Researchers say data removal plan threatens weather forecasting accuracy and public safety during natural disasters.

A growing coalition of scientists and research organizations is voicing strong opposition to a federal proposal that would eliminate public access to decades of climate and environmental data. The plan, currently under review by government agencies, would remove key datasets from public databases that researchers, emergency managers, and weather forecasters rely on daily.

Over 400 scientists from universities and research institutions across the country have signed letters expressing concern about the potential impacts on weather prediction accuracy and disaster preparedness. The data in question includes temperature records, precipitation measurements, and atmospheric monitoring information dating back to the 1980s. Here’s what this controversy means for scientific research and public safety.

1. The proposed plan would remove 40 years of critical climate monitoring data from public access.

Federal agencies are considering a proposal to transfer several major climate datasets from publicly accessible databases to restricted-access systems. The affected data includes temperature records from thousands of weather stations, satellite measurements of atmospheric conditions, and ocean monitoring information collected since 1983.

Currently, this information is freely available to researchers, emergency planners, and the general public through government websites. The proposal cites budget constraints and data management challenges as reasons for the potential changes, but scientists argue the move would severely limit essential research capabilities.

2. Weather forecasting accuracy could decline without access to historical climate patterns and trends.

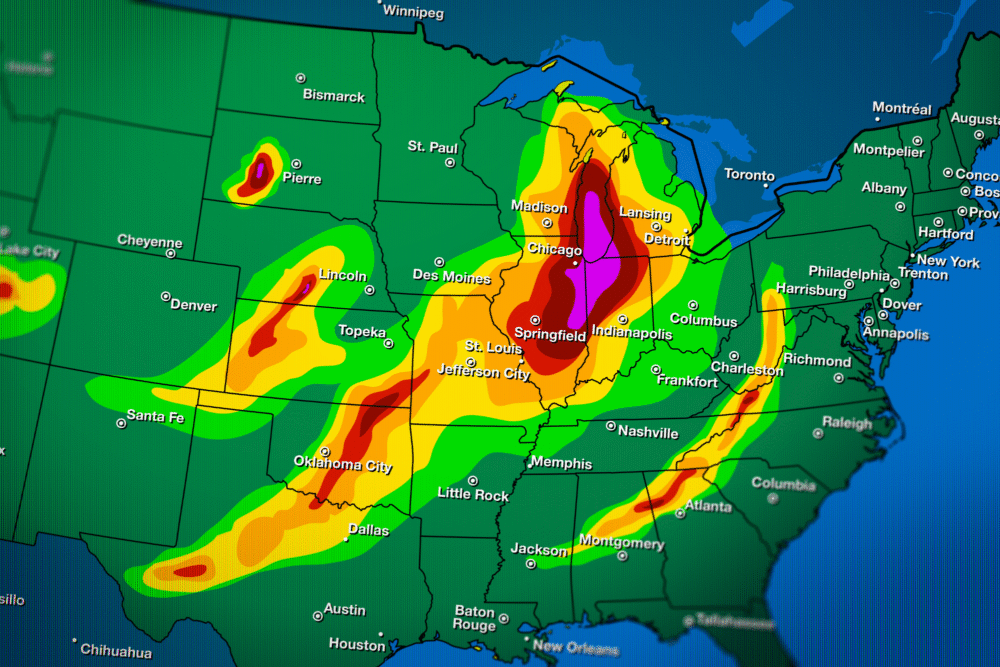

Meteorologists rely heavily on historical data to improve forecast models and understand long-term weather patterns. The National Weather Service uses decades of climate records to calibrate prediction algorithms and identify unusual weather events before they become dangerous.

Dr. Sarah Martinez, an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University, explains that removing this data would be like “asking doctors to diagnose patients without access to medical history.” Emergency managers use historical weather patterns to prepare for seasonal threats like hurricanes, tornadoes, and flooding based on past occurrences.

3. Hurricane tracking and intensity predictions depend on long-term ocean temperature and atmospheric data.

The datasets under consideration include crucial ocean temperature measurements and atmospheric pressure readings that help forecasters predict hurricane formation and strength. These records allow scientists to identify patterns in how storms develop and intensify over warm ocean waters.

Without access to historical comparisons, the National Hurricane Center warns that storm intensity forecasts could become less reliable. This reduction in accuracy could leave coastal communities with inadequate warning time or inappropriate preparation levels for approaching hurricanes.

4. Over 400 scientists from 50 universities have signed petitions opposing the data removal plan.

The scientific response has been swift and coordinated, with researchers from institutions including MIT, Stanford, and the University of Florida joining the opposition effort. The American Meteorological Society and the American Geophysical Union have both issued formal statements expressing concern about the proposal’s potential impacts.

Scientists argue that climate data is a public resource that should remain freely accessible to support research, education, and public safety efforts. The petition signatures represent researchers from diverse fields including meteorology, oceanography, agriculture, and public health.

5. Emergency management agencies rely on this data for disaster preparedness and response planning.

Local and state emergency management offices use historical climate data to develop evacuation plans, position resources, and prepare for seasonal weather threats. FEMA incorporates decades of weather records into flood mapping and disaster risk assessments that determine everything from building codes to insurance requirements. Emergency planners in California use historical drought and wildfire data to anticipate resource needs and coordinate response efforts. Without this information, agencies would struggle to make informed decisions about resource allocation and public safety measures.

6. Agricultural planning and food security assessments would suffer without historical weather records.

Farmers and agricultural researchers depend on long-term climate data to make planting decisions, select crop varieties, and plan irrigation systems. The USDA uses historical temperature and precipitation records to update plant hardiness zones and provide growing recommendations to farmers nationwide.

Climate data helps agricultural economists predict crop yields and identify potential food security risks before they become critical. Removing access to this information could lead to poor farming decisions that affect food production and prices across the country.

7. The data removal could hinder climate research just as extreme weather events become more frequent.

Scientists studying climate change rely on long-term datasets to identify trends and validate research models. The proposed restrictions would limit researchers’ ability to study how weather patterns are changing and what those changes mean for different regions.

This comes at a time when extreme weather events are becoming more common and severe, making scientific understanding more crucial than ever. Graduate students and early-career researchers would be particularly affected, as many lack the resources to access restricted databases.

8. Public health officials use climate data to track disease patterns and prepare for health emergencies.

Health departments monitor relationships between weather patterns and disease outbreaks, using climate data to predict when conditions might favor disease-carrying insects or waterborne illnesses. Heat wave preparation relies on historical temperature data to identify vulnerable populations and plan cooling center operations.

Air quality monitoring programs use atmospheric data to understand pollution patterns and issue public health warnings. Removing public access to this information could delay health officials’ ability to protect communities from weather-related health risks.

9. The proposal could save an estimated $2.3 million annually in data management and server costs.

Government officials cite budget pressures as a primary motivation for considering the data restrictions. Maintaining public databases requires significant computing resources, staff time, and cybersecurity measures that strain agency budgets.

The proposal would transfer data management responsibilities to academic institutions or private organizations that could charge fees for access. Supporters argue that the most essential data would remain available through alternative channels, though possibly with delays or access restrictions that don’t currently exist.

10. International scientific cooperation could be disrupted if American climate data becomes restricted.

Climate research is inherently global, with scientists from different countries sharing data to understand worldwide weather patterns and climate systems. Many international research projects depend on free access to American climate datasets, which are considered among the most comprehensive and reliable in the world.

Restricting access could damage scientific relationships and limit America’s influence in global climate research efforts. Other countries might reciprocate by restricting access to their own datasets, further hampering international scientific cooperation.

11. A final decision on the data removal plan is expected within the next 60 days.

Federal agencies are currently reviewing public comments and scientific input before making a final determination about the proposed changes. The decision timeline has been accelerated due to budget pressures, giving opponents limited time to present alternatives or secure additional funding.

Some scientists are exploring options to mirror the datasets at academic institutions, though this would require significant private funding and technical expertise. The outcome could set a precedent for how the government manages other scientific datasets and public access to research information.