Objects we overlook today once carried prayers, rituals, and power.

It’s easy to forget how much meaning an object can hold when we’re surrounded by mass production and endless duplicates. But throughout history, the most ordinary tools and materials weren’t just functional—they were sacred. Their shapes, uses, or origins linked them to something larger: cycles of nature, stories of creation, ancestral memory. These weren’t just symbols; they were living parts of ritual and reverence.

Over time, as belief systems shifted and modern life sped up, much of that symbolism faded. What once carried protection, fertility, or divine connection now fills junk drawers or sits on shelves unnoticed. Yet in old stories, regional traditions, and archaeological finds, those meanings still flicker. From salt to mirrors to thread, the sacred has long lived in places we now ignore. Rediscovering that history doesn’t mean we have to return to the past—but it can shift how we see the things we touch every day.

1. Salt was once worth more than gold—and used to bless, cleanse, and protect.

In ancient Rome, soldiers were sometimes paid in salt, a practice that gave us the word “salary.” But salt’s value wasn’t only economic. Writers at Ilanga Nature note that in many cultures, salt was believed to ward off evil, purify the environment, and serve as a spiritual shield. Sprinkled at thresholds, poured into fire, or buried under doorways, salt was believed to hold cleansing power that connected the physical and spiritual worlds.

That symbolism lasted for centuries. In Japanese Shinto tradition, salt is still scattered at the entrance to temples and used in sumo wrestling for purification. In parts of Eastern Europe and the Middle East, bread and salt are offered as a gesture of welcome and blessing. Today, we use it to season food without a second thought. But its ancient role as both currency and consecration reminds us that survival and spirituality once lived side by side—in a single grain.

2. Bread wasn’t just food—it symbolized life, offering, and sacred connection.

Bread has long been a symbol of sustenance, but also of the divine. Claudine Cassar writes on Anthropology Review that in ancient Egypt, bread was a core funerary offering meant to nourish the deceased and connect the living to the afterlife.

In Christian tradition, bread became the body of Christ. In Slavic cultures, a round loaf was presented during weddings and funerals, accompanied by salt to signify the eternal bond between people and the earth.

The process of making bread—grinding grain, kneading dough, waiting for it to rise—was itself seen as a kind of alchemy. It turned raw material into nourishment, and often, into a sacred gesture. Sharing bread meant sharing life. That symbolism still lingers today in phrases like “breaking bread” or in ceremonial challah during Shabbat. While modern loaves come pre-sliced and wrapped in plastic, bread’s history as a spiritual offering stretches back thousands of years.

3. Mirrors once revealed more than reflections—they were portals and protectors.

Long before mirrors were mass-produced, polished metal or water-filled bowls served as reflective surfaces used in divination. In ancient Greece and Rome, people believed mirrors could capture the soul or reveal hidden truths. In parts of China and India, mirrors were hung to repel evil spirits, reflecting negativity back toward its source.

Savannah R. Reeves explains on the Molly Brown House Museum site that Victorians often draped mirrors after a death to keep the spirit from becoming trapped or lost within the glass. In some Indigenous and African traditions, mirrors still play a role in rituals meant to connect with ancestors or see beyond the visible world. Today, we check our hair or take selfies without thinking about it. But the act of seeing one’s own reflection was once an intimate and mysterious experience—one tied to power, vulnerability, and the unseen.

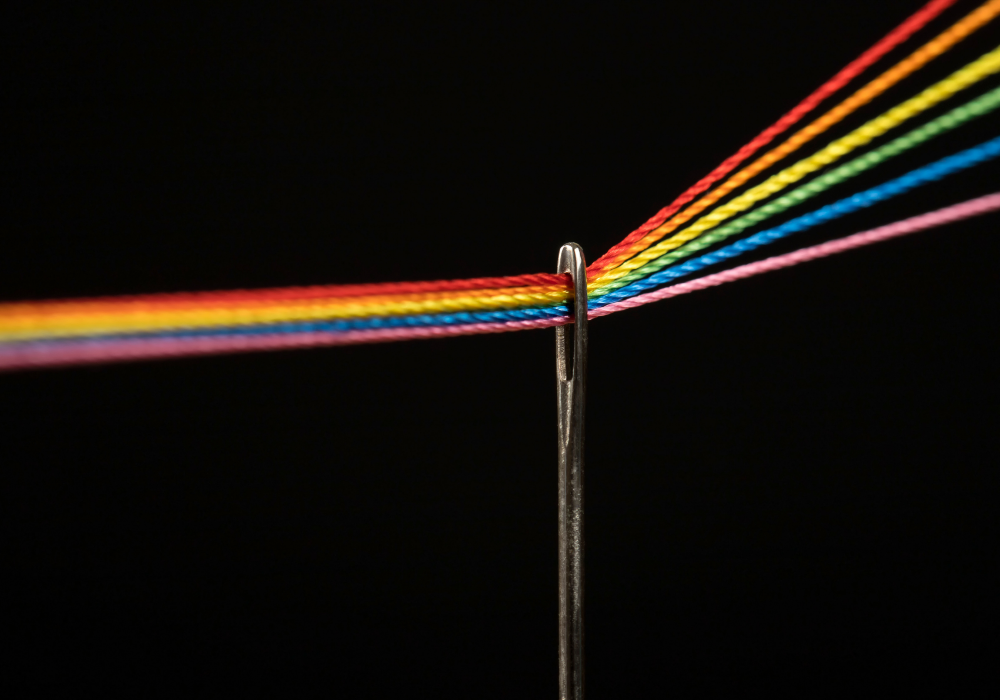

4. Needles and thread were used in rites of protection and cosmic balance.

Across cultures, sewing and weaving were never just chores. In Greek mythology, the Moirai—or Fates—spun, measured, and cut the thread of life itself. In Andean traditions, weaving patterns mirrored the cosmos and told stories passed down through generations. In Jewish mysticism, red threads were tied around wrists to ward off the evil eye. Needles, too, had symbolic weight. Some African and Native American cultures used them in ritual piercing or to sew protective garments imbued with prayers.

Thread wasn’t just a material—it was a line between worlds, holding things together in both the literal and spiritual sense. Now, we patch a hole or hem a sleeve without ceremony. But for centuries, the tools of fabric-making carried sacred resonance, connecting human hands to myth, memory, and the divine.

5. Brooms swept more than dust—they were tools of ritual and rebirth.

In many folk traditions, brooms weren’t just for cleaning—they marked transitions, offered protection, and symbolized thresholds between worlds. In parts of West Africa and later in African American culture, couples “jumped the broom” during weddings to honor ancestral rituals and signify the crossing into a new life together. In European folklore, brooms were used in spring rituals to “sweep out” the stale energy of winter.

Witches, real or accused, were said to fly on broomsticks not because of superstition alone, but because the broom was already tied to magical practices in agricultural cycles and hearth rituals. Hanging a broom by the door was believed to keep unwanted spirits out. Today, we stash them in closets or lean them in corners—but in centuries past, brooms were part of life’s big transitions. Their symbolism lived in the space between the ordinary and the sacred.

6. Bells once summoned spirits, banished storms, and marked sacred time.

The sound of a bell wasn’t just a signal—it was a threshold. In Buddhist temples, bells were rung to clear the mind and call attention to the present moment. In medieval Europe, church bells marked not only the hour but also warded off lightning and plague, their tones believed to disrupt malevolent forces. Farmers rang bells to guide the spirits of crops and herds. Small bells were often tied to clothing or doorways for protection. In some cultures, the soft ringing was thought to confuse or repel harmful spirits.

While today we mostly hear bells in schools or on holiday decorations, they were once instruments of awe—marking beginnings, endings, and moments when the physical and spiritual worlds overlapped. Their sound still carries a subtle weight, even if we’ve forgotten why.

7. Ashes weren’t just waste—they were sacred symbols of mortality and renewal.

In many cultures, ash represents what remains after transformation. In Hindu rituals, sacred ash—vibhuti—is applied to the forehead as a symbol of purity and impermanence. Ashes from burned herbs or offerings were used in Celtic and Slavic rites for protection, blessing, or divination. Even in Christianity, Ash Wednesday reminds the faithful of life’s fragility: “from dust you came and to dust you shall return.”

Fire itself was sacred, and what it left behind wasn’t discarded lightly. Ashes were sometimes mixed into fields to bless crops or spread around homes to protect against illness. While today we often sweep them away without thought, ashes once carried meaning well beyond the fire—tracing the thin line between life, death, and rebirth.

8. Stones were used to anchor prayers, honor ancestors, and hold memory.

Stones have long been more than landscape. In Indigenous traditions across the Americas, certain rocks were believed to be sentient, carrying wisdom from the Earth. Cairns in Scotland and Ireland marked graves or sacred sites, while in Jewish practice, placing a stone on a headstone honors the dead and keeps memory grounded.

Some cultures used stones as talismans, choosing them for shape, color, or origin. Others built stone circles or carved petroglyphs to map cosmology and story.

Even smooth river pebbles held meaning—tokens of protection, luck, or balance. Today, rocks might just line our driveways or gather dust on shelves, but for much of human history, they were seen as the bones of the Earth—still, quiet, and profoundly alive.

9. Water vessels once held more than liquid—they carried life, purity, and ritual.

Clay pots, jugs, and bowls were often made with care not just for function, but for ceremony. In Hindu households, kalash vessels filled with water and mango leaves mark the presence of the divine. In Christian traditions, holy water fonts at church entrances offer spiritual cleansing. In pre-Columbian cultures, vessels buried with the dead symbolized passage to the afterlife.

The act of carrying or pouring water was often sacred. It mirrored rain cycles, fertility, and the role of women as stewards of life. Water vessels also appeared in birth and death rituals, underscoring their symbolic role in beginnings and endings. Today’s plastic pitchers and metal bottles feel disposable—but the long legacy of water vessels reminds us that some containers were once meant to carry more than just hydration.

10. Hair was braided, cut, or kept in ritual as a link to spirit and story.

Hair has been imbued with power across countless cultures. In some Native American tribes, hair is considered an extension of the soul, cut only during mourning. In Sikhism, uncut hair is a symbol of respect for the body’s divine form.

In Victorian times, locks of hair were woven into mourning jewelry, preserving a piece of someone lost. Hair has also marked rites of passage—braided for ceremony, shaved for purification, or burned to release emotion. Even today, some people bury or save cut hair rather than toss it away, honoring a lingering belief in its energetic weight. While most of us don’t think twice about hair trimmed at a salon, its symbolic role has quietly persisted through time, a thread connecting body and spirit.

11. Clay wasn’t just for shaping—it was a medium between earth and breath.

Before it became the stuff of hobby pottery, clay held deep cosmological meaning. Many origin stories—from Mesopotamia to the Americas—describe humans being shaped from clay or earth, animated by divine breath. Clay jars held sacred oil or wine; clay tablets recorded prayers. It was both canvas and container, humble yet holy.

In West African traditions, clay is used to build shrines and homes, blending the sacred with the everyday. In Andean communities, clay figurines represented spirits of nature or ancestors. Its malleability echoed themes of birth, growth, and change. Working with clay was a form of creation, reflection, and, often, reverence. Today, we may see it as a simple material—but for millennia, it was a bridge between human hands and the divine.