The planet’s invisible shield vanished—and life on Earth was suddenly exposed to deadly radiation.

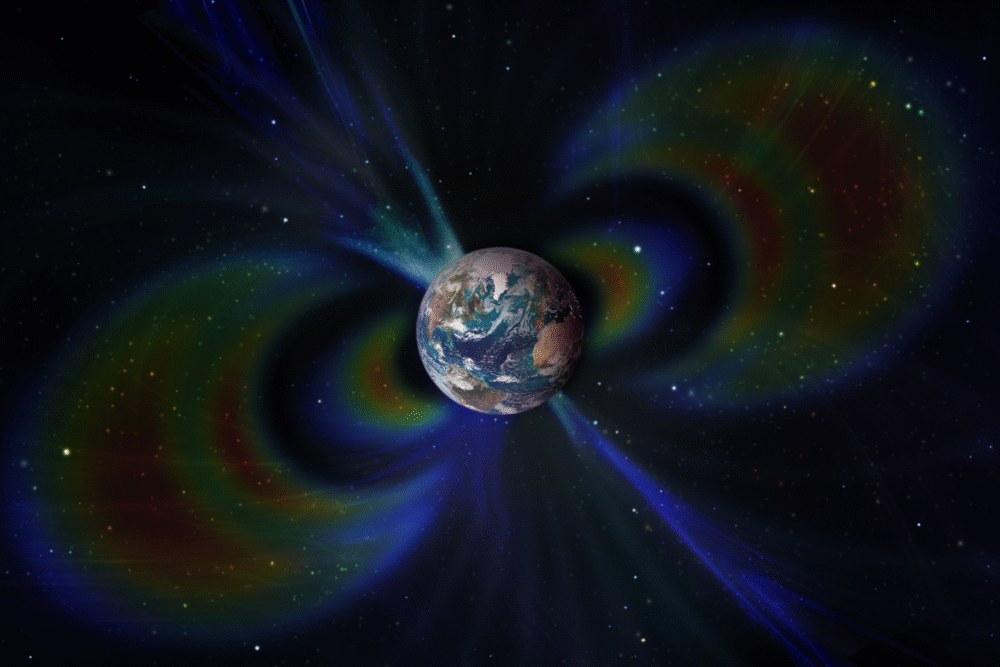

Earth’s magnetic field isn’t just a curious scientific phenomenon—it’s a protective force field that shields us from deadly solar and cosmic radiation. But around 41,000 years ago, during what scientists call the Laschamps Excursion, that shield collapsed. For about 800 years, Earth’s magnetic field weakened to just 5% of its current strength, then flipped poles entirely before returning to normal.

During that collapse, our planet faced exposure levels that could have triggered biological and environmental upheaval. Ancient cave art, extinctions, and climate disruptions all line up with this window of magnetic chaos. If it happened once, could it happen again?

1. The planet’s radiation shield dropped to nearly zero.

During the Laschamps Excursion, the Earth’s magnetic field nearly vanished, dropping to just a sliver of its normal intensity. This field is what blocks harmful solar particles and cosmic rays from bombarding the surface. When it collapsed, Earth lost its shield. Scientists believe radiation levels at the surface skyrocketed, exposing all living creatures—especially those at higher elevations or closer to the poles—to levels of ultraviolet and cosmic radiation that would be considered dangerous today.

This breakdown didn’t just increase health risks; it fundamentally altered atmospheric chemistry, ozone layer thickness, and even weather patterns. For several centuries, life on Earth was far more vulnerable than we ever imagined possible.

2. The magnetic poles flipped, throwing navigation into chaos.

The Laschamps Excursion wasn’t just a weakening—it was a full-blown reversal of the magnetic poles. North became south, and south became north. While animals today rely on the magnetic field for migration, early human ancestors might have also used natural magnetic cues. The reversal likely confused animal migrations, disrupted hunting patterns, and made survival more difficult for both humans and wildlife.

Geomagnetic reversals aren’t like flipping a switch—they unfold over hundreds of years, with the field weakening, wobbling, and reconfiguring. During this instability, Earth became a more dangerous and unpredictable place, with impacts stretching from the biological to the technological—had humans invented compasses by then.

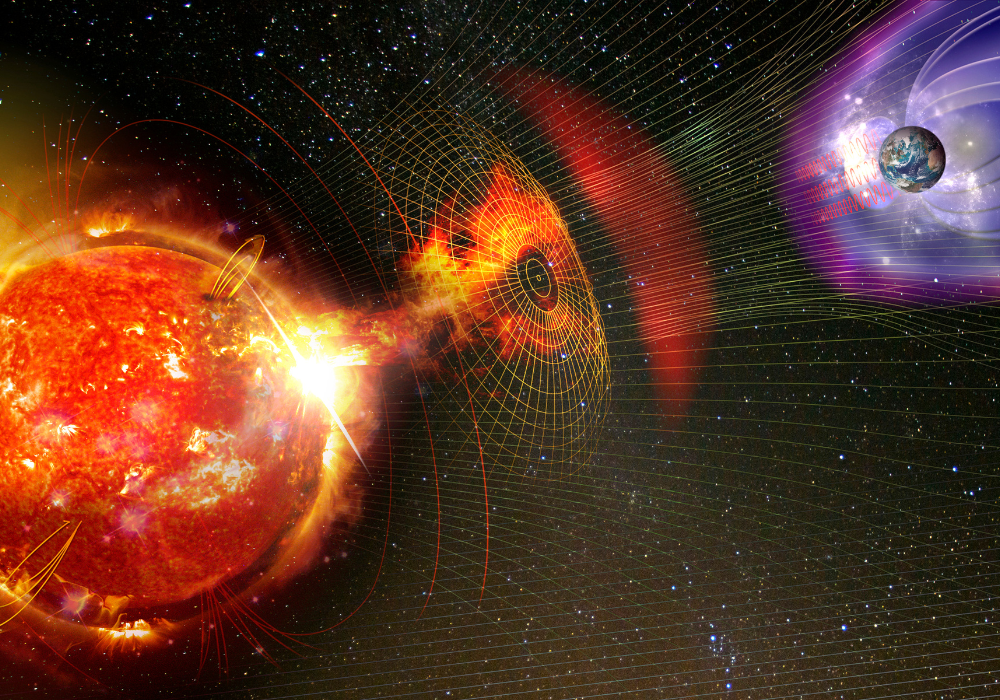

3. Earth’s atmosphere was bombarded by solar storms.

Without a strong magnetic field to redirect charged solar particles, Earth’s upper atmosphere took a direct hit from solar storms. Scientists studying ice cores and sediment records found spikes in radioactive isotopes like beryllium-10 and carbon-14—clear signs of intensified cosmic radiation. These bombardments likely caused the atmosphere to ionize, triggering electrical disruptions and possibly even climate anomalies. In today’s world, such exposure would devastate power grids, GPS, and satellites.

Back then, it could have disrupted atmospheric circulation patterns, altered rainfall, and weakened the ozone layer. The skies themselves may have looked strange—brighter auroras in unusual places, and eerie glows not typically seen at mid-latitudes.

4. Auroras lit up the skies near the equator.

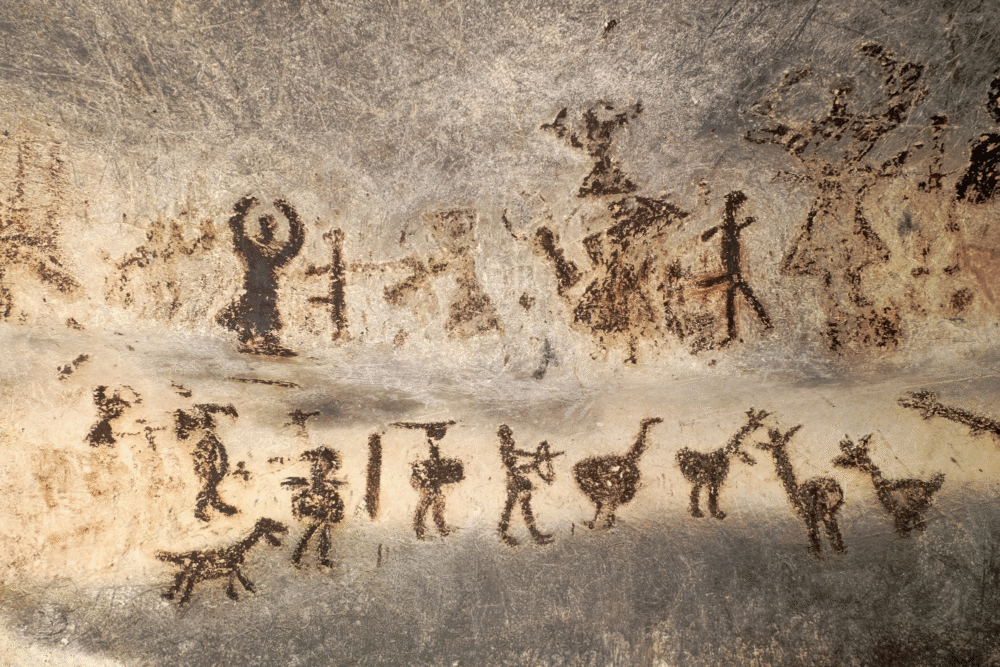

Normally, auroras are confined to high latitudes, where the magnetic field guides solar particles toward the poles. But during the Laschamps Excursion, with Earth’s magnetic shield drastically weakened and distorted, auroras likely appeared in places they don’t belong—like equatorial Africa or central Australia. Ancient humans would’ve seen glowing skies and flickering lights unlike anything in their usual experience.

This sudden celestial activity might have sparked fear, myth, or even religious interpretations. Researchers speculate that such events may be recorded in early cave art or oral traditions. These light shows, though beautiful, were signs of the invisible turmoil Earth was enduring above our heads.

5. Climate chaos followed the magnetic field collapse.

The weakening of the magnetic field didn’t just let in more radiation—it may have also destabilized the global climate. Some studies link the Laschamps Excursion with sudden cooling events and altered rainfall patterns. In parts of the Southern Hemisphere, the climate shifted rapidly, bringing droughts or temperature drops that impacted vegetation, animal populations, and early human settlements.

The collapse may have contributed to massive climate stress right when humans were beginning to migrate and adapt. While scientists debate whether the magnetic collapse directly caused climate change or just intensified other forces, there’s growing consensus that it played a role in tipping the atmosphere into chaos.

6. Ozone layer depletion endangered surface life.

Cosmic and solar radiation unleashed during the collapse is believed to have significantly damaged Earth’s ozone layer. The ozone layer absorbs harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun, acting as another crucial shield. Without it, UV rays would have scorched the surface, increasing mutation rates in plants, animals, and humans.

Some scientists suggest that the Laschamps Excursion temporarily thinned the ozone to dangerous levels, forcing life to seek shelter—either underground, underwater, or in denser forests. UV exposure may have also influenced the evolution of skin pigmentation or behavior. It’s another example of how one planetary shift can cascade through nearly every living system on Earth.

7. Human evolution may have been affected.

Some researchers speculate that the intense environmental changes caused by the magnetic collapse could have influenced human evolution and migration. Evidence from Australia and Europe shows shifts in population density and settlement patterns right around the Laschamps timeline. It’s possible that radiation exposure pushed early humans to adapt new survival strategies—like living in caves, changing diet, or moving to more hospitable regions.

There’s even debate about whether the event played a role in the disappearance of Neanderthals, who were already facing pressures from climate and competition. If true, the collapse of Earth’s magnetic field may have helped reshape the very path of our species.

8. Mass extinctions may be linked to the collapse.

While the Laschamps Excursion didn’t wipe out all life, some researchers believe it contributed to a wave of extinctions among large mammals and megafauna. As environmental stressors piled up—UV radiation, climate shifts, and ecosystem disruption—certain species couldn’t adapt quickly enough. In Australia, for instance, several giant animal species disappeared around this time.

Though other factors like human hunting and existing climate trends played roles, the magnetic collapse may have been the tipping point. The lesson is sobering: even a relatively short-lived geomagnetic event can ripple across the globe, changing evolutionary trajectories and erasing entire lineages in its wake.

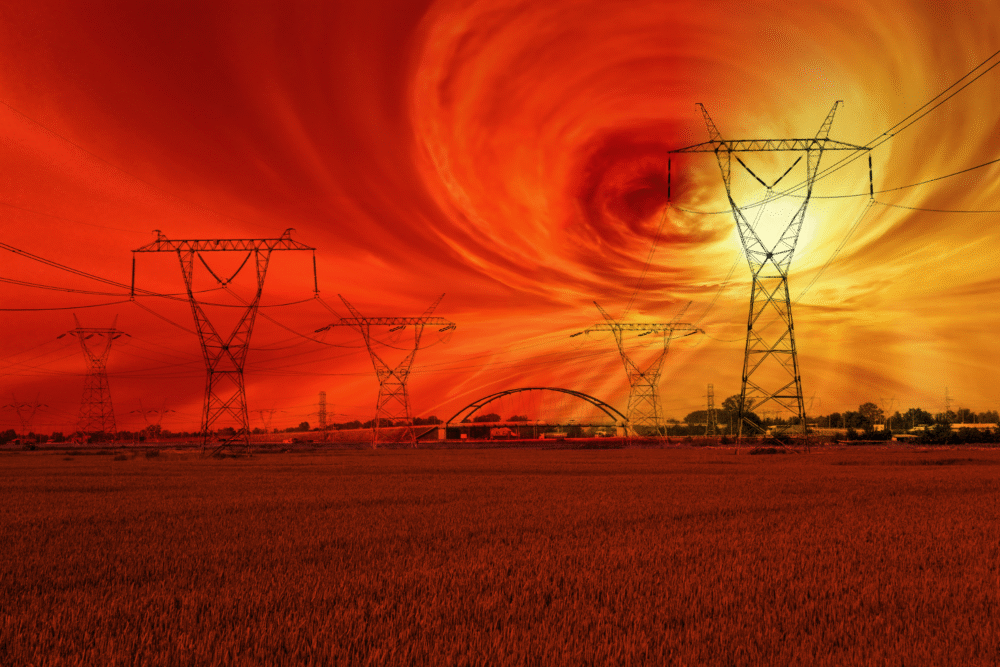

9. The collapse reveals how vulnerable we still are.

Perhaps the most unsettling part of the Laschamps Excursion is the reminder that Earth’s magnetic field can weaken or reverse again. In fact, some studies suggest the field has been gradually weakening over the last 200 years. If a similar event occurred today, the consequences would be staggering: fried satellites, collapsed electrical grids, disrupted navigation, and dangerous radiation exposure.

Our world—far more dependent on electronics and infrastructure than that of early humans—would be especially fragile. Understanding what happened 41,000 years ago isn’t just a history lesson. It’s a warning sign that our planet’s core can still turn the tables on us.

10. Geologic records give us the only clues.

Because there were no written records 41,000 years ago, scientists rely on geologic clues to piece together what happened during the magnetic collapse. Ice cores, ocean sediments, lava flows, and tree rings hold chemical signatures of the Laschamps Excursion.

By analyzing spikes in certain isotopes and comparing them across continents, researchers can reconstruct the sequence and timing of events. These clues also help refine our understanding of how fast magnetic reversals can occur and what side effects they bring. It’s a forensic investigation on a planetary scale, and every new discovery brings fresh insight into how our planet has behaved—and how it might again.

11. We’re still unsure how close we are to another collapse.

Despite advances in geophysics, we still don’t fully understand when—or if—another magnetic reversal might happen. The South Atlantic Anomaly, a weak spot in Earth’s magnetic field, has been growing over the past century, raising concerns about global field stability. Some scientists believe it could be a sign that another excursion or full reversal is in the works, possibly within the next few thousand years. Others argue it’s just a normal fluctuation.

Either way, the Laschamps Excursion proves that such collapses have happened before—and could happen again. The big question now is whether we’ll be ready when the magnetic field begins to fall apart once more.