Most people trust expiration dates blindly—and it’s costing us billions in food.

We’ve all done it—pulled a yogurt from the fridge, spotted the expiration date, and tossed it without even a sniff. But those small printed dates, meant to offer peace of mind, are actually a major driver of food waste. In the U.S. alone, millions of tons of perfectly edible food end up in landfills every year, much of it tossed out due to confusing or overly cautious expiration labels. The truth? Most dates aren’t about safety—they’re about quality, branding, and liability. Here’s how these misleading labels quietly contribute to one of the biggest waste problems we face today.

1. People assume “expired” means dangerous, even when it doesn’t.

The biggest misconception is that once something passes its printed date, it becomes unsafe to eat. But most dates—like “best by,” “sell by,” and “use by”—aren’t regulated or based on food safety. They’re about peak quality, not spoilage. So tossing food that’s a day or two past its date is often completely unnecessary.

Yogurt, eggs, dry goods, and even milk can be fine well after the stamp fades. Our over-reliance on these arbitrary dates makes us ignore actual signs of spoilage and waste food that’s still perfectly good.

2. Manufacturers set dates to protect their brand—not you.

Expiration dates are often chosen by food producers to reflect when the product will taste best—not when it goes bad. They’re covering their reputation, not your health. If crackers go a little stale or cereal loses crunch, they’d rather you buy fresh than risk a subpar snack and blame them.

This self-serving approach makes consumers think food “expires” faster than it does. So while that granola bar may taste slightly off-texture at month five, it’s not going to hurt you. But by then, many people have already tossed it.

3. Stores throw away massive amounts of food before the date.

Retailers don’t wait for food to actually go bad. To keep shelves looking fresh, they often pull items days—or even weeks—before the printed date. This preemptive purge leads to tons of food waste behind the scenes. Deli meats, produce, dairy, and baked goods are some of the biggest victims. Many of these items are donated, but much still ends up trashed.

Why? It’s cheaper and safer for stores to dump it than deal with a customer complaint or legal risk. The loss gets passed along in the form of higher prices.

4. “Best by” and “sell by” dates confuse nearly everyone.

Let’s be honest—no one knows what these terms actually mean. Are you supposed to eat it before then? Buy it before then? Toss it after that day? It varies depending on the product and brand, and there’s no national standard. This confusion leads to panic-purging fridges and pantries.

One survey found that nearly half of people throw out food on or before the “best by” date, even though it’s still good. The labels are meant as rough guidelines, not expiration mandates—but most of us were never told that.

5. “Use by” labels sound final—but often aren’t.

“Use by” carries the most urgency, but unless it’s on infant formula, it’s not enforced by law. It’s just a suggestion from the manufacturer, and doesn’t mean the food becomes toxic at 12:01 a.m. the next day. Bread, canned goods, and frozen meals with a “use by” label can still be eaten if stored properly.

But people read that phrase and immediately think of mold or food poisoning. The wording is misleading, and manufacturers know it triggers consumers to buy more—and waste more.

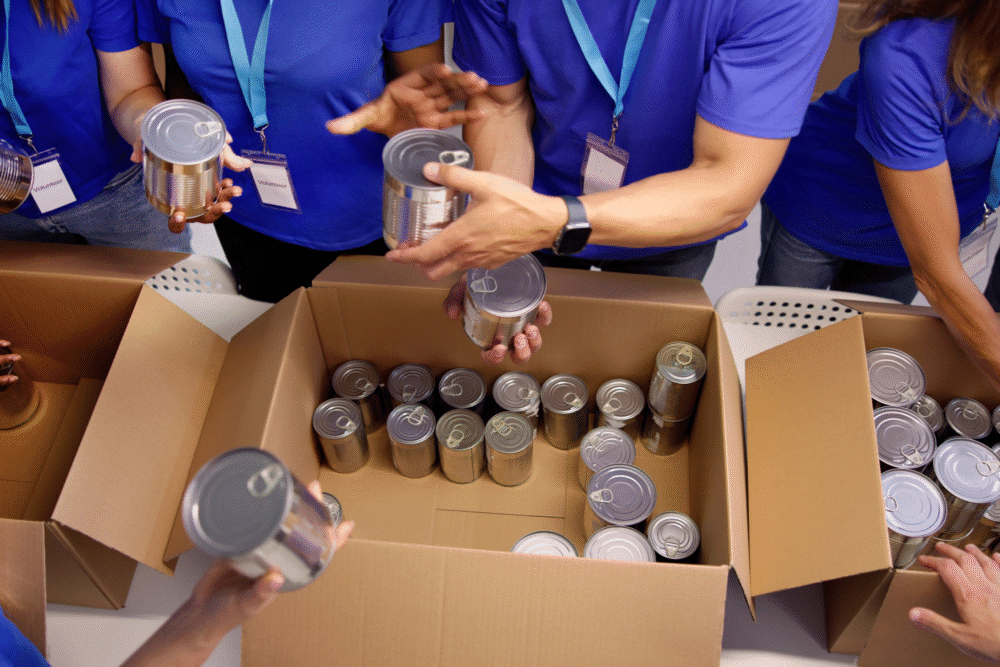

6. Perfectly edible food gets dumped from food banks, too.

Even organizations trying to fight hunger often follow these confusing expiration dates. Some food banks, to avoid liability or confusion, won’t distribute items close to or past their printed dates—even though the food is safe. That means tons of donations from stores, warehouses, and private donors end up in dumpsters instead of in the hands of families who need them.

A few progressive food rescue groups are challenging this by educating people on real spoilage signs, but the damage is widespread and deeply ingrained.

7. People toss expensive health foods too soon out of caution.

Organic snacks, plant-based milks, and pricey superfoods come with short shelf lives—or so we’re led to believe. Because consumers are especially cautious with “healthy” foods, they’re more likely to discard items just days past the date. This caution leads to guilt-driven waste, especially when you’ve paid a premium for the item.

But those chia seeds, green powders, or almond milk cartons may last weeks or months longer than you think. Check them with your eyes and nose, not just the date stamped on the bottom.

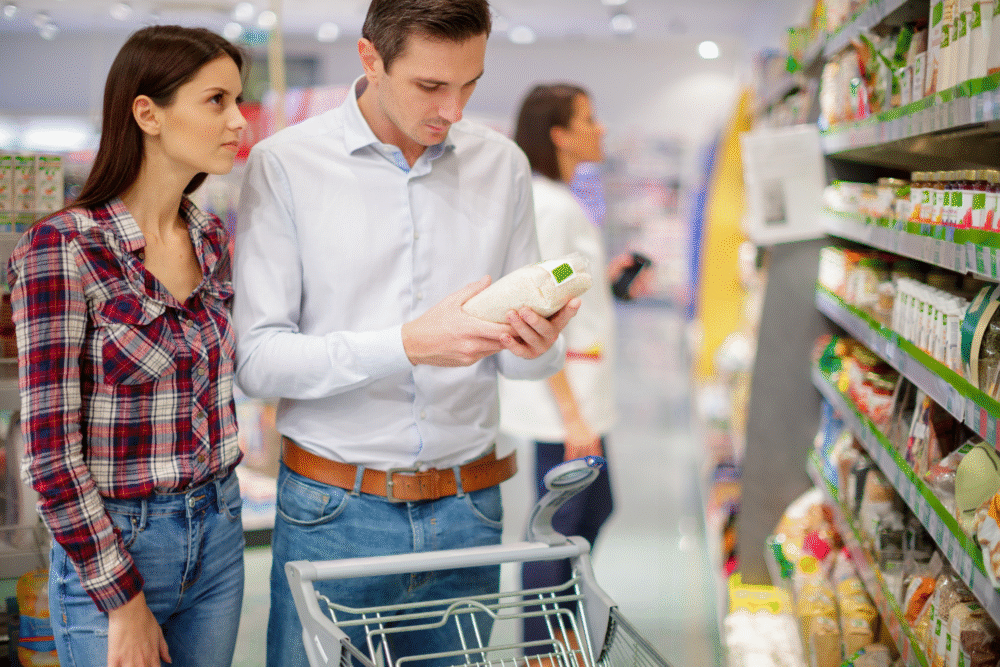

8. Bulk shoppers toss more food than they save.

Stocking up at warehouse clubs or during sales feels smart—until half the pantry is expired before you can finish it. Buying in bulk only saves money if you actually use it. With larger quantities comes more pressure to consume quickly, and many families end up dumping bags of rice, snacks, or frozen food after misreading dates.

The convenience becomes costly when expiration paranoia kicks in. Instead of rotating stock or freezing extras, people chuck unopened goods that are still edible, thinking they’ve gone “bad.”

9. Fridge clutter causes good food to quietly expire.

A packed fridge hides expiration dates and pushes items to the back, where they’re forgotten. Weeks later, you find that half-eaten hummus or tub of sour cream, glance at the date, and toss it—without checking if it’s still okay.

The chaos of modern refrigeration means perfectly good food gets ignored until a date gives you an excuse to dump it. Better organization, clear containers, and visual checks could drastically reduce waste, but instead, we let those printed numbers guide the toss.

10. Fear of judgment keeps people from sharing older food.

You may know that loaf of banana bread is still good or that canned soup is fine for months to come—but offer it to someone else, and you’ll feel embarrassed. We’re trained to treat “expired” food as dirty or shameful, even when it’s not. This stigma prevents food-sharing, neighborhood swaps, or even giving leftovers to friends.

If we normalized checking food with our senses instead of shaming anything past its prime, less would be wasted. But right now, a date stamp carries more weight than common sense.