When Earth’s internal compass failed, nature, climate, and civilizations felt the impact.

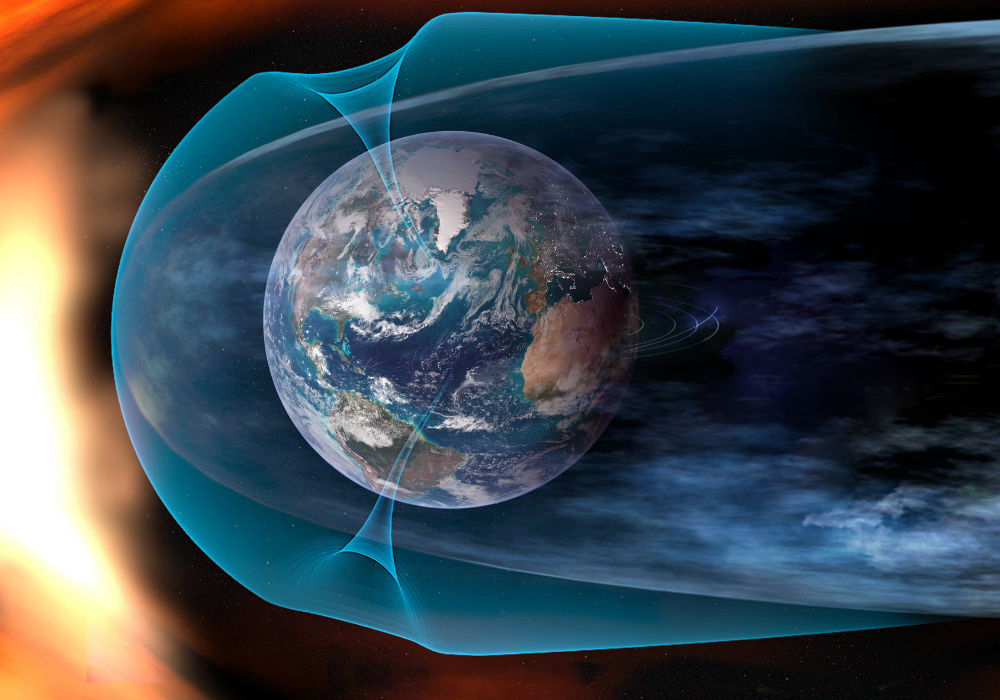

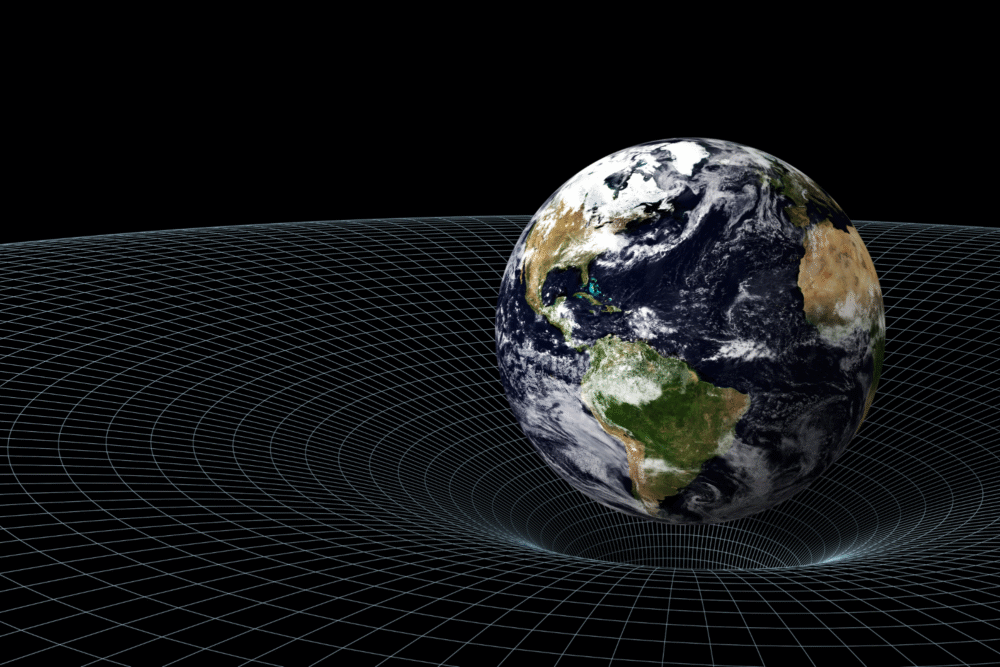

The Earth’s magnetic field isn’t as steady as you might think. Though it usually protects us from harmful cosmic radiation and solar storms, history reveals it can sometimes flip, fade, or falter—throwing the planet into periods of upheaval. These geomagnetic shifts are more than scientific curiosities; they’re deeply tied to major disruptions in Earth’s climate, ecosystems, and even human history.

Sometimes, the field weakens so much that the shield around our planet grows dangerously thin. Other times, the magnetic poles completely reverse, flipping north and south. While we usually measure history by wars and empires, the real story may be hidden beneath our feet—in the churning core that generates this invisible but powerful force. These magnetic meltdowns show just how profoundly Earth’s internal compass has shaped life on the surface.

1. The Laschamp Event nearly erased the magnetic shield 42,000 years ago.

Roughly 42,000 years ago, Earth’s magnetic field dramatically weakened and briefly flipped during what’s known as the Laschamp Event. For about 1,000 years—and especially during a critical 100-year span—the magnetic field lost up to 90% of its strength.

That left the planet exposed to intense solar radiation and cosmic rays. In this vulnerable window, Earth’s climate saw wild swings, ice expanded, and many species suffered. Some scientists even link this event to the extinction of Neanderthals and the sudden spread of symbolic cave art among Homo sapiens, suggesting it triggered a burst of cultural evolution.

The “Adams Event,” as some now call it, shows how even temporary magnetic chaos can ripple through the biological and human record with lasting effects.

2. The Brunhes–Matuyama reversal flipped Earth’s poles 780,000 years ago.

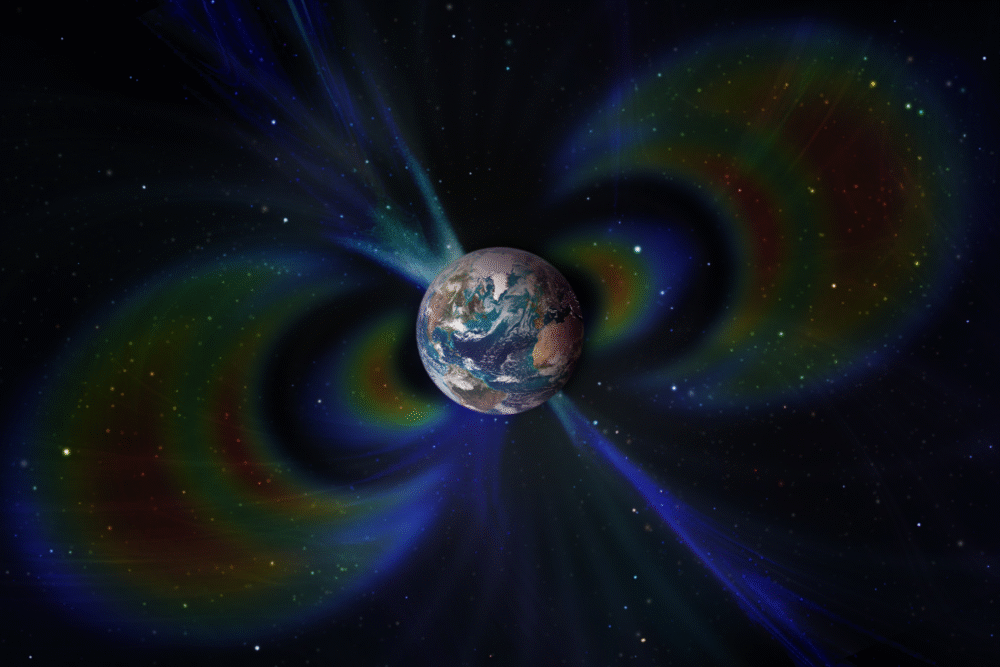

Roughly 780,000 years ago, Earth’s magnetic poles did a full reversal during the Brunhes–Matuyama event, a moment so significant it’s used as a geological timestamp around the world. While the flip itself likely took thousands of years to fully complete, the transitional period saw massive weakening of the field.

That drop in magnetic protection likely increased atmospheric ionization and may have contributed to evolutionary pressures on early hominins. Though no mass extinction followed, the reversal left behind a global layer of magnetic clues in rock and sediment.

Scientists still use this signature to date ancient formations. It’s a powerful reminder that even a slow-motion magnetic flip can change how radiation hits the planet and affect the trajectory of life.

3. The Mono Lake excursion hinted at sudden magnetic instability.

About 34,000 years ago, near what is now Mono Lake in California, Earth’s magnetic field experienced a wild wobble—what scientists call an “excursion.” The magnetic north pole wandered far from its usual place, dipping down to latitudes near the equator before snapping back.

This wasn’t a full reversal, but it still marked a time of magnetic weakness and disarray. Excursions like this don’t last long—often a few hundred years—but they can still thin the planet’s protective field enough to let in dangerous radiation.

These brief magnetic stumbles remind us that Earth’s inner dynamo can behave unpredictably, with cascading effects for climate, weather patterns, and the biological systems sensitive to subtle environmental shifts.

4. The Blake event shook the magnetic field during a volatile ice age.

Roughly 120,000 years ago, in the midst of the last interglacial period, Earth’s magnetic field faltered again. Known as the Blake event, this geomagnetic excursion was marked by erratic shifts in pole position and a weakened field that lasted several centuries.

The timing is critical: it occurred during a period of significant climate instability, and some researchers suggest the weakened magnetic field may have amplified those fluctuations. As ice sheets advanced and retreated, species were forced to adapt quickly—or perish.

While less well-known than full reversals, the Blake event provides more evidence that magnetic instability and climatic upheaval often go hand in hand.

5. The Gauss–Matuyama reversal preceded major evolutionary milestones.

About 2.58 million years ago, the Earth’s magnetic poles reversed during the Gauss–Matuyama event. This flip came at a pivotal moment—the dawn of the Pleistocene Epoch. It was also around this time that early hominins began using more advanced tools and spreading across Africa.

While the reversal itself may not have directly sparked evolutionary leaps, it likely influenced global climate patterns, helping usher in the ice ages that shaped human development. A shifting field can subtly alter the flow of solar radiation and the structure of atmospheric layers, possibly impacting weather and ecological pressures. Coincidence or not, the overlap of magnetic change and human emergence is hard to ignore.

6. The Matuyama–Réunion excursion nearly reversed Earth’s poles.

Approximately 2.14 million years ago, Earth’s magnetic field entered a period of instability during the Matuyama–Réunion excursion. Although it didn’t result in a full pole reversal, the event triggered a steep drop in field strength and a major shift in pole position.

Sediment records show erratic behavior in magnetic alignment, giving scientists a snapshot of Earth’s turbulent core dynamics during this time. It also occurred during a period of climatic cooling, which might’ve been reinforced by reduced magnetic shielding.

Though short-lived, this excursion adds to the pattern: magnetic disturbances—whether total flips or partial wobbles—frequently coincide with ecological and evolutionary shifts.

7. The Cobb Mountain event was a short-lived but telling flip.

Roughly 1.2 million years ago, the Cobb Mountain geomagnetic excursion briefly reversed Earth’s magnetic polarity before returning to its prior state. While lasting only a few hundred years, the event produced enough magnetic instability to leave a signature in geological records.

These short flips don’t usually lead to widespread biological disaster, but they still reveal vulnerabilities. With the field weakened, atmospheric radiation levels can spike, possibly disrupting DNA, reproduction, and ecosystem stability.

What makes the Cobb Mountain event particularly intriguing is how quickly the poles changed and then changed back—suggesting Earth’s magnetic system can behave more like a jittery compass than a stable axis.

8. The Big Lost excursion revealed sudden magnetic chaos.

Around 560,000 years ago, the Big Lost excursion struck during the Matuyama chron, another phase of magnetic volatility. Like other excursions, this one didn’t produce a full reversal but caused the magnetic poles to wander extensively, weakening Earth’s magnetic shield for a significant period.

This instability could have allowed elevated solar and cosmic radiation to reach the surface, impacting early mammalian populations and the broader biosphere. Found in geological records from Idaho and elsewhere, the Big Lost event hints at just how often Earth’s core flirts with chaos. It also underscores how even minor magnetic disturbances can register in the evolutionary and environmental timeline.

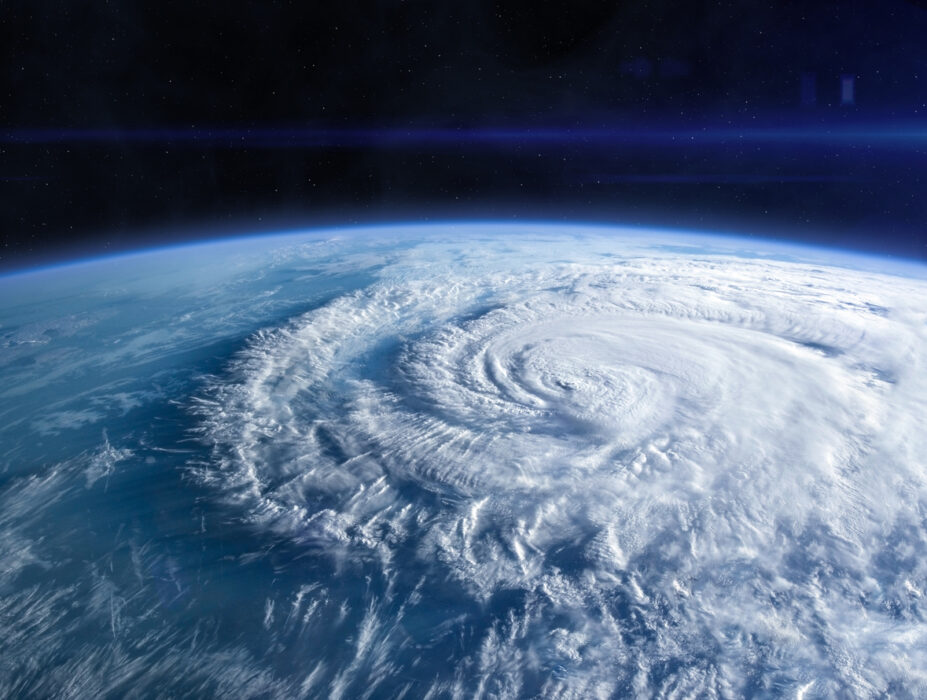

9. The most recent weakening of Earth’s field may signal another flip.

Right now, Earth’s magnetic field is weakening—fast. Over the past 160 years, the field has lost nearly 10% of its strength. The South Atlantic Anomaly, a region where the field is particularly weak, is growing and worrying satellite operators and space agencies.

While we’re not in a full-blown reversal yet, many geophysicists believe we could be on the cusp of one. “It’s not a matter of if the poles will flip again—it’s when,” says Dr. Monika Korte of the GFZ German Research Centre.

A future flip could disrupt power grids, communication satellites, and animal navigation. If past events are any guide, such a shift would have far-reaching consequences, not just for technology—but for biology, weather, and human systems, too.

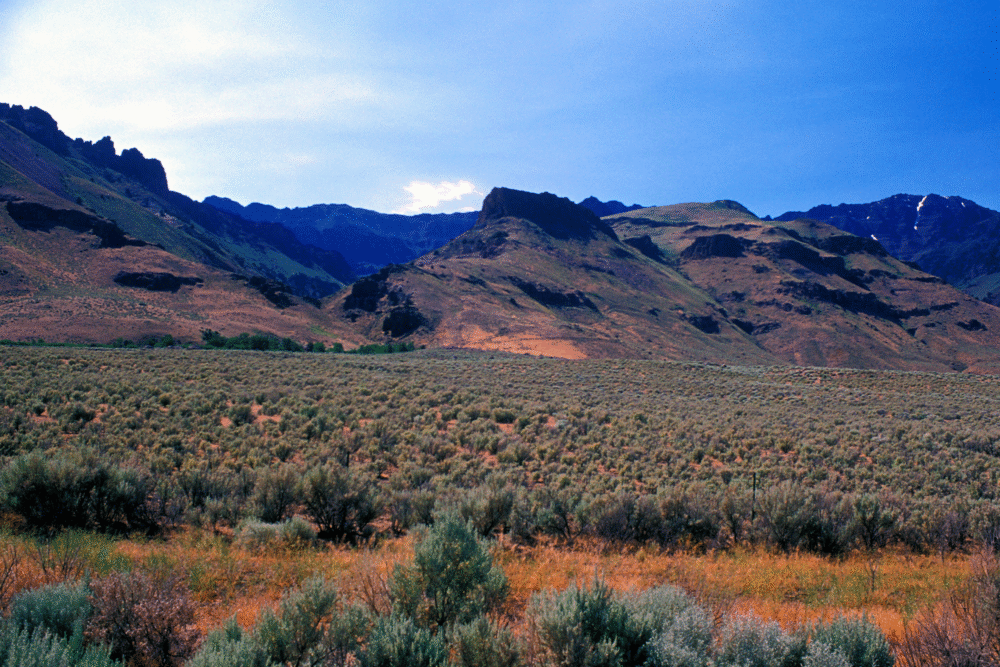

10. The Steens Mountain records revealed magnetic chaos in just a few decades.

In southeastern Oregon’s Steens Mountain, ancient lava flows captured some of the most surprising magnetic shifts ever documented. Around 16 million years ago, during the Miocene Epoch, the magnetic field didn’t just wander—it flipped back and forth dramatically over just a few decades.

Geologists analyzing these flows found that magnetic north shifted by 6 degrees per day during one period. That’s astonishingly fast for a planet-wide force usually thought to move over centuries or millennia. This discovery shattered the assumption that magnetic reversals always take thousands of years.

If such rapid changes occurred once, they could happen again—potentially disrupting electronics, satellites, and biological compasses worldwide. These volcanic rocks serve as a warning etched in stone: Earth’s magnetic field can lurch into chaos far quicker than we ever imagined.

11. The future magnetic flip could blindside modern civilization.

The next magnetic reversal isn’t just a scientific curiosity—it could be a logistical nightmare for our hyper-connected world. A full flip would dramatically weaken Earth’s magnetic shield during the transition, exposing satellites, aircraft, and even power grids to dangerous levels of solar and cosmic radiation.

GPS systems, telecommunications, and internet infrastructure could all be compromised. Birds, whales, and other species that rely on magnetic navigation might lose their way. And because past flips have taken thousands of years, there’s no quick fix—only long-term adaptation.

“The infrastructure we depend on was built with a stable field in mind,” warns geophysicist Dr. John Tarduno. If Earth’s internal compass flips again—as it’s done many times before—we may find ourselves scrambling to adjust to a planet suddenly unmoored.