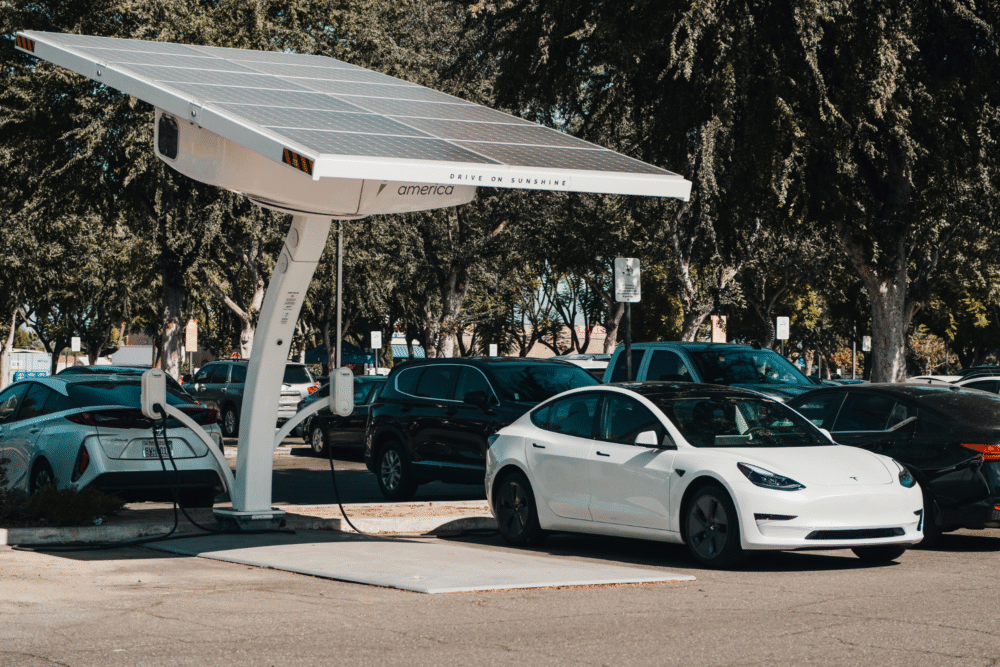

7. Charging infrastructure isn’t widespread or reliable.

This used to be true, but no longer. Charging networks now cover most highways and urban centers in North America and Europe. Public charging locations have grown by tens of thousands in just the past few years. Apps display station compatibility, pricing, and operating hours, making route planning simple. Many fast chargers now operate reliably, and hub locations offer amenities. Chain stores, gas stations, and parking lots also integrate chargers.

Some charging companies guarantee uptime or offer compensation for downtime. Rural coverage is expanding, and communities with high EV adoption often lead installation efforts. Though gaps remain, especially in remote areas, most owners never leave their region without a dependable charging solution—and infrastructure continues to expand rapidly.

8. Extreme weather destroys EV performance.

While cold air can reduce range temporarily, modern EVs manage battery temperatures through thermal systems and preconditioning. Heated seats and cabin warm-up can offset energy loss. In summer, thermal controls and active cooling limit overheating. Charging times remain stable across wide temperature ranges, especially when level 2 or fast-charging stations provide thermal regulation. Winter range loss of 20–30% is real, but predictable and often temporary.

Smart trip planning—with additional buffer—is all that’s needed. EVs in cities like Minneapolis or Edmonton manage cold weather routinely. Meanwhile, diesel vehicles face similar or worse performance drops in extreme cold. In both heat and cold, EVs remain effective with predictable adjustments—just like conventional cars.

9. EVs shift pollution to power plants.

Electric vehicles do draw from power grids—but those grids are growing greener every year. Even in carbon-intense areas, EVs reduce global emissions. Emissions from power generation are easier to regulate and clean up centrally than tailpipe pollution produced everywhere. Renewable energy is increasing; battery storage helps homes pair EV charging with solar or wind.

And many utility companies now offer time-of-use EV plans to encourage charging during periods of surplus clean energy. The net result is lower total emissions and fewer health impacts from local pollutants. Unlike gas engines, EVs don’t emit nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide, or particulate matter at the tailpipe. Pollution isn’t just shifting—it’s decreasing.

10. EVs are just a fad destined to fade.

This myth lingers in part because past innovations—like hydrogen cars—burned out. But electric mobility is backed by massive infrastructure investment, corporate commitments, and consumer demand. Automakers plan more than 50 electric models within the next five years. Governments worldwide are phasing out internal combustion sales by 2035 or earlier. Charging networks, renewable energy, and battery supply chains are scaling fast.

Consumers appreciate EV benefits: quietness, performance, low operating cost, and climate peace of mind. Early adopters are joined by everyday drivers. With falling prices and rising acceptance, EVs are moving past novelty—and becoming the mainstream. Electric vehicle adoption is a systemic shift, not a passing innovation.